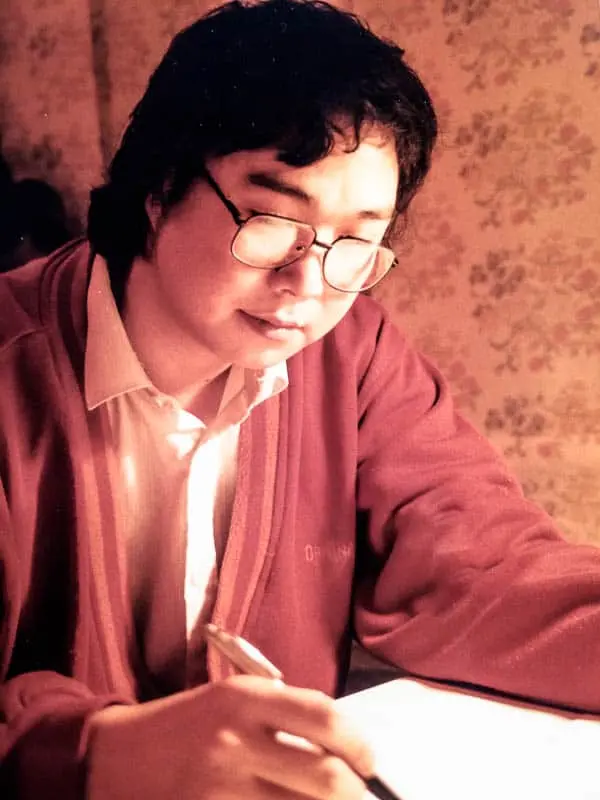

“Since when did love become a crime?” Chinese writer Liao Yiwu asks himself—and asks us—this question as he relates his recent conversations with detained Chinese poet, Liu Xia. Over the past two months, Liao has released two audio recordings of his phone conversations with Liu Xia in an effort to push for her freedom. Both essays were originally posted on ChinaChange.org, an important website for those following human rights and civil society developments in China.

Liu Xia has been under house arrest for the past eight years, forced to live a life of solitude for the “crime” of being the widow of one of China’s most famous dissidents. In this essay, Liao Yiwu pairs his updates on Liu Xia’s situation with his own sorrow and fury at the torment his friend is going through. “This is enough to make one burn with rage,” he writes at one point. At another point, simply: “More sobbing. Endless sobbing.”

Last month, PEN America and Amnesty International launched a series of videos featuring celebrated literary figures and artists reading Liu Xia’s poetry and calling for Liu Xia’s freedom. We continue to call for her freedom today. We take as our guiding maxim Liu Xia’s own words, shouted from a car window in 2013 on one of her few permitted moments in the public eye: “If they tell you I am free, tell them I am not free.”

Read this essay. Listen to Liu Xia’s voice. And then join people of conscience everywhere in calling for Liu Xia’s freedom. You can send a message to the Chinese government through our coalition partner Amnesty International, or repost this article on social media using the hashtag #FreeLiuXia.

Liao Yiwu writes: Dear friends, I am hereby once again publicizing a portion of a conversation with Liu Xia (劉霞), this time on May 25, 2018. The recording runs 21 minutes; I have excerpted the final 8 minutes. Liu Xia said: “Loving Liu Xiaobo is a crime, for which I’ve received a life sentence.”

This is enough to make one burn with rage. Since when did love become a crime? When Xi Jinping’s father was labeled an anti-CCP element and jailed by Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution, his mother didn’t abandon him, and nor did she get locked up for years like Liu Xia has.

In January 2014, by which point Liu Xia had been cut off from the world for more than three years, I was finally able to reach her from Germany by telephone at her home in Beijing. As soon as I spoke her name, she began to sob, and she went on sobbing for 20 minutes. I didn’t know what to say. She hung up. I called back. It was the same—she’d almost become speechless.

In the blink of an eye more years have elapsed—the torment of it impossible to put in a few words. In the end, it came to this: Xiaobo was murdered under the cover of “bail on medical grounds.” The couple were able to see each other in the prison-like hospital ward for less than a month. Every day, there were people in and out the ward, over 100 times in all, “rescuing” Xiaobo while sealing him off from the outside world.

Xiaobo desperately wanted Liu Xia to leave China, and even dreamt of accompanying her and Liu Hui, Liu Xia’s brother, to Germany in the little time left in his life. After he died, the Chinese police said to Liu Xia many times that as long as she cooperated with them, they’d let her leave the country to seek treatment.

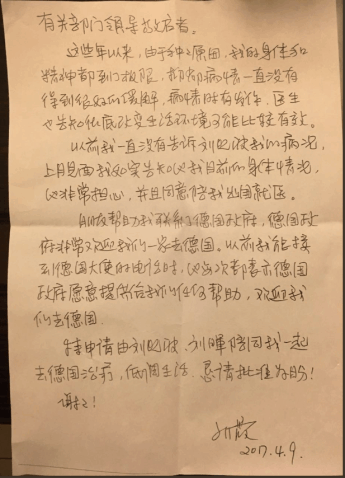

In April 2017, I went through a contact—one of the most famous poets and singers of the Berlin Wall era, Wolf Biermann, as well as his wife—to reach out to Chancellor Angela Merkel with a letter asking for help. I attached a handwritten note by Liu Xia, titled “Application for Exiting China Submitted to Relevant Departments” (dated April 9, 2017). My letter was met with a quick response, and a communication channel with the Chancellor was established. By now, the German and Chinese governments have been engaged in private negotiations for well over a year already. In early April of this year, in response to numerous apparently optimistic signals, Liu Xia packed, and packed again, getting ready to travel—but her dreams dimmed and went dark. The Chinese official who had made promises to her had disappeared, and in despair Liu Xia declared that she would “use death to defy.”

I told her not to do anything rash, and sensing that things were reaching a crisis point, I published for the first time an audio recording of part of our conversation, with the headline “‘Dona, Dona,’ Give Freedom to Liu Xia.” The purpose was to turn a low-key negotiation into a loud call for the attention of the international community.

On the eve of May 24, before Merkel went to China for visit, I received a call from German’s public broadcaster, ZDF, where I made the earnest request that Chancellor Merkel bring Liu Xia out of China with her. I said that if this is impossible, she could at the very least express the wish to pay a visit to an ill Liu Xia or have a medical expert attend to her. For Liu Xia, trapped in her home-prison, this may have been her best opportunity to be freed.

And yet none of this came to pass! However, Merkel did meet with Li Wenzu, the wife of detained rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang, and other family members of the 709 victims in the German embassy in Beijing, and emphasized that she wished to personally meet with Liu Xia. When Merkel and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang held a joint press conference, Li announced that China respects humanitarian requests and was willing to engage in dialogue with Germany on “individual human rights cases”—this was the highest official statement on the matter.

As for Liu Xia, several days before Merkel’s visit, police entered her apartment and commanded her to leave the city on “travel.” Liu Xia staunchly refused, and the police didn’t force it. Instead, they tried to persuade her, again and again, and said that soon there would be someone coming to speak with her about leaving the country.

I’ve lost count of how many times this promise has been made. The police said that in July, after the first anniversary of Xiaobo’s death, she’d absolutely be allowed to leave China. I made clear my doubts, and advised Liu Xia to consider countermeasures beforehand in case they don’t let her go in July. Upon these words of mine, Liu Xia was terrified and sunk into a bout of despair.

The following is an excerpt of our telephone conversation on May 25, the last day of Merkel’s visit to China:

Liao Yiwu: When you kept saying “death death death” last time, I felt like I’d been hit with a jolt of electricity.

Liu Xia: When I’m dead, I won’t be a bother to anyone.

LYW: How can you say that? How can you die like that? This is not an option.

LX: So just keep me company, staying with me quietly. When you all tell me to do this and do that, I won’t take anyone’s calls anymore . . . You imagine these things are easy to do—if I can live like a free person, why do I even want to leave China? Xiaobo wanted me to go abroad to be free . . . because he had seen that police followed me everywhere and the room was fitted out with all sorts of surveillance equipment and nothing is easy for me to do. I’ve got a lot of friends here too . . . sometimes I’m so squeezed that I’m left with no choice . . .

LYW: Yes, you told me to record it last time—I felt you were falling apart. At that time, I . . .

LX: It’s no problem. But don’t ask me, as you did later, to do this or to do that . . .

LYW: OK, OK, OK. Just wait for July and see what they say.

LX: Right.

LYW: I feel that you’ll be able to get out eventually . . . but, it’s such a fucking torment . . .

More sobbing. Endless sobbing. I could neither stop her nor comfort her. So I started playing the song “Too Much Love” by Israeli singer, Motty Steinmetz. I had played it for her many times; she liked it a lot. Steinmetz had learned traditional Jewish hymns from his grandfather since childhood, and his lyrics are drawn from the Hebrew Bible.

As the song played, Liu Xia wailed: “They’re going to keep me here to serve out Xiaobo’s sentence.”

I was flabbergasted. Last year when she finally returned home after Xiaobo’s death, she cast her gaze around a room full of books. The old ones he’d read; the new he’d never get to. She felt suffocated and reached out for her medication when she collapsed onto the floor. When she came to a few hours later, she found herself bruised all over.

As I considered all this, words from Jeremiah sprung from the depths of my mind:

“Thus saith the LORD;

I remember thee,

the kindness of thy youth,

the love of thine espousals,

when thou wentest after me in the wilderness,

in a land that was not sown.”

This seemed like the voice of Xiaobo from Heaven. Liu Xia continued: “I want to see just how much more cruel they can get and how much more shameless they’ll become; I want to see how much more depraved this world is.”

I responded: “All you have ever done is love, for all you’ve gone through . . .”

She said: “They should add a line to the constitution: ‘Loving Liu Xiaobo is a serious crime, a life sentence.’”

I was too struck by these words of hers to continue. Liu Xia said: “I’m going to go take my medication.”

I bid her goodbye: “Be patient. Let’s wait until July.”

She ‘hmmmed’ and hung up. I sat still at my desk for a long while. The 29th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre is approaching, and I decided to send out this message to the world, continuing to call for her to be freed.

Dear friends, whether you’re a foreigner or Chinese; whether you’re a political leader, a parliamentarian, a diplomat, or a regular citizen—friends of Xiaobo who are dissidents, poets, authors, academics, artists, sinologists, journalists, actors, lawyers, and public intellectuals—if you’re in Beijing, please take a moment of your time to go and visit Liu Xia. If you’re concerned to go by yourself, bring a few like-minded friends along. If they don’t let you see her, please read a poem outside her apartment building or call out to her. If her minders stop you, give them a flyer with her poem on it.

If you’re not in Beijing, or not willing to do the above, at least forward around the recording. Have more people—including U.S. President Donald Trump, French President Emmanuel Macron, British Prime Minister Theresa May, and the Nobel Committee in Norway—understand what the wife of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo has been going through for all these years.