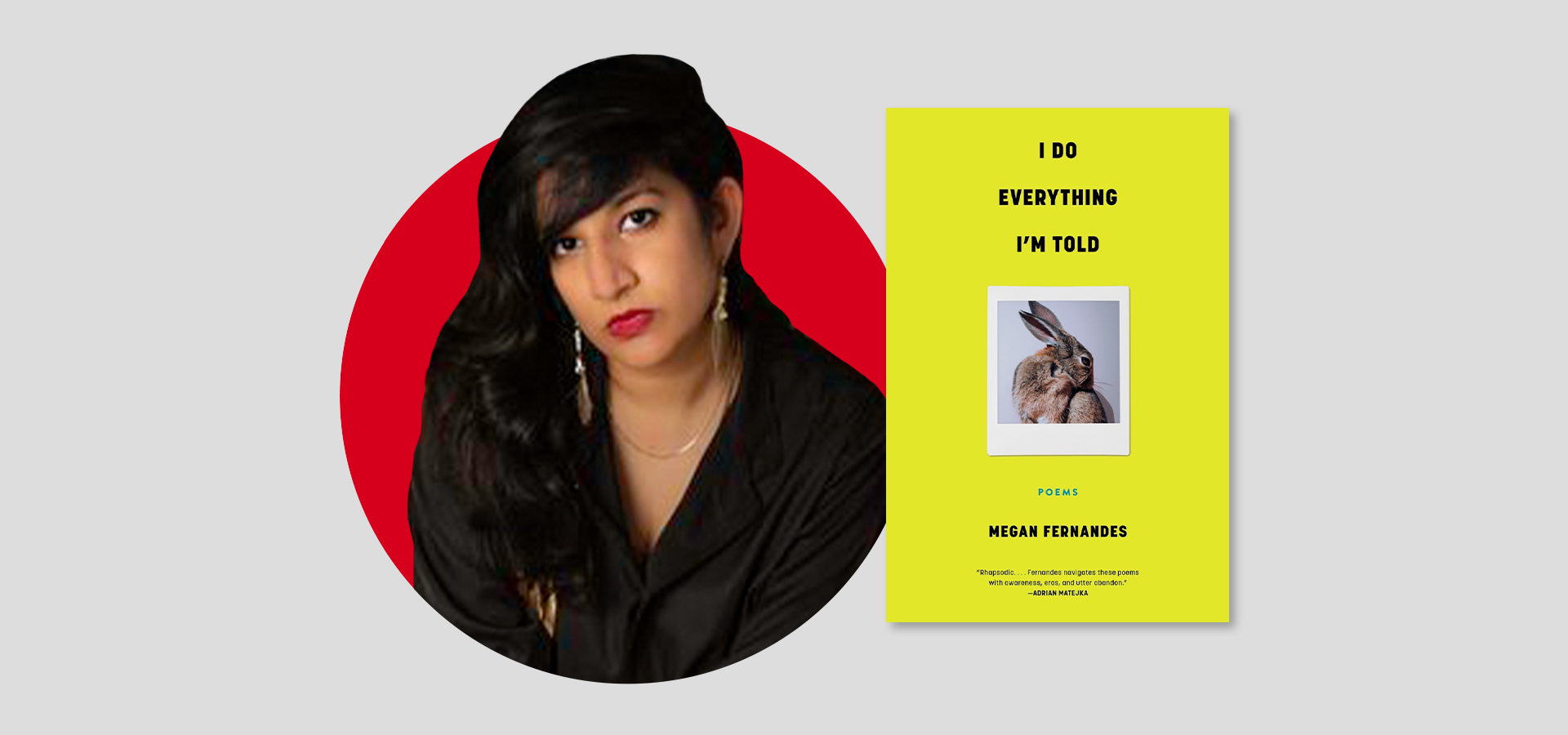

Megan Fernandes | The PEN Ten Interview

August 17, 2023

In Megan Fernandes’ new poetry collection, I Do Everything I’m Told (Tin House, 2023) the love poem is a limitless form. The beloveds are various – friends, lovers, etc.- and the kinds of loves are numerous – affectionate, playful, romantic and more. Fernandes’ speakers span geographies, wander cities and find place in surreal possibilities.

In conversation with World Voices Festival Associate Director, Sabir Sultan for this week’s PEN Ten, Megan Fernandes speaks about the shapes of desire, diaspora and her masterful crown of sonnets at the center of I Do Everything I’m Told. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. I Do Everything I’m Told is a collection of love poems that holds the ‘beloved’ expansively. The collection’s various speakers’ ‘you’ includes not just lovers, but friends, cities, past loves, unfulfilled dreams, and more. How do you define a love poem? How did you approach the idea of love poems in this collection?

A good love poem, in my opinion, is ungovernable. It’s an exploration of an ungovernable feeling. It has a wildness that spills outside cultural norms and that’s why my love poems are often romantic friendships or cartoonish space-travelers or involve multiple people at once or are strangers on red bikes. I prefer love poems that are abundant in how they imagine who or what is worth loving. No center stage spotlight on a single dancer. I prefer the symphony. Even better if the symphony is full of mishap and error.

2. The poems in this collection traverse cities including Shanghai, Paris, Lisbon, New York, and LA, among others. Yet, despite the speakers’ transient relationship to place, the poems are anchored in connection as opposed to dislocation through the speakers’ beloveds that populate the cities. What do you see as the relationship between transience and connection in I Do Everything I’m Told? Between distance and connection?

Transience, distance, and connection are all preoccupations of diaspora, which is part of my family history. Diaspora is fundamentally anti-essentialist, a realm where indeterminacy is both an imaginative and political strategy, a useful way to think through “statelessness” and to deconstruct totalizing understandings of the nation and citizenship.

I prefer a warm rootlessness and am more interested in social formations and subcultures that can exist outside neatly historicized connections since such historicizations always have biases. Recently, I’ve been reading about Asian-American diaspora and queer and feminist theory. In one reading, the author suggests that “The nation not only depends on the containment of femininity but also on notions of kinship and bloodlines that are exclusively heterosexual.” My poems are trying to think about how diaspora might intervene with these logics, to replace a territorial understanding of place with a mobilized feeling of home. To make a home with people not necessarily just in your bloodline. To imagine your people not as a nation, but as an incoherent, atemporal set of intimacies.

“I prefer love poems that are abundant in how they imagine who or what is worth loving. No center stage spotlight on a single dancer. I prefer the symphony. Even better if the symphony is full of mishap and error.”

3. At the center of the collection is a crown of sonnets, Sonnets of the False Beloveds with One Exception or Repetition Compulsion, with each sonnet, except for the last, named after a specific city. [For the reader, a crown of sonnets is a series of sonnets typically exploring one theme, and linked to each other as each sonnet repeats the final line of the proceeding sonnet as its first line.] What was the process of writing that sequence like? What did you want to express through that form?

It. Took. Years. I don’t mean it took years in terms of writing them, but it did take a long time in terms of figuring out why I was trying to write them, what they were trying to do, why I sometimes couldn’t get them to do what I wanted, etc. I mean, we had a quarrelsome relationship. The crown must be a Scorpio or something. I remember yelling “what do you want with me?!” several times while trying to make them flow. The subject matter was hard for me because it was forcing me to untether a lot of repressed, subterranean feelings and events. And that’s why I chose to write a crown with facing erasures, to sort of unpack the tension between what we can say and what we can’t fully put into language, the undercurrent of meaning, a cracked poetic mirror.

My writing process is usually very intuitive and fast, with attention to flow, rhythm, and sonic elements like wordplay and repetition. I’m not usually sticking to a mantra of line length or syllable count or trying to figure out what lines work to open and close poems. And so much deliberateness can often kill a poem. Or make it reek of process. Brilliant sonnet writers like Diane Seuss, Terrance Hayes, Henri Cole, well, you almost forget it’s a sonnet; it just reads like it’s doing what it is supposed to do. A form like a sonnet crown can really bristle with artifice. It needs the conversational. It needs humor and emotional stakes that feel close to the ground in order not to sound like it’s coming in from on high, if you catch my drift. I never want my poems to feel pedantic unless they are doing it ironically.

It was worth all its trouble. I read that crown now and feel immensely proud of it; maybe it’s my favorite set of poems I’ve ever written. When I read it from start to finish, I even get a little choked up. It’s really doing its thing.

4. Words that evoke acts of worship and images of priests, churches, and various Gods appear across the poems in this collection. In the poem Drive, the speaker even mentions applying to divinity school. What is the sacred in this collection? How did you approach it?

I’m into the gaudy iconicity of Catholicism. I grew up Catholic and went to Catholic school, was taught by nuns who lived on the premises, was required to go to confession and mass and take religion classes every day of the week on the sacraments or whatever. But I was always a good critical thinker and never bought into the ideology of Catholicism, which always felt punishing, shame-oriented, violent, sexist, and homophobic.

But still, I like the gravitas of the moment when you walk into an old cathedral, its cold stone walls humming with history. And I’m quite interested in how all families (including my own) navigate the hypocrisies of their faith. Watching someone being a hypocrite or holding a contradiction with unease is actually fascinating. I asked questions constantly about god as a kid, as certain kids tend to do. My interrogations were clearly a nuisance.

I do believe in the sacred. It’s a trembling feeling. And it’s probably more related to time. I feel it when I am in the presence of a lot of history, a lot of fraught history. I feel it where I sense pain, but also, of course, where I sense a great, unexpected intimacy with someone, which the book cherishes deeply–that stranger intimacy, that little brush with someone who we don’t know but still feel connected to for whatever reason.

“A form like a sonnet crown can really bristle with artifice. It needs the conversational. It needs humor and emotional stakes that feel close to the ground in order not to sound like it’s coming in from on high, if you catch my drift. I never want my poems to feel pedantic unless they are doing it ironically.“

5. In the poem, I’m Smarter than This Feeling, but Am I?, you write “You want what O’Hara wanted, I think, which is a kind of boundlessness/that won’t kill anyone.” ‘Boundlessness’ became a key word for me as I read this collection. The poems in the collection traverse geography, time, realities, and even the Milky Way. They allude to other poets’ works, dip into the speakers’ memories, and even imagine the memories’ of the speakers’ beloveds. What do you see as the relationship between boundlessness and restraint in your work?

Oof, I wrote a whole essay on the subject recently. There’s an erotics to both.

There is nothing safe about boundlessness despite all the faux enlightenment nonsense people say when they insist everything is connected– like yes, okay, if everything is connected, then maybe we should be taking our shared vulnerability more seriously, right? But we don’t. And we also are living in the era of “boundaries” (a kind of restraint) which is some other really dollar-store self-help capitalist talk that means essentially nothing concrete. In sum, I’m really suspect of the faux-spirituality of boundlessness and the faux-self-care individualist politics of boundaries.

Boundlessness and restraint, in my work and in life, are in a constant ebb and flow. And desire is often at the threshold of how we practice swimming in that ebb and flow. Desire, and how it’s shaped by gendered, nationalist, and racialized structures, deserves to be interrogated, and this is what so many of the poems in the book explore, either through their subject matter or their experimentations with form. My own imagination is a time-traveling one and I sort of operate, as do many poets, with a sense of simultaneity, a sense that personal histories, political histories, family histories, and romantic histories are often all stacked up in a single moment and it can overwhelm us. How to filter out what is meaningful when one is overwhelmed? That is the work of moving in between boundlessness and restraint, being restrained enough to filter out what feels like it doesn’t matter, being open enough to let meaning take shape. And intimacy often blooms at those thresholds or borders.

6. What do you see as the biggest threat to free expression today?

What’s happening in K-12 education. The violent political regime particularly against Black and trans kids, but also more broadly, queer people, POC, and women/femme people in our classrooms is disgusting. Banning books. Ensuring a curriculum that reflects the goals of white supremacy. Trying to force kids to share information about their gender identity or menstrual history. Banning education about sex and sexuality. All of it is reprehensible, fearful, hateful trash. These people who are proposing these bills are so afraid. They are afraid of a personhood outside themselves, outside their own protagonism. They want everyone to want to be them. They think they are Power, but they look like scared fucking chickens who are picking on kids, and that is unforgivable. You lie and shame these kids and call it an education? Honestly, how dare you.

7. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I think love poems are the most daring things we can write. It’s terribly embarrassing to be in love and it’s even more embarrassing to write poems about it. Like, you had your little feelings, and then you wrote them down? And then you PUBLISHED them? For people to read?! Mortifying.

I’ve written many things I’d like to take back, but I’m also asking for forgiveness for my younger self. A visual artist I really respect told me it’s useless to have a precious relationship to one’s art. Not everything is a masterpiece. Not every epiphany is a dictum that will be eternal. And the discourse of mastery and the eternal are quite problematic, really. I write ephemeral poems from a space of deep respect for ephemerality. Any poem I feel some unease about now is also a poem where I was trying to figure something out subconsciously. The epiphanies are a bit clumsy, as they are when we are young (and often also when we’re old).

8. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I think all kids realize that language can be weaponized when they have their feelings hurt by a passing comment. Being a youngest child, I saw my older sister get picked on in elementary school and some of it was definitely about race. One girl told her to go back to the jungle and ride elephants. I still think about what I might say if I ran into her at some sad suburban shopping mall, which she probably frequents because, let’s face it, she was so basic. Her mother came to apologize to my mother, and my mother was very classy, gracious about it, but I was not. I knew that if her kid was saying that stuff at nine years old, she had heard it in her home. Language is inherited. That’s how power is reproduced.

“My own imagination is a time-traveling one and I sort of operate, as do many poets, with a sense of simultaneity, a sense that personal histories, political histories, family histories, and romantic histories are often all stacked up in a single moment and it can overwhelm us.“

9. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Definitely Bhanu Kapil. I’m always so interested in what she’s up to because every book is really different and to me, that’s the mark of a great poet. Someone who has a sensibility, but also curiosity, exploration, testing the limits of their imagination and talents. I love almost every Ellen Bass poem I’ve ever read. Terrance Hayes, of course, is another poetic genius who also manages to be surprising with every new book and some of his illustrations and drawings–the way his mind works, it’s so particular and unusual. I dig that. In my generation, I love Taylor Johnson, Virginia Konchan, Fiona Benson, and I just read some brilliant poems in a recent issue of Poetry Magazine by Brian Gyamfi that really hit.

10. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

I adore the films of Agnès Varda. They are whimsical, joyful, tender. She loved people, you can really get that in her work, particularly Daguerréotypes, a favorite of mine where she has these little vignettes of people who lived on her street. She got what made up a street and is a master of scale and intimacy. I’ve learned so much from her, about how to love people, how to create portraits, how to be a little creaturely as a speaker.

Megan Fernandes’ most recent book of poetry is I Do Everything I’m Told, published by Tin House Books in June 2023. Her poems have been published in The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, The Common, and the Academy of American Poets, among others. An associate professor of English and the writer-in-residence at Lafayette College, Fernandes lives in New York City.

Bronwyn Fischer | The PEN Ten Interview

My focus was just on the insecurity of being. Everything that happened narratively came from focusing on that feeling as much as possible.

Andrew Ridker | The PEN Ten Interview

By: Anna Lasek | August 17, 2023

In a way, the structure of the novel reflects one of its primary themes: the desire to break away from one’s family, and the bonds that invariably pull one back.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths | The PEN Ten Interview

By: Malcom Tariq | August 11, 2023

This book was my attempt to assure young Black girls that there are beautiful, resonant ways to live, to investigate love, and to celebrate themselves.

Ben Purkert | The PEN Ten Interview

I followed Seth on his downward spiral and simply tried to keep up with my pen. And no, I didn’t worry that my novel was too dark. I only worried that it not be boring.