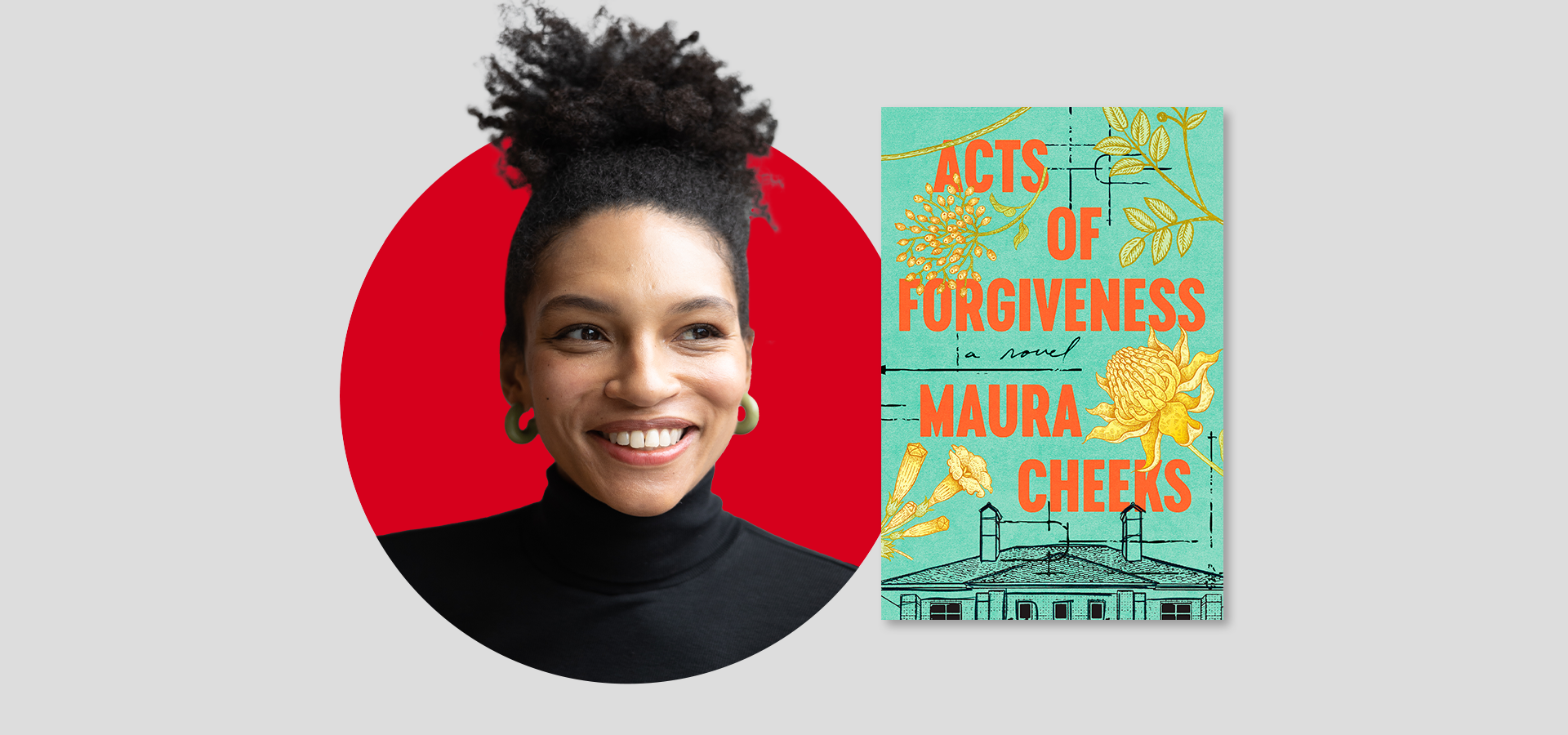

Maura Cheeks | The PEN Ten Interview

February 15, 2024

Maura Cheeks‘ debut novel, Acts of Forgiveness, imagines a United States in which reparations legislation is passed. Named the Forgiveness Act, the law provides reparations of $175,000 to individuals who can prove they are descendants of the enslaved. Centered on the Revels, a Black family in Philadelphia, the novel takes readers on a journey that explores race, personal history, and dreams deferred.

In an interview with Jared Jackson, Program Director for Literary Programs and Emerging Voices, Cheeks discusses system inequalities, archival research, and whether forgiveness can be political. (Bookshop)

1. In 2019, for The Atlantic, you wrote about the racial wealth gap. Your debut novel, Acts of Forgiveness, imagines the approval of reparations for Black Americans who can prove they are descendants of the enslaved. Having first begun to explore the topic through nonfiction, what made you turn to fiction? What did the novel allow for that journalism didn’t?

I turned to fiction to explore answers to questions we haven’t yet been able to solve. I’ve written this before elsewhere but trying to explain why reparations is important can feel like Sisyphean task and I feel like sometimes nonfiction writing is about trying to provide evidence for the point you want to make. I wanted to explore the world that exists after the choice has already been made. Where it wasn’t about trying to get reparations passed but navigating the world after it’s already a reality. My goal with the book was trying to put some humanity back into a conversation that is often stalled by numbers or political debate.

2. There’s a question in the novel that Willie, the novel’s protagonist, ponders over how she would answer if she was a journalist: “Can forgiveness be political, and can it be lasting?” It made me wonder if this was a central question when you began to explore the idea of the novel, and if so, having now written the book, where do you land on this question?

I didn’t have this question explicitly in my mind before I began writing, but in exploring the concept of “forgiveness” I was interested in the idea that the work of forgiving falls on the aggrieved party. An argument you sometimes hear around reparations is “we’ve apologized, let’s move on” but I think the subtext of such an argument is that all should be forgiven, as if that is a simple ask. I was interested in exploring the irony of a government asking for forgiveness, and also exploring the burden the government places on Black people even when it is supposedly doing the “right thing.” This comes to life in the book through families having to prove they are worthy of Forgiveness.

“I wanted to show what one is willing to give up to make sure that the positive aspects of financial and familial inheritance are carried forward, but in so doing I also wanted to explore the cost of making that decision.“

3. Four generations of one family are featured in the novel. What role did the theme of inheritance-financial, familial, emotional—play into your conception of the book? How did you wish to show its importance, and for Black families in particular?

Inheritance is one of the primary themes I was thinking about when I started writing this book. I think for Black families especially it can be both something that’s inspiring but it can also feel like a heavy burden to carry. I wanted to show what one is willing to give up to make sure that the positive aspects of financial and familial inheritance are carried forward, but in so doing I also wanted to explore the cost of making that decision. When you have survived so much, I think individual wants and needs are sometimes seen as less vital than preserving the whole. There are both pros and cons to this. Knowing that your choices matter, that you don’t have the luxury of choosing paths that don’t take your family into account, but also maybe you lose something in the process. That’s what I wanted to explore, the duality of that experience of inheritance.

4. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I read a lot, and I generally don’t continue reading a book unless I’m feeling inspired by it in some way. I think consistently engaging with books that push me to think about different styles and forms keeps me excited and motivated to continue improving my own work. I prefer to write in the morning from 5:30am until about 7 or 7:30. I try to write a draft all the way through without much self-editing. This allows me to get a feel for the characters and to see where they want to go. Then I start researching all the areas I feel are lacking specificity or places where I know I need to go deeper.

“I was thinking about what would have to be true for someone in power to take a stand for reparations and push it through. And I thought maybe what it would take is someone feeling some sort of deep personal responsibility. Could white guilt be put to good use?“

5. In order to obtain the documents necessary to receive reparation payments for her family, Willie must travel to Mississippi and go through the archives—land deeds, marriage certificates, proof of sales. What research, if any, did you do for the novel? Are there resources, historical precedent, or figures that proved paramount?

I traveled to Jackson and Natchez while I was researching the book and met with employees at the Mississippi Department of Archives and the Historic Natchez Foundation. They were instrumental in helping me write about Willie’s journey, and they helped me imagine what it would have been like to go there with limited information and try to find what you needed. I also relied heavily on a book called Finding A Place Called Home by Dee Parmer Woodtor to understand what goes into genealogy research and to better understand what is conveyed through certain documents. I researched the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, as well.

6. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

I think the current tendency to place moral judgement on artists for questions they explore in their art is dangerous. I’m worried it will result in self-censorship and limit the art people feel they can create. Just the fact that I’m nervous to release a book about reparations because of the vitriol that will likely be directed my way is an example of this. If I thought too hard about it, I probably never would have written the book.

7. The novel portrays a speculative United States, but not one too far removed from our present. How did the world we’re living in now—its political debates, divisions, and concerns—inspire aspects of the novel?

I started writing the book in 2019 after working on an article for The Atlantic about the racial wealth gap. So, when I first started writing the book, I was very much thinking about the country’s inability to deal with the systemic inequalities we have been facing for a long time, like the fact that the proportion of Black people living in poverty has stayed at relatively three times that of white people for over fifty years. Then obviously while writing the book the world changed and it pushed me to keep writing because suddenly this thing—reparations—that I was imagining was being talked about in a serious way. There are brutal murders referenced in the book and those refer to the fact that I was emotional after reading and watching the videos about Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd.

8. The character who pushes for, and eventually signs into law, the Forgiveness Act, as it’s titled, is Elizabeth Johnson—a former mentor to Willie turned U.S. senator, and then president. She’s also the descendant of President Andrew Johnson. When did the idea to connect Elizabeth Johnson to the notorious legacy of President Johnson come to mind? What did you seek to explore with this decision?

I was thinking about what would have to be true for someone in power to take a stand for reparations and push it through. And I thought maybe what it would take is someone feeling some sort of deep personal responsibility. Could white guilt be put to good use? I was also thinking a lot about Elizabeth Warren’s policies and her support of the wealth tax and I appreciated her ability to try and think of creative solutions we haven’t tried before.

“If you work consistently on improving your craft, then you’re a writer. What that looks like will be different for you based on where you are in your life.“

9. What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

I never wanted to hear this when I was starting out, but it is true that if you write, you are a writer. More specifically, if you work consistently on improving your craft, then you’re a writer. What that looks like will be different for you based on where you are in your life. It might mean waking up 30 minutes earlier so you can work on one sentence or one scene before your full-time job. It also might mean reading books on craft. One piece of advice I wish I had gotten earlier is to define what “being a writer” actually looks like for you. What does success mean? Be specific and set goals and then build on those goals once you start achieving them.

10. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Brandon Taylor, Garth Greenwell, Percival Everett, Kirstin Valdez Quade, Brit Bennett, Raven Leilani, Natalie Bakopoulos, Olga Tokarczuk

Maura Cheeks’ work has been published in the Paris Review, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Harvard Business Review, Tin House, and others. In 2018 she was selected to attend Tin House’s Winter Workshop and was one of seven people selected to attend Jamel Brinkley’s Tin House Craft Intensive. In 2019 she was awarded the Masthead Reporting Residency for The Atlantic’s first residency program where she worked on the above-mentioned feature article that would later inspire the idea for Acts of Forgiveness. Maura graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and received a certificate in publishing from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. She also holds her MBA from NYU.

Kacen Callender | The PEN Ten Interview

I wanted to offer the idea that power is naturally inside of all of us, and that we can feel empowered and worthy and loved even when rejected by others for not meeting their criteria of worth.

Vanessa Chan | The PEN Ten Interview

I don’t believe you can go through a publishing journey alone, especially as a writer of color.

Andrés N. Ordorica | The PEN Ten Interview

Guarding generational stories and wisdom is important especially when so many stories are now being policed.

Hisham Matar | The PEN Ten Interview

I am fascinated by how time is both linear and circular, by how any given moment often contains within it remnants of the past and our aspirations for the future.