I tried writing in the county jail, but it was too intense. The events that had landed me there, the ones I was trying to write about, were much too fresh. Plus, we only went outdoors twice during the eleven months I spent awaiting trial and sentencing—the latter a foregone conclusion, as the state of Michigan has mandatory sentences and mine was Life Without the Possibility of Parole, basically a death sentence for states without the chutzpah to actually inject that lethal cocktail of drugs.

I tried to write, but couldn’t. Instead I had debilitating panic attacks where my heart would beat wildly and I would hyperventilate, spending all day, every day in a 10×10 cube with three, sometimes four, others. I was finally put on my own cocktail of drugs: Trazodone, Depakote, Seroquel, and Paxil. Thankfully, the panic vanished, but a side effect was shaky hands–the writing looked like a toddler’s. I read constantly, though, keeping the books stationary, splayed open on my knees, the ones I’d said I would read if only I had the time: War and Peace, Ulysses, Infinite Jest, the oeuvres of Virginia Woolf, and William Faulkner.

I must have been writing in my mind because the first day in quarantine—a 4 to 6 week period where the new inmate is tested physically and mentally to see where he might fit in and what programs might benefit him—a sentence kept repeating itself, and not the one I’d heard the judge proclaim: “Sicilian Joe was a saucier until a Cadillac hit him doing sixty and knocked the recipes out of his head.”

I still wonder where this came from. Sicilian Joe, an apparent amalgam of those I’d known over the past several months, showed up fully-formed in a twelve page story called “County.” Six weeks later, when I was no longer so heavily medicated, the story was written in longhand. I read it aloud to my first bunky, a twenty-five-year-old kid named Ryan who had shaken his infant son to death. Ryan didn’t like the ending. He said he wanted something more concrete, exact, less “shady.” I knew that I’d nailed it. It was a good story, one I could never get published, in even the smallest literary journal. I probably sent it to twenty.

I used to save my rejection slips. At one point I counted 100. If writing is mysterious, publishing is its freakish, maddening, passive-aggressive, cousin. Those rejection slips (I still get hard copies) seem to come only on the days already full of maudlin ennui.

A man I’m still friends with today, Jarrett Haley, read a couple of my flash fictions in Hobart and asked if I had other writings. I had, and over the next couple of years I published several short stories and wrote over a hundred book reviews for Jarrett’s literary journal, BULL. He was the first editor of The Graybar Hotel, back before it had a title. We worked on one story at a time, run through an Apple program (not this prisoner’s area of expertise, so take all computing talk with a grain of salt) that allows the user to highlight questions in what look to be thought-bubbles. I would send back revisions via snail mail. From my end, it worked seamlessly and easily.

Jarrett was a great editor, and thought the stories deserved to be published in book form. I would never have dared suggest such a thing. There is so much rejection in the arts that it becomes hard to expect good things to happen. That may also be part of my personality, but Jarrett found an agent near him, Sandra Dijkstra in San Diego, who had the book sold to Scribner over a weekend for an advance of $150,000—a number that would come back to haunt me.

I know that Jarrett was a great editor because an actual editor told me she didn’t have much to do before the stories went to press. The ones she did make minor adjustments to were revised via JPay (the prison version of email). We would also speak weekly by phone—she in her office in 30 Rockefeller Plaza, and me in a prison in Coldwater, Michigan.

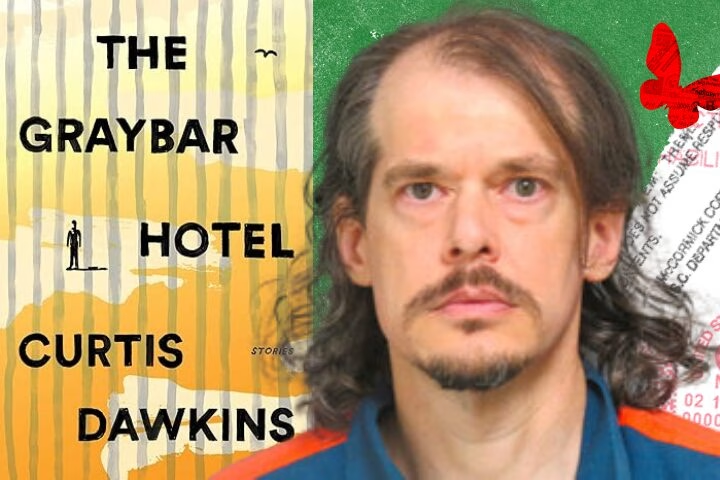

The hardcover edition of The Graybar Hotel came out on July 4, 2017, simultaneously to a New York Times article about me and the book. I did, over the next few months, several in-person interviews and in one of them, to The Detroit News, I gave the amount of the advance for the book. I cannot regret this. What introvert doesn’t love attention? This one does! He likes to talk and talk about himself. BUT writers should write, not talk.

Interviews are fun, though mine are heavily tinged with the crime I committed. A man is dead. I did not know him, but I killed him. I regret it and think about it every day. I was a reckless maniac that night, a deadly menace. His siblings have not hidden the fact that they hate me, that I should not even be alive, let alone have a book published. There was blowback, and though I had made it absolutely clear in the book’s acknowledgements that every penny I made from anything I ever wrote would go to my three precious children, the State of Michigan sued me roughly a year after the book came out.

There is a law in Michigan called the State Correctional Facility Reimbursement Act (SCFRA), which says the state treasurer, through the attorney general, can seek recompense for a prisoner’s room and board, up to 90% of any assets he/she has.

There is no way around the state getting a portion of these proceeds. None. SCFRA is a law. I suppose that I could have used a pen name, but this was my dream–a book with my name on it! I used to wander bookstores, hold books in my hand, and imagine my name there. That dream sent me back to college in 1995. If you told me today that had I put a pseudonym on the book I could get away without paying anything, I would not do it.

Another New York Times article followed, and this time also featured my partner, the novelist Kimberly Knutsen, mother of those three kids. We like to think that the bad press (she came across as a very sympathetic single mom) helped to keep the Republican candidate for governor, Bill Schutte–at that time the attorney general of Michigan–out of office. If we played even a tiny part, it was worth it.

They say there is no such thing as bad press, but an entire state suing an author might be the sole exception. Neither the publisher nor the agent showed any interest, from that point on, in publishing anything I wrote. So, though the attorney general said in their legal brief that their intent was “not to censor”–something I had not considered until the state brought it up–it seems exactly what they managed to do.

No one wants to be sued. If publishing is nearly impossible for free-world authors, it is exponentially harder for inmates, for many reasons. It is now probably harder thanks to Michigan and me. Book publishing is an extremely risk-averse business.

During all of this, I have never stopped writing. I paint as a hobby. I am a facilitator for a brand new writing club at my current prison, using PEN America’s indispensable The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison. My children are healthy, and I have an incredible 3-year-old grandson named Noah. I had a book published, The Graybar Hotel, that I’m very proud of, and I continue to write. I am one of the most blessed prisoners you’ll ever meet!

My agent and I parted ways a year ago. Like most other writers in prison, I am looking for a new one. I am back at the beginning.

Please understand that my case is not typical. Laws vary from state to state. In the end, the state has received less than $10,000 from my advance, most of which had already been paid out by the time the court proceedings had concluded. We have settled on 50% of all future earnings, though, so by suing me they might have unwittingly cost themselves.

The first thing I sought when coming to prison was a pencil and paper. I had that coming. It seems perfectly harmless. I have begun a memoir, though I’m calling it fiction. I am back at the beginning.

Curtis Dawkins authored the critically-acclaimed short story collection, The Graybar Hotel (Scribner, 2017), and has been published in Vice, The Hudson Review, Hobart, and Beloit Fiction Journal while incarcerated in Michigan’s semi-Arctic Upper Peninsula.