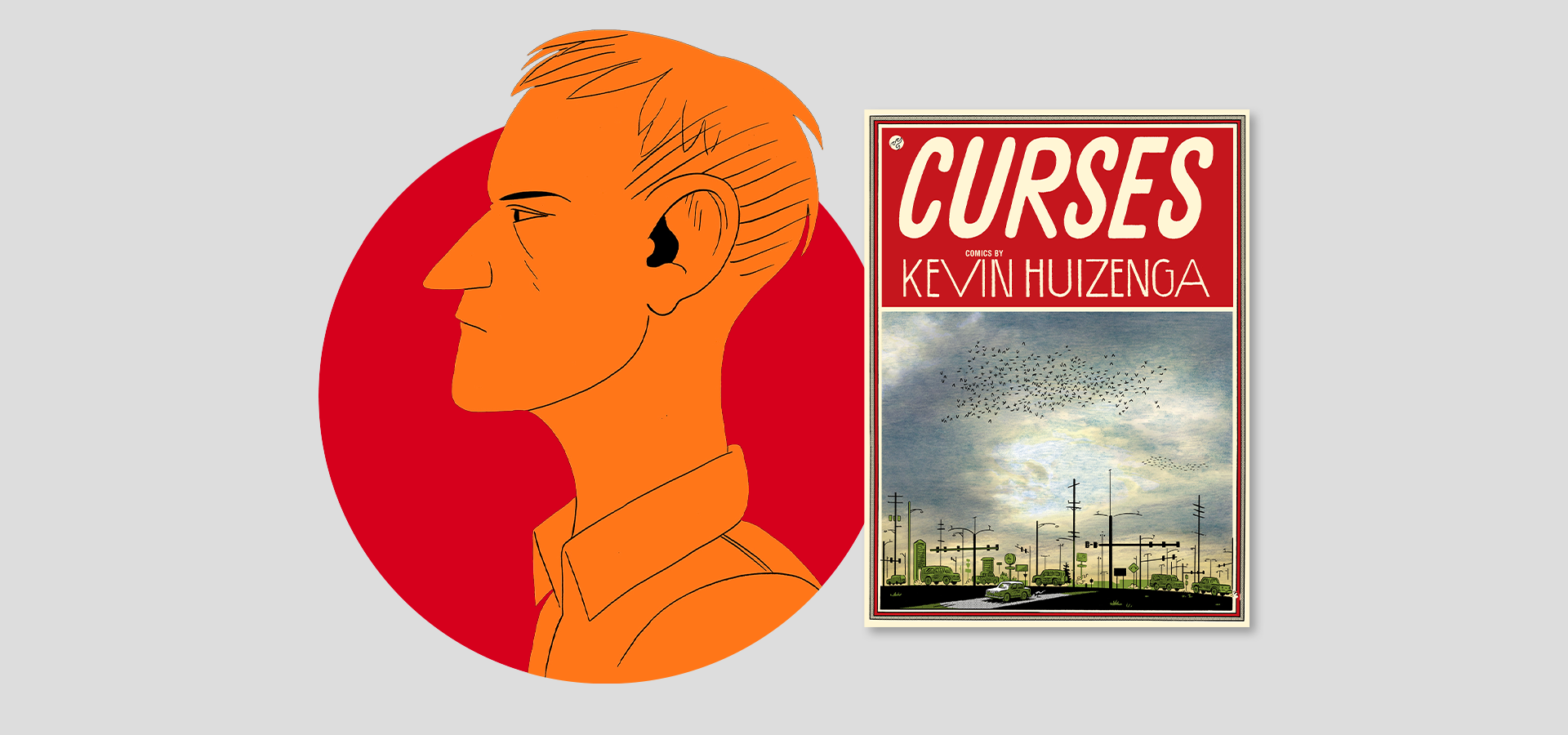

Kevin Huizenga | The PEN Ten Interview

February 27, 2024

In his collection of stories, Curses (Drawn & Quarterly, 2024) Kevin Huizenga tackles parenthood, theology, politics, and capitalism through surreal monsters and mundane suburbs. Originally published in 2006 and included in TIME’s top 10 comics that year, Curses has been rereleased in a deluxe paperback with deleted scenes, first drafts, and character sketches.

In conversation with PEN America’s Artists at Risk Connection’s Communications and Editorial Assistant, Valentine Sargent, for this week’s PEN Ten Kevin Huizenga shares his process in culminating the nine stories into one cohesive collection along with the influences of Midwestern life, Chekhov, a Victorian ghost story, and others. (Bookshop)

1. You mention in previous interviews that Glenn Ganges allows you to investigate different complicated experiences without the need to recreate a character. How has Glenn Ganges transformed throughout the years? What has he taught you?

Glenn is there to be invisible, in a way. He’s more like an actor playing a part, in my mind, than he is essentially himself. He plays different parts in different stories, even though in Curses he’s a kind of “suburban dad” throughout some of the stories, and the stories where he’s not could conceivably be the “same Glenn.” He’s like one of those cartoon characters who is always roughly the same age, and lives in a world where he could conceivably have infinite adventures. Something like Mickey Mouse. Mickey Mouse “plays” the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, or slays the Giant, but he’s also somehow Minnie’s boyfriend and Pluto’s owner, too, if you know what I mean.

2. The curses in the collection lean toward the impersonal. Why not choose the term “misfortunes” or “bad luck” – what attracted you to use the word “curses” to describe these stories?

The stories were all written individually with no plan or sense that they were part of the same book–I didn’t think of the themes that ties them together until I had the chance to put the book together, and realized there were “rhymes” and repetitions. I like to be productive, and sometimes being productive means taking an idea you thought up in a previous story, and expanding on it, or turning it around to look at it from another angle. I also repeat important objects, like feathers, or moons. The decision, to be honest, is sometimes arbitrary and expedient, and the “meaning” if any is found after. Putting the book together, I realized there was a conceptual throughlines, misfortunes and barrenness on the one hand, and overproduction and sprawl on the other, that I had no thought of when I was writing them. I suppose “Jeezoh,” the last story did get drawn after I had the idea for the title and how I’d tie the stories together, and so the Glenn and Wendy in that story are basically the same ones as in the Sprawl Trilogy.

“I like to be productive, and sometimes being productive means taking an idea you thought up in a previous story, and expanding on it, or turning it around to look at it from another angle. I also repeat important objects, like feathers, or moons. The decision, to be honest, is sometimes arbitrary and expedient, and the “meaning” if any is found after.“

3. Since these nine stories mostly appeared in various anthologies, how did you place them within this collection under this theme? Did you find ways in which they connected to find a coherent flow from one story to the other or did you have to rewrite some of the stories to allow them to better fit within the collection?

I kind of addressed that in the previous question, but I’ll say further that I did not need to adjust anything to fit, I got lucky that everything fit together pretty well. The stories were all drawn roughly in the same 3-4 year period, and comics work is slow, so I was in the same mindset, throughout that time, I guess.

4. Each character in Curses is an ordinary middle-class individual. Was this done for readers to easily relate to the characters or did you approach these characters with a sense of personal familiarity?

It just worked out that way, since that is roughly my class position, at least when I was younger, and the kind of world I know about, to write about. I suppose I take issue with “normal” for describing them. I suppose you could say they are “generic” in the sense that the kind of sitcom Simpsons-y timelessness I was thinking about, the cartoon characters that never age, and thus can have endless adventures while somehow resetting at the end of each “show” back to their roles as dad, mom, doctor, etc.

“I wanted to contrast the everyday suburban life of these kinds of believers with the kind of hair-splitting debates I’d see in the books, arguing over translations of words, and so on, regarding such an amazing belief, the particulars of which were also amazing. Was it eternal torture? Eternal abandonment? What kind of suffering?“

5. Hell takes on different meanings and settings within Curses as it takes on the form of a monkey that haunts a reverend, a strip mall on 28th street where a human-eating ogre lives, and the classic interpretation of flames, torture, and demons. What motivated you to explore hell in these various definitions and interpretations?

Only the “Jeepers Jacobs” story is the “orthodox” Christian hell, for the unfaithful. The other stories I think of as more horror stories, of extreme suffering. I suppose I was motivated in the former case by growing up “in the Church” and it slowly dawning on me what the doctrine was all about, and then wondering about the kind of men who write scholarly theological defenses on the topic. I wanted to contrast the everyday suburban life of these kinds of believers with the kind of hair-splitting debates I’d see in the books, arguing over translations of words, and so on, regarding such an amazing belief, the particulars of which were also amazing. Was it eternal torture? Eternal abandonment? What kind of suffering? At the time I was influenced by Chekhov, who said something like that a fiction author ideally wouldn’t show their own position in an argument, in a story, but should try to depict the kinds of people who have that kind of argument.

6. Rev. Mr. Jennings and Jeepers Jacobs are consumed with hell in vastly different ways yet culminating in the same outcome within their stories. Why did you choose to explore the abstract idea of hell through these two characters?

I appreciate that you’re trying not to give anything away, no spoilers! but I have to take issue with the idea that there was the same outcome, except maybe only in the broadest sense. I think of “Green Tea” as a horror story–it’s an adaptation of a Victorian ghost story, and I followed the original very closely. The story of Jeepers and hell (and golfing and constipation) was my attempt to weave some ideas together and see what would happen; the ending of that story seemed to me to be inevitable, given these ingredients, and the story breaks off in a way that I hope leaves some different possibilities open, for the reader to ask or guess what they think happens next.

7. “Case 0003128-24” stands out in the collection as it is Glenn-less and the illustrations are a tranquil landscape contrasted with the story of a child up for adoption. What makes this story fit within the theme of Curses?

Adoption of course also appears in “28th Street,” where Glenn and Wendy are trying, and failing, to become parents, either through having their own or adopting (Wendy’s dark past is a red flag.)

8. There are multiple curses in “28th Street,” the obvious one being that Glenn and Wendy aren’t able to have a child, but there is also the subtle curse of fossil fuels: gasoline, plastic shopping bags, and styrofoam. What made you decide to use these items – commonly referenced as toxic – as magic tools?

You get at the idea very well with your question; everything runs on oil, and that’s a problem, a deep one, woven through all of what suburban sprawl is all about.

“When a story starts to form, ideas cluster around and start to spiral, like a swirling planet grows and pulls more and more into its orbit, and nonfiction facts suggest weird fictional possibilities for scenes, and then those scenes open up new things to learn facts about. The hard thing is not letting it get too out of hand.“

9. In “Lost and Found” and “Jeepers Jacobs” there is a dichotomy between how the characters feel inside versus how they present themselves on the outside. What attracts you to the tension between the interior and the exterior of your characters?

This seems like a common human situation, or maybe it’s especially common with middle class midwesterners? With comics also, it’s easy to pause and read thoughts, and the disconnect with the external can be played for laughs, or to give a sense of the different experiences people are having of the same world, which for me is one of the great powers of fictional storytelling.

10. You include nonfiction passages within this fiction collection. What comes first for you when delving into an idea for a comic, facts or fiction? How do they complement each other in your work?

When a story starts to form, ideas cluster around and start to spiral, like a swirling planet grows and pulls more and more into its orbit, and nonfiction facts suggest weird fictional possibilities for scenes, and then those scenes open up new things to learn facts about. The hard thing is not letting it get too out of hand. I try to read widely, and even semi-randomly, and I really love the feeling when things connect up, and books start to talk to each other, and stories grow like fractals.

Kevin Huizenga splits his time between Chicago and Minneapolis. He is the cartoonist of Curses, The River at Night, Gloriana, andThe Wild Kingdom. His character Glenn Ganges is based on his brother-in-law and the name is a reference to two separate towns that appear on the same sign on the interstate.

Remica Bingham-Risher | The PEN Ten Interview

Some of the breakthrough moments came when I decided I would be reckoning not only with my ancestress’s trauma, but also their joy, and how they raised us to understand that you can overcome nearly anything in your journey.

Maura Cheeks | The PEN Ten Interview

I was thinking about what would have to be true for someone in power to take a stand for reparations and push it through.

Kacen Callender | The PEN Ten Interview

I wanted to offer the idea that power is naturally inside of all of us, and that we can feel empowered and worthy and loved even when rejected by others for not meeting their criteria of worth.

Vanessa Chan | The PEN Ten Interview

I don’t believe you can go through a publishing journey alone, especially as a writer of color.