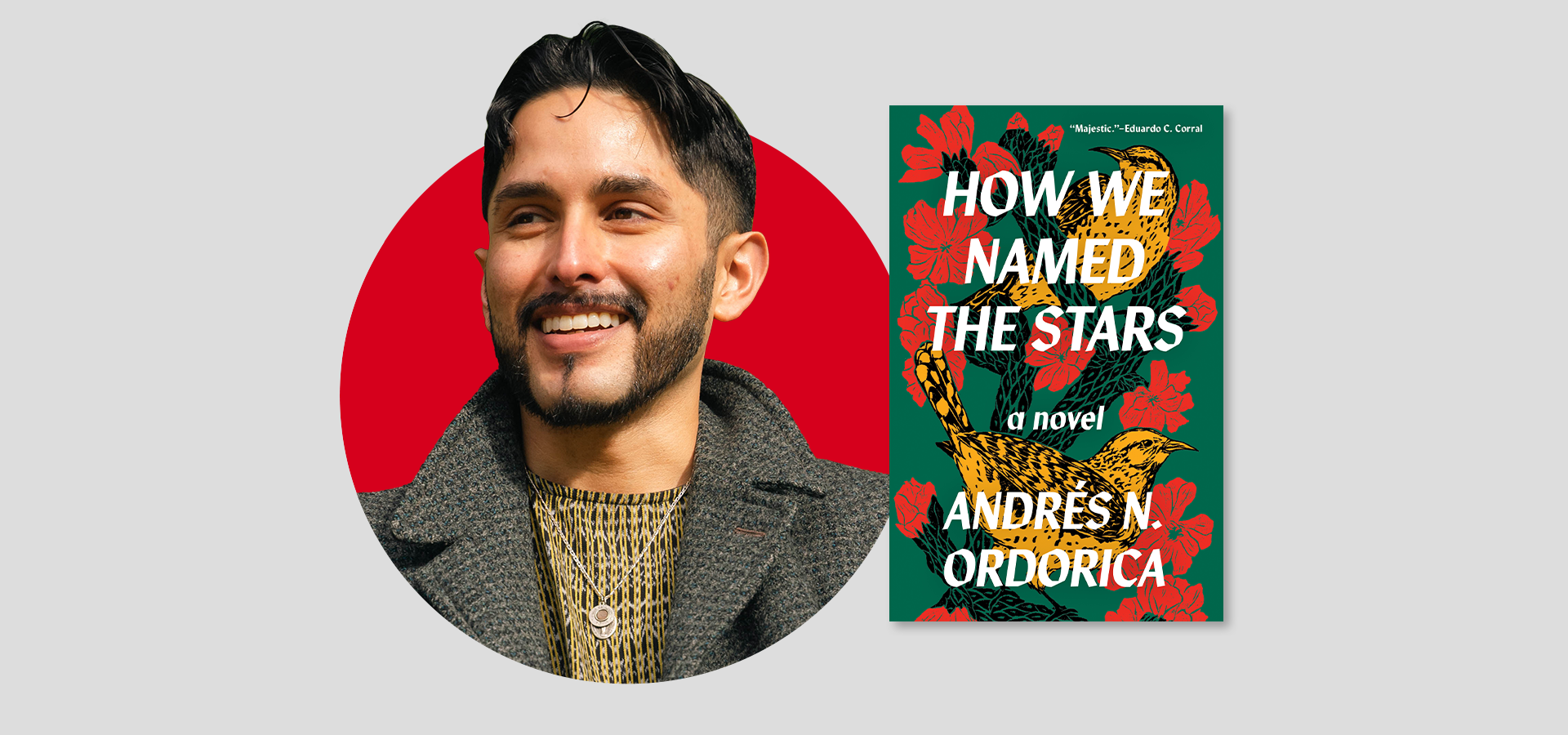

Andrés N. Ordorica | The PEN Ten Interview

January 25, 2024

Andrés N. Ordorica tells a story of love, and self-discovery in How We Named the Stars (Tin House, 2024). Daniel de La Luna is a young latin-American man attending his first year of college. At Cayuga University, he finds himself roommates with Sam–the attractive soccer player who proves to have more empathy and care than your typical varsity jock. Through their freshman year before Sam’s sudden passing, Daniel experiences a first love that inspires him to live up to his potential. Ordorica’s prose is lyrical and descriptive as Daniel comes to life by coming of age. Detailing what it’s like to go through love and loss, How We Named the Stars is a beautiful story of queer desire across generations.

In conversation with PEN America’s World Voices Festival and Literary Programs Coordinator, Sarah Dillard, for this week’s PEN Ten, Andrés N. Ordorica discusses love, representation, and the importance of mentorship in How We Named the Stars. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. What was the first spark that inspired you to write How We Named the Stars?

Daniel and Sam came to me nearly ten years after graduating from college in Ithaca, NY and I think I was at a very reflective and slightly nostalgic point in life nearing my thirties. I had this deep interest in capturing what love felt like at that age of eighteen/nineteen in all its messy, ugly glory. Much of the story’s meat changed over the five years or so of drafting and rewriting until I reached the final version of the novel, but the bones of these two characters’ love story has stayed pretty much the same since I first started writing it.

2. The novel is written retrospectively. Why did you decide to do this?

For me I think there is such power in reflection and memory. As a queer person, I think I am always working through my understanding of “the self” in relation to various seasons of my life and to do this it can only be done retrospectively. Trying to untangle who I was, and how I might have changed, especially in relation to my sexuality or understanding of my particular version of manhood or masculinity. First love and first loss are both daunting rites of passage, and allowing Daniel the ability to reflect on it, a year on, or in the case of Sam’s death, only a few weeks after that life changing moment, felt a rich opportunity to portray these experiences. I don’t know if the story would have had the same quality or impact if Daniel was experiencing it at the moment of narration. I think having that lens of reflection and processing of grief added the nuance I needed to tell this specific story–it gave a bit of a buffer that made the trauma a little less harrowing.

“As a queer person, I think I am always working through my understanding of “the self” in relation to various seasons of my life and to do this it can only be done retrospectively. Trying to untangle who I was, and how I might have changed, especially in relation to my sexuality or understanding of my particular version of manhood or masculinity.“

3. Daniel gains a new perspective on events as he reflects on what has happened in the past. Do you ever look back on your writing with a new point of view? If so, how do you accept what you can’t change?

I struggle with this as I am my own worst critic and it can veer into intrusive thinking (I know every writer says this!). But I truly am critical of my writing. I am actively trying to be kinder to myself, but it is hard to shift the cringe feeling of reading or looking back on previous writing, especially once published. This is easier with poetry because I really only ‘look back’ when I perform it. I think the act of regularly performing my poetry at festivals or open mics breathes new life and nuance into a poem, into the words I use, or images I depict, whereas with prose, it feels pretty locked in. So I guess it feels uncomfortable to read back and come face to face with writing that seems very personal, and maybe sometimes earnest, or dare I say, saccharine. This novel is interesting because that earnestness was deliberate and very necessary to make a character like Daniel – who is at a very malleable point in his life – come alive. He needed to be earnest, a bit of an overthinker, and awkward at love because those were at his core, true qualities of that age. But being the writer, and basing him loosely on myself, I am met with my own earnest, awkward, cerebral self when I read through the novel. As a writer, I can only really only move forward, because as you say, I can’t change and shouldn’t want to change what I have written, instead I want to celebrate it and give it the flowers it deserves. I truly love Daniel and Sam so much, but I also look forward to writing characters at other points of life in which maybe I can afford to give them a slightly rougher exterior, make them a bit more jaded, worn if you will. Whereas Daniel is a beautiful character to have magicked because he is so sweet, a “naive little cherub” as one of the other characters asserts early on in the novel.

4. Throughout the novel, Daniel encounters inspiring mentors. Do you have people in your life you have mentored you? How have they inspired where you are today?

Most definitely! In my writing career, I am so indebted to other writers like poets Hannah Lavery and Nadine Aisha Jassat, both of whom taught me how to hold space for both the personal and the slightly altered versions of ourselves in writing. I feel so fortunate to have such a strong writing community in Scotland where I have made a life of myself, alongside fellow writers of color whom I adore like Alycia Pirmohamed and Rachelle Atalla. I also am so indebted to writers of the past, or writers’ early work that I can unearth from a queer or POC cannon, such as James Baldwin, Sandra Cisneros, Edmund White and Edwin Morgan who demonstrate the possibility of writing intimately about sexuality or race, sometimes at the same time. But in terms of Daniel, I was fortunate to have a solid group of friends in university who guided me through the highs and lows of becoming an adult. I survived that chapter of my life fairly unscathed and that is so very much in thanks to the power of friendship which I hope this novel evokes.

“As much as there are elements of my being in Daniel, he is so very much molded by stories of my mother and the larger family lore passed on by maternal aunts and cousins.“

5. As Daniel falls in love for the first time, he discovers a lot about himself. How does who we love shape or reveal who we are?

Love is such a rich plot device for showing a character’s growth, in the same way we learn about ourselves as we fall in and out of love. I mean until you are in a romantic/sexual relationship with someone, whatever that looks like, how can you really know how you love or how you get angry or how another person can truly disappoint you? It is so different to the love you might have for a sibling or grandparent or friend, especially when it is a queer love. Those other relationships shape us, but this story is rooted in a specific type of love in which the protagonists grow up believing is not acceptable or has to be hidden. As the novel unfolds I think we see Daniel grow from being tightly wound and unable to articulate his feelings to someone who is braver and kinder to both himself and to Sam, especially as both are two young men struggling with what their love might mean out in the wider world. I see Daniel’s journey as that of a caterpillar to a butterfly and the throughline at each of those stages of evolution is love and its aftermath.

6. In Mexico, Daniel not only meets relatives, but meets a part of himself. What role has your family played in your development?

I am very fortunate that so much lore is alive and well within my family. Both sides of my family have roots in México and the second half of the novel is really a means of celebrating that facet of myself. So much of Daniel’s time in México is informed by my own adolescent experiences of visiting Chihuahua, as well as stories passed down to me through my mother whose family hails from the north of México. Storytelling is such a rich tradition within my maternal side of the family, and I always say my mother is the first person who taught me the art of storytelling. Growing up I lived for her stories of growing up as a daughter of immigrants, her experiences of having to serve as translator at the age of seven, code switching between her life as an American kid growing up in the 1970s and 80s with Mexican parents who still pined for the homeland, to her colorful memories of visiting Chihuahua. As much as there are elements of my being in Daniel, he is so very much molded by stories of my mother and the larger family lore passed on by maternal aunts and cousins. My growth as a writer and what I choose to write about is a product of coming from a family who celebrate, with such fervor, our culture, our histories, and our languages, both English and Spanish.

7. There are comments throughout the story on Caygua University’s lack of BIPOC representation in the curriculum. What was your college experience like with regards to assigned reading? What books by BIPOC authors were key to your education?

I love this question! My experience was probably like many other English literature students who went to private liberal arts colleges on the east coast of the United States in the mid to late 2000s: stale, male and pale. I did not take a course that had a substantially diverse reading list until my final year of college when I took a “Multicultural American Literature” course. I took courses in Jewish American Literature, Irish and British Literature, countless courses from the Renaissance to Restoration, courses on Great American Writers from the 1800s and Victorian Literature, but had only one course that featured writers who remotely related to my experience as a queer person of color from an immigrant background. That is not to say those other courses were not of value. Some of my most favorite writers I was introduced to at that time such as Nicole Krauss, Ben Jonson, and Samuel Beckett. But so much of my education in BIPOC literature has come since my undergrad from other writers, activists, community organizers, going to literary festivals, librarians and booksellers recommending reading lists to me. But at Daniel’s age Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Gish Jen’s Mona In The Promised Land, Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, as well as Suzan-Lori Park’s Topdog/Underdog were life changing.

8. Despite being more shy and timid, it is Daniel who breaks the silence after his first kiss. Have you ever put yourself out there to be rejected–either professionally or personally? What was that like for you?

I think choosing to be a writer is to put oneself in the position of constant rejection in a quest for validation or at least acknowledgement. I have been writing professionally for over ten years, so there have been many moments professionally in which I have been rejected whether from journals and magazines or in the early days of trying to land an agent. How I write is so very much based on the personal, so to feel like something has not landed with another person–say editor or agent or publisher–it can feel like a rejection of both the writer and the work which is like a double whammy. But I guess in the same way love blossoms, when a story finds the right person, well that can grow into a deeply meaningful and rich experience.

“Guarding generational stories and wisdom is important especially when so many stories are now being policed, particularly queer stories or those that force us to confront the world’s ugly, imperial, colonial, and violently racist past (and dare I say present), but also those of us writing from the margins, we have a right to write to joy, to the quotidian, to all that exists beyond trauma.“

9. In the story, a lot is passed down through generations–legacies, trauma, wisdom. What’s the best way to manage what we inherit?

My only advice is that we all can choose what we carry forward. Sometimes we have to learn to let things go or die out, especially if they do not serve us. This feels an especially hard learned lesson for those of us in the LGBTQIA+ community. Daniel has a moment in México, momentarily away from his grandfather, on their family’s ancestral farm and he realizes that nothing of that past speaks to him. Bluntly put, the person Daniel is would not have the skillset for ranching or manual labor, but he as someone interested in story and writing knows that he can hold space for it and write about it in future (the heat, the flora and fauna, those are things he can choose to capture in story). Equally he can let those family memories stay in México if need be–not everything from our family’s pasts, or the communities we belong to, has to be carried forward. Guarding generational stories and wisdom is important especially when so many stories are now being policed, particularly queer stories or those that force us to confront the world’s ugly, imperial, colonial, and violently racist past (and dare I say present), but also those of us writing from the margins, we have a right to write to joy, to the quotidian, to all that exists beyond trauma.

10. Daniel writes so the story of him and Sam isn’t lost. Why do you write?

I have always been an observant person. From a very young age, I relished moments of bearing witness to the world around me – maybe that is down to being a middle child. But I adored any chance I got to just sit and be with the adults at parties, eavesdropping on their conversations, or sitting in parks and just watching the world get on. At the age of twelve, I attempted to write my life’s autobiography (I don’t even know if I really knew what that meant). But, I felt an urgency to write down my memories after living overseas for the first decade of my life, having just moved to the middle of nowhere in northern California. I am a deeply emotional person, and always have been, and probably feel things too strongly (water sign!) and so I feel there is so much emotion and feeling surging through my body that I have something to say about it, a need to carve it into something that might help others make sense of what it is to exist. I write as a means of teasing out those strong emotions or feelings, as a means of processing life, and perhaps, wrangling with aspects of my queer journey that I have not yet been able to settle. I think as I move through the world my queerness will be in communion or antagonism with numerous things–aging, love, masculinity, losing friends and loved ones, learning to own my version of family–and so I imagine I will always have something to write about.

Andrés N. Ordorica is a queer Latinx poet, writer, and educator. Drawing on his family’s immigrant history and his own third culture upbringing, his writing maps the journey of diaspora and unpacks what it means to be from ni de aquí, ni de allá (neither here, nor there). He is the author of the debut novel How We Named the Stars (Tin House) and the poetry collection At Least This I Know and currently resides in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The PEN Ten Interview Series

Hisham Matar | The PEN Ten Interview

Zahra Hankir | The PEN Ten Interview

Raj Tawney | The PEN Ten Interview