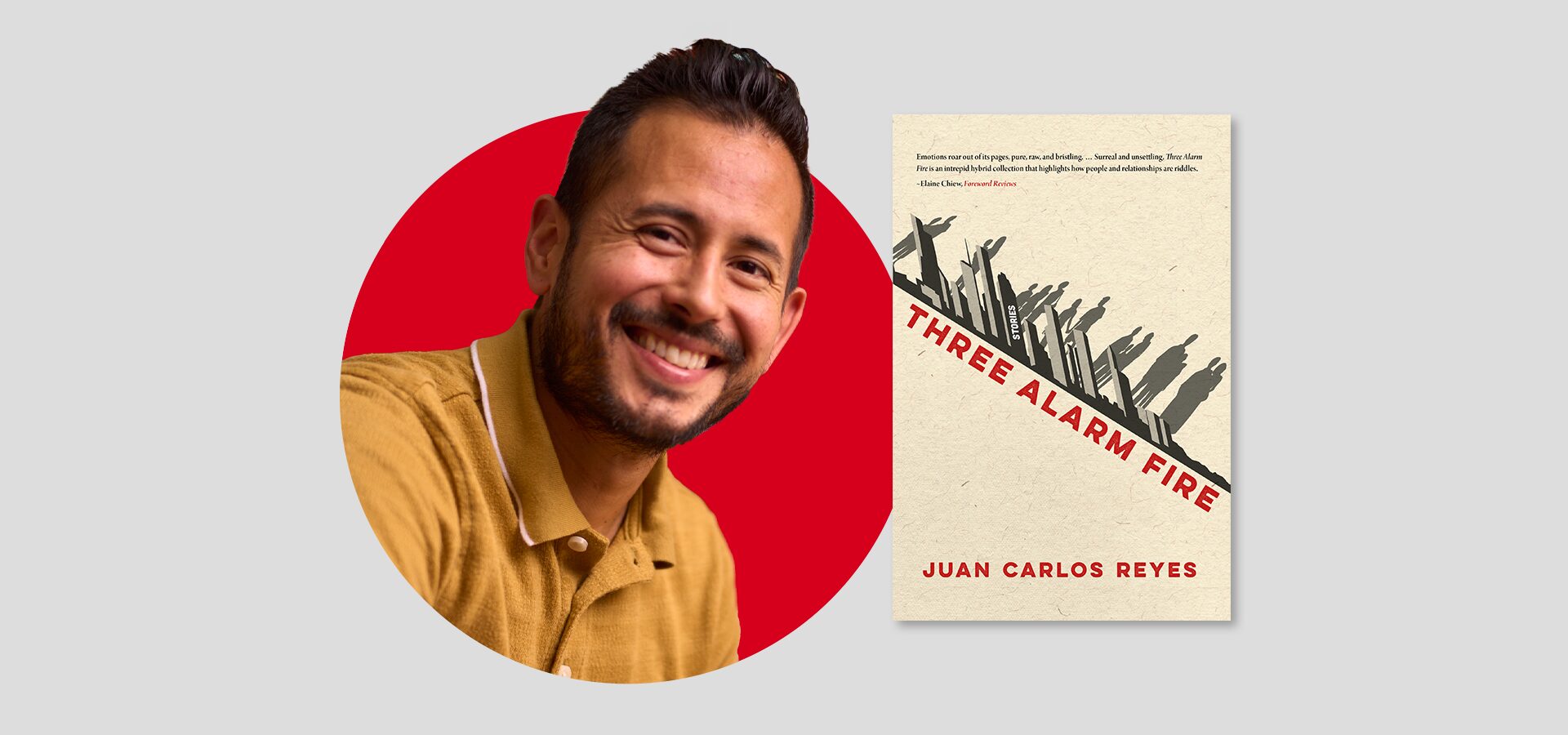

In his debut fiction collection Three Alarm Fire (Hinton Publishing, 2024), Juan Carlos Reyes assembles a diverse range of stories exploring a range of themes including immigration, family legacies, sexuality, and trauma. In fictionalized stories based on Reyes’ life, characters redefine their concepts of place as they navigate cultural clashes across generational divides. With moments that are tragic, heartfelt, and funny, Reyes’ unique collection is a reflection of how we urgently respond to the emergencies that life unfolds.

For this week’s PEN Ten, in conversation with Literary Awards Intern Maria Loo, Juan Carlos Reyes discusses his unconventional use of punctuation, giving his novella, A Summer’s Lynching, a second life, and which story was the most difficult to write. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

1. Congratulations on your debut short story collection! Short fiction fascinates me as writers can perfectly capture a story and its messaging into only a few pages. What drew you to the medium of writing short fiction?

Short fiction has suited me for so long because the characters and narrators I’ve wanted to explore have been these deeply emotional people that I could only sit with for a small window of time. I’ve gravitated to intensity in my fiction, in my writing, generally speaking, and so there’s only so long you can sit with someone in their depth of depths before you want to work your way out of it.

You could call some of the situations in this book an aftermath of sorts: here is a tragedy, here is a person who’s been through something explosive or who’s been witness to it, and here’s what happens when they try navigating through it, out of it, intact. Sometimes they fall apart. Sometimes they remain whole.

What I wasn’t interested in, however, was arriving at a resolution with these fictions. I only wanted a storytelling space in which to sit with characters as they explored decisions they felt they had to make, the rage or sadness or confusion they were trying to navigate through, even a love they would find in themselves or fail to see. I wanted to walk alongside these characters as they settled into some kind of new moment, whether in community or outside it, whether in courage or failure. I wanted to hear what they had to say to themselves and to the people around them as their next step became reality and led to the recognition of the full path ahead. And with all this in mind, I wanted to cut off these fictions not at resolution but at some even emotional line, some stable place before the next significant moment or decision. Life can feel like that sometimes, I guess, a series of experiences that reveals an insight about the trajectory we’ve been on and a truth about what might come next.

It’s these snapshots, the emotional consequences of an event, that have until now interested me the most in storytelling, and so the short story form has been fitting. Additionally, I’ve also wanted to explore some very specific craft choices in my representations of character, action, and narrative thread, experimentations in syntactical breathlessness, dialogue bypasses, and self-reflectivity, among others. And the short story has offered a contained space to be playful with all that, to experiment with textures and to learn something about what the reading experience can be like—ultimately, to craft fiction as both form and breath, complication and experience.

2. This collection contains multitudes, in both topics and emotions. What was your writing process like for intertwining each unique story into a single collection, Three Alarm Fire? In what ways do you think each story informs and compliments each other?

The intention for this collection was always to demonstrate a range of emotion and craft. I wanted this collection to feel like a musical double album—The Smashing Pumpkins’ Melancholy and the Infinite Sadness and Outkast’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below come to mind—an impression of myself as a writer that feels all-encompassing up to this point. Therefore, it was important to arrive at a title that could apply a real-world reference literally and figuratively onto the stories individually and as a whole. In the early curation of the fictions that would be included in the collection, notions of urgency, emergency, and response kept coming to mind. Additionally, as I was crafting these fictions, I imagined compiling them into self-contained triptychs, three ways to look at a situation or an idea. I fixed onto the title Three Alarm Fire early in the process, and that expression steered how I ultimately decided which fictions to include and which to leave out, and how I revised them all to better fit together.

A three-alarm fire is the first category in the multiple-alarm fire designation, and a multiple-alarm fire is a catastrophic one. Therefore, I like to imagine that a three-alarm fire is still a fire we can put out, an iceberg, so to speak, that we can steer away from if we all pull the wheel together to veer off a tragic course.

In this way, every fiction in this collection, from beginning to end, adds a next step into and out of this spiral. The first triptychs convey a kind of helplessness, the middle triptych a rage for agency, the fourth one a kind of awakening through intimacy and love, and the last one a way to reflect on it all through art.

And then we have to the novella that closes out the book, A Summer’s Lynching, a piece that illustrates this whole concept of a three-alarm fire from beginning to end. The novella is the aftermath of a tragedy, an extended fiction interested in how a neighborhood copes with the tragedy of a suicide, how they internalize what’s gone wrong with all of them, extrapolating how one person’s impulse to this final act is really a reflection of their collective impulse to cut their own lives off from everything and everyone else.

Even if the fictions in this collection were originally crafted as independent works, they complement each other in an escalation/de-escalation reading journey, the end of each story feeling like its own exhalation before the next breath.

Finally, I do want to add that the demands of publishing also fundamentally influenced how these pieces emerged in the triptych form. I don’t want to shy away from talking about the business of publishing, generally speaking, and so many of us, especially if we teach, are at the peril of the publish-or-perish compulsion. Therefore, I figured that at least attempting to publish these fictions as chapbooks, thematically or narratively interconnected, would offer smoother introductions into the world. Elements of a Bystander, for example, the first triptych in this collection, was originally published as a chapbook by Arcadia Press before the company went out of business.

Short fiction has suited me for so long because the characters and narrators I’ve wanted to explore have been these deeply emotional people that I could only sit with for a small window of time.

3. There is a consistent use of commas instead of quotations for dialogue. What influenced this creative choice? What was your intention?

Yes, there are almost no quotation marks to distinguish dialogue. This was an intentional choice to experiment with a reader’s expectations of a conversation in a book and a writer’s expression of continuity of craft.

The comma reflects a breath we should take when reading, even if it only feels like something of a half-beat. The period is that full beat before the next breath, an understanding that what we’ve arrived at is the end of a partial thought even if the train of thought continues afterward through narration or dialogue.

That said, I wanted to overturn these conventions, these expectations of reading that often look like someone breezing through a page to get to the next. When I read, I often sit with a paragraph, with an excerpt, with a page, for a while. I’m a slow reader, and I enjoy that. So much about the choices I make in my work is to encourage that sense of pacing in others. Like, let’s sit with these ideas a bit longer until we feel them reflected in some tangential thought of memory; let’s sit with these characters a bit longer until we feel their complicated humanity reflected in something within or around us.

These craft choices demand a slower reading pace, and this is very much my way of intentionally interrupting how we engage with media, generally, how we understand, for example, something like a news feed, the tragedies and emergencies and reports of the figurative and literal fires embedded in all our sources of information and stories: the genocide in Gaza, modern-day slavery in metals mining, our drying rivers, January 6th—we get rained on with so many snapshots of disaster, and even as it’s important to know about all of it, let’s slow down with it and understand a moment within these macroscopic reports of tragedy and sit with, hear from, walk alongside someone having to bear the brunt of that disaster: a child who lost her parents from a bomb, a father whose hands have become irreparably contorted from the cobalt he’s had to mine to provide barely a day’s meals to his family, the cautious negotiators of a water crisis on the Colorado River whose hands are tied by policy and red tape, the Capitol Hill officer permanently injured by the mob incited by the former president. The forms in which our news appears, this formatting of hurling all this data at us, all this text and information, can make us immune to the emotional and psychological toll of those affected and our own desensitization, an emotional and psychological toll of its own: we’re these distant observers made to feel even more distant by the speed in which we receive all this news.

All this to say that the choices I’ve made in this book, and that I make in all my work, is very much a reflection of how I hope to engage with media myself. I don’t just want to consume it; I want to have a whole engagement with it, and so I craft my fiction and my characters with that sense of experience in mind.And then again, poetry doesn’t simply supplement the rational intellect, but provides inherently and sometimes incommensurable forms of insight. Because its meanings are neither quantitative nor verifiable, poetry may offer different, subtler, and more complex expressions than the language of science and commerce. As Ludwig Wittgenstein noted, “We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have not been touched at all.”

4. The story “SYG” hones in on the cultural clash in interests and values between The Son (a second generation American) and The Father, who immigrated, a struggle every first-generation child knows all too well. This story mainly focuses on “family” and what it means. What did family mean to you growing up in the United States? Has this changed throughout the course of your life?

Firstly, I want to give props to poet Jason McCall whose poem “SYG” is the reason my fiction even exists. I went through a few years when I was writing short fiction inspired by and in response to poems I enjoyed, poems by poets who also happened to be friends. There’s more than a handful of short stories I wrote this way, only two of which appear in this collection. (The other short fiction, “Drown,” is inspired by and responds to Abraham Smith’s series of poems “Dear Weirdo.”)

“SYG” is the acronym for “Stand Your Ground,” that infamous expression applied to lax gun laws that allows someone to shoot someone in “self-defense” if they “perceive” a “threat.” (Everything in quotes seems to be up for legal interpretation, but I’m no expert.) McCall’s poem meditates on blackness and masculinity, on pride and history, on all these ideas and physical manifestations that converge upon a moment of profound helplessness and fragility.

I contemplated that poem for a long time after reading it, wanting in the end to respond to it in a way that felt culturally fitting for me. I tinkered with narrative style and characters, throughlines and scenes, for a long time. I even went beyond my wheelhouse for a while, crafting a story that used quotation marks (but without dialogue tags) and fragmented sentences to articulate this sense of a community’s members interchangeably cutting you off from the world. (I also want to give props to the Jack Straw Writers Fellowship, as it was that cohort of artists and writers that received early drafts of “SYG” and helped me process its meanings.)

Eventually, the more I tinkered with the character’s voice, with the narrator’s style, I arrived to a sense of contraction and expansion of language and detail that helped me craft quite the variation of tone from beginning to end. For starters, I allowed the story to shift from third person to second to first to purposefully model how this young man, initially overwhelmed by his family’s expectations, begins to distinguish what he wants for himself from what he can offer his family. Each of these sections comes with its own syntactical forms to reflect introspection and interaction, dialogue and self-talk. In the end, the protagonist never really arrives at a place of complete independence, but I also don’t think the character was looking for that in the first place.

Culturally, there’s something beautiful about that lasting interconnectivity to family, that weaving of their highs and lows into your own life even from a distance. It’s that interconnectivity that feels like culture to me: the relatives that I grew up with are my reflection of culture, all of us arriving to the United States in waves, first one decade and then the next, and settling in West New York, NJ, a gritty town that still remains a focal point of immigrant experience in the northeast, borrowing so many characteristics from its namesake across the Hudson River.

For a long time, we all lived within a few blocks of each other, and childcare reflected that reality: aunts and great-aunts were our second mothers. Eventually, we all started spreading out a little bit more widely and, ultimately, to all corners of the U.S.: Seattle, Dallas, Orlando, Chicago, etc. So many of us cousins, however, were raised like siblings, and being immersed in our turbulent and often aggressive hometown created a deep relational richness between us. Whenever I feel lost in and even confused by this category “Latino/x” or “Latin American” or “immigrant,” largely because its meanings and implications still feel so big and unwieldy to me, I take comfort in my family, my relatives, as my one lasting definition of culture. Sure, as kids we were all our own versions of teenage rebellion, which very much reflected in the different choices we made to create a space for ourselves. But even as I’ve arrived into my own life’s settling of form and place (my wife and my two children now being my immediate center), my center is also a radiating one, always containing my parents and my siblings, my cousins and my aunts and uncles, my friends and my extended community.

This, ultimately, has been the lasting impression of my childhood, this everyday closeness with an extended network of people, all of it reflected by and based on a tangible sense of trust.

5. This short story collection identifies cultural tensions with sincerity and humor. Is there one story in particular within Three Alarm Fire that is closely inspired by your lived experiences? If so, how have your lived experiences fueled your writing in this collection?

Where do I begin? So many of these stories are indeed compilations and fictionalizations of various life experiences and the experiences of those close to me.

From the first short fiction in the collection to the novella that completes the book, the settings are based on towns and cities dear to me; the moments these characters share with each other are familiar to me; their personalities and frictions and situations and responses to the world feel like small reflections of anxieties, hopes, confusions, joys, insecurities, and an admiration of things that feel known to me.

Of all the stories, though, “Warrior, New Jersey” feels like the closest fiction to me, though even that one is a swirl of histories not so much blended together as arranged to fit like a salad.

On the one hand, the piece considers the cultural tension of where we come from, which in the northeast, even if you’re an immigrant, begins with the place you grew up in last: New York, the boroughs, Long Island, Jersey, the city, the sticks, etc. This has always felt so funny to me because every five blocks where I grew up in West New York always felt like another village of nationalities, of ethnicities, of a new set of flags. The town was, still is, a congested, hard-grinding kind of a town of Latin American, and increasingly Middle Eastern and African, immigrants. Most days, you only need Spanish to get through some kind of daily routine; so many people still carry nationalistic tendencies from their birth countries; and I still have this cognitive dissonance with my upbringing there in the 80s and early 90s. As my cousins have often put it, “We’re alive, right?” and I have to laugh at that because as a kid, I couldn’t have imagined a different childhood from the constant vigilance and tension and fragility of all things. It wasn’t until my mom, on the back of a scholarship and a work study program, sent me to a prep school in Jersey City that I really saw the Jersey that pop culture more often referred to: kids from suburbs where monoliths and sameness governed more of the day, this middle class and even working middle class consortium of white people that I must have been an alien to, because I certainly looked at them like they were aliens. It’s this central tension that underlies “Warrior, New Jersey,” something that compels the central characters, a pair of undergrads, to come together: assumptions others make of them because they’re from Jersey, though from very distinct parts of Jersey, put them into a stance against everyone else.

These two characters notably also gravitate to each other because of this unspoken softness between them, a gentle landing in each other’s presence. One thing leads to another, and the whole story is this slow build that ends when the space between them disappears, this moment of recognition that something had been unfolding the whole time: their comfort with each other had bred a familiarity that had bred a trust that had bred an affection that had bred a possibility until the air between them thins to nothing.

Much of the way I craft my fiction is intentional in this way: a character feeling defined by their place and circumstances, pushing at the boundaries to see what cracks and what doesn’t, and then falling into or finding a way to creep out of this desperation.

6. In “A Summer’s Lynching,” the collection’s final section, each story is marked by its surroundings, with titles like “The Ambulance” and “The Police Department.” With a detachment from the characters and unusual names, this section is surrealist in tone and subject matter. Each story is framed like a looking glass, as if the reader is peering into these spaces. What made you want to write stories that captured odd moments in these spaces? Are there distinct places you go back to in your writing?

A Summer’s Lynching is a novella, all its parts tie together to consider the aftermath of a suicide, in this case a war veteran’s suicide. The novella many years ago won the Quarterly West novella contest, and with it came an honorarium and 125 copies, and so it fell on me to spread word of the novella. However, my family and I were in the process of relocating to Seattle that year for my teaching gig at Seattle University (where I finally received tenure last year), and I had been working a second job for most of that year, moonlighting as an interim director of the Stetson University MFA of the Americas, and I was, well, really tired. Moving, a new job, and the busy weeks and months of adjusting to a new place was an emotional rollercoaster. All that to say, I had no wherewithal or energy to support the book, and even with the positive reception for those who engaged with it, it remained largely my own little gem.

And then this opportunity with Hinton came around many years later, and while negotiating the contract with them for Three Alarm Fire, they were the ones that convinced me that the novella needed—wanted—a second life.

The novella is, indeed, partitioned into these chapters that for the sake of the novella I call loops, thirteen of them, shaped by the thirteen loops of a lynching noose, this old form of American violence as much about a threat as it is about the execution of a final act. The structure was partially inspired by B.J. Hollars’s book Thirteen Loops, the story about the last lynching in America.

Each loop in A Summer’s Lynching does, indeed, consider a different setting around this fictional town, largely based on the geography of the corner of West New York where I grew up. Each loop is somebody else in the neighborhood, a new point of view shaped by their immediate setting (the church, the public library, the high school) and trying to articulate what increasingly becomes a disentangling situation, a whole part of town falling apart and coming onto the streets because they want to know what happened to this man who killed himself, why he did it, and even who did it, because through hearsay and rumbling on the street, more and more people start to believe there’s some collective blame to be passed around.

Every space, every setting, in the novella is a generally common space but made to feel uncommon and even, yes, odd, by the arguments and rising tensions between characters who are all kind of just losing control of their beliefs and disbelief, this ever-growing feeling that they can’t really trust their own intuitions anymore, that they can’t really trust each other anymore.

So much of the way I craft my fiction is intentional in this way: a character feeling defined by their place and circumstances, pushing at the boundaries to see what cracks and what doesn’t, and then falling into or finding a way to creep out of this desperation that comes when you try to put words to something only to feel more confused by the language you hear reflected back at you.

7. Out of all the stories of this collection, which one was the most difficult to write? What advice do you have for writers to maintain momentum in their writing?

The last short fiction in the collection (the one before the novella) was the most difficult one to write. Originally, it wasn’t even supposed to be included: its original version didn’t feel like it fit into the working concept of the collection. And then when alternative pieces also weren’t working, I kept coming back to this piece called “Review of a Last Act.” Now, this whole section of the collection, “The Reviews Are In,” which you reference in your next question, was supposed to feel more lighthearted, more tongue-in-cheek, than the fictions that came before it. But I discerned through many bouts of revision that my initial impulse was wrong: I needed, in fact, to return full circle to the tone of the book, to find a short story that would offer a proper tonal end to the short fictions.

And so, as I mentioned, I kept coming back to this piece I’d drafted and revised years ago which never really worked then but which I needed, very importantly, to work now. So I got to work on it, cutting and rewriting, cutting and rewriting, etc., following that cycle while alternately falling in love with the piece and then hating it, until the fiction started coming together little by little.

The narrator in this piece is the same narrator I’ve used before, in other unpublished pieces (and in the story “Review of Sitting Down” also included in the collection), a character that feigns to be this social critic, or at least trying not to be a failed op-ed writer, who looks at everyday things and imagines them as somebody’s “performance” which demands a review of their performance. Basically, this narrator is a tonal blend of a Yelp reviewer and a theater critic.

In “Review of a Last Act,” this narrator takes his pen to the “performance” of a conservative church group protesting the funeral of gay military service members, and he treats the protestors like a band who’ve been around for a while, who have put out a few very niche “albums,” and who have just lost touch with the world—or, as he assesses, might have never really been in touch with the world at all. What felt important about crafting this piece is that I wanted to diminish the attention on this church group and shift more attention to the minister officiating the ceremony at the cemetery, a clergy member who goes “solo” because he wants to get back in touch with “the music.” Because I had a very clear vision for the ending, which I don’t usually have, I took pains to craft the piece with all these necessary turns to get to the end without making the whole piece feel too artificial—even if, in the end, all fiction is artificial, nothing but a narrative frame to deliver our stories in a formed and formatted language that feels accessible and familiar to a reader, whoever we imagine that reader to be.

In any case, I’m not sure I can reiterate enough the hours spent on that piece which likely isn’t even finished but which I offer here as a way to say “at least as of now, this is what I imagine the piece to be.” And that’s really the insight I can offer, if we can even call it insight: if we’re really paying attention to everything we’ve read and everything we’re going to read, it’s all flawed, it’s all imperfect, it’s all broken and unfinished in some way. So why not explore a piece you write, something you craft, with a lens for breaking it and making it feel like just simply a beautiful mess.

8. In Three Alarm Fire’s fifth act, “The Reviews Are In,” one of the reviews is surprisingly about the collection itself, making a jarring metareference. What inspired you to choose this story? How does it address the audience directly, if it does?

Writing fake reviews of my own work is something I find quite enjoyable to do, largely as a way to work through my own anxieties of completing a manuscript and what may or may not be working with it.

The first time I attempted anything like it was actually for the novella A Summer’s Lynching, many years ago. I was still in the middle of revising the manuscript, and I had been reading a flurry of novels by Laird Hunt. There was a striking similarity of tone between what he has going on in his work and what I thought I had going on in my work, and I took some time away from revision to imagine what Laird Hunt would say about the novella. But it also eventually got a little weird: I crafted this fake book review of my novella from the point of view of my version of Laird Hunt navigating a world tonally similar to the ones he’s written in search of the book review about my novella that had been stolen from his apartment. He slowly finds clues left like breadcrumbs around the city until he finds his way into a tax office with accountants clanging away on their typewriters, all of them typing up some version of the book review. The fake Laird Hunt has to compile all these pieces into a single opinion of the novella while also trying to figure out how to escape the storefront as the walls start closing in.

Strange, I know. But the strangeness of it all was importantly my way of coming to terms with how the tone of my novella came together, what inspired me to craft the settings and characters the way I did, and, ultimately, to articulate how much I enjoyed this sense of spiraling in my work, characters revealing themselves and the word around them in swirls of dialogue and setting and action. Very importantly, too, the fake review was my way of anticipating questions I believed readers would have of the novella, so when I needed to finalize the pieces that would eventually go into Three Alarm Fire, I went ahead and wrote a fake book review about the collection. There were questions I had already begun to get from the publisher about Three Alarm Fire, things like “Why did I curate these particular stories for the collection?” and “What reading journey from beginning to end did I want for my readers?”

I wanted to feel like an outside observer of my work again, and so I chose Salvador Plascencia this time as my writer-muse. I so thoroughly loved his novel The People of Paper because structurally and visually the text felt like this beautiful mess that wove together like a smooth piece of paper. In this fictional book review for Three Alarm Fire, Plasencia the narrator is trying to write the book review by having conversations with other writers who have also fake-read my fiction collection, these sit-downs-over-coffee that help Plasencia the narrator come to terms with what his own opinions of the book even are. Partially, this was my way of playing around with this notion of influences in my work, how my influences find a way not only into my craft but also into my points of view about crafting fiction. The conversations that Plasencia the narrator has, of course, get into the weeds about all kinds of things, including an assessment of the state of Latinx literature and a reflection about the communities we have made by the books we have read. Because of my last name, I have never been able to undercut this subtle and explicit expectation in the literary community of what I should be writing. Part of what I wanted to make clear is that Latinx literature is a whole new environment than it was twenty or thirty years ago—even ten years ago—and so there should never be any expectation about what we should or shouldn’t be getting our crafting hands messy with.

This was part of the direct messaging to readers. Crafting fiction is fun, reading is fun, and both are a wonderful experience. I hope this book, if it does nothing else, contributes to the idea that this relationship we create with readers begins with the experience we have with our own work and extends into the experience of that work when it’s in someone else’s hands, physically or digitally.

9. How does Three Alarm Fire navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Hernan Diaz’s reflections on fiction’s dispositions to truth was so influential in the revision process for this book. Diaz has this essay called “The Heart of Fiction,” based on a lecture he gave at Yale University. In it, he considers these dispositions to truth which, if I’m summarizing completely (though I doubt I am) is in part based on the narrative frame of the book, on the narrator’s own relationship to this frame, and on the form the story and characters take as a world unfolds on the page. And the quote from that essay that remains with me, as it did while curating the fictions for this collection and revising every piece in it (which, in the end, could always use more revision), is that “fiction, rather than presenting us with truthful content, shows us how we experience truth.” And that’s what I wanted every narrator in this collection to embody as thoroughly as I could embed it: the notion that our experience of truth not only varies from person to person but is always engaging these cycles of meaning that phase in and out of haze and uncertainty, that claim a truth from what we can extrapolate from the life of an experience that begins with the senses we rely on the most and which leave an imprint on our bodies, a memory we don’t always have a language for. These narrators are all caught up in some trying times, some cagey times, some intimate times, some funny times, and I wanted them to explore themselves and their moment for what their senses tell them feels important or disappointing or unreliable or clear or anything else. I resisted letting the text feel too certain: certainty can often pass as “truth” in fiction, and I didn’t want much part in that. In this book, I didn’t want truth to look like conclusions. Instead, I wanted the truth a character experiences to simply be the life of the moment itself, the process of feeling one’s way into and through the aftermath of an experience, one nerve-racking sentence at a time.

So many of these stories are indeed compilations and fictionalizations of various life experiences and the experiences of those close to me.

10. What do you hope people gain from reading Three Alarm Fire?

I love the trail of these questions because their answers really have led us straight to articulation of this final answer. I hope readers embrace the reading experience of this book, in whatever shape that takes. I hope readers enjoy these fragile, fun, messy narrators and characters, that even when it feels difficult to go on, readers embrace the sounds of these people, their eagerness and breathlessness, their need to feel heard.

Juan Carlos Reyes has published the limited-print novella A Summer’s Lynching, winner of the Quarterly West 2017 Novella Prize, and the limited-print chapbook, Elements of a Bystander, winner of the 2018 Arcadia Press Fiction Chapbook Prize. He has received fellowships from the Alabama Prison Arts & Education Project, the Jack Straw Cultural Center, PEN USA / PEN America, and the WA State Artist Trust.

His first full-length fiction collection, Three Alarm Fire, is forthcoming from Hinton Publishing, October 2024.

His short fictions and essays have appeared in Florida Review, Waccamaw Journal, and Moss, among others. He is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Seattle University and has served on the board for UNESCO Seattle City of Literature, an organization that works towards equity and sustainable development by mobilizing the literary and arts communities.