In the fall of 2021, I was researching the history of library services for incarcerated people in the ALA (The American Library Association Archive). Much of the work was rote—digitizing files for future engagement—but having my hands on the actual documents increased my feeling that the work I do occurs within a lineage of efforts by librarians. I was often hung up on the traces of humanity I encountered in the records and on the notable absence of recorded engagement with people who were incarcerated.

In records from the early 1990s, I encountered one letter addressed to ALA that countered this trend. That letter was from Patricia Prewitt, a woman incarcerated in Missouri. She described her day, emphasized the importance incarcerated people place on books, and emphatically asked that ALA not forget about incarcerated people.

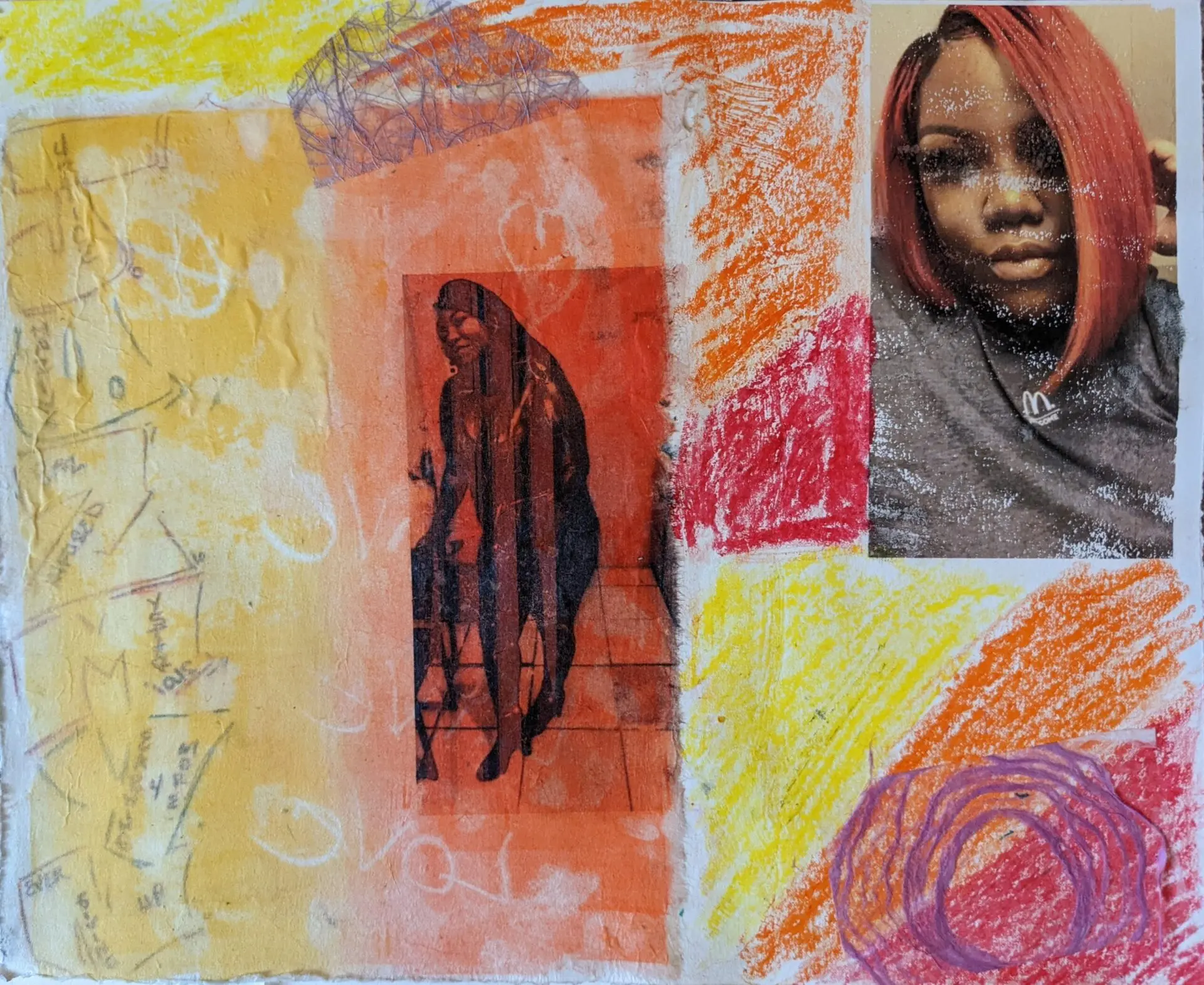

Moved by the letter, I checked the Missouri locator to see if Patricia was still incarcerated. Some 15 years later, she was. I reached out to her, and we have been corresponding, typically monthly, since. During our correspondence, she has moved to another prison to enter an education program, to her great joy! More recently, the state of Missouri has moved to digitize all incoming mail, to my professional and personal chagrin.

Patricia, who goes by Patty, agreed to have our interview about book access published. The interview itself was conducted through the mail; my letters were mailed to a company in Florida that scanned them and sent a digital copy to the prison where Patty is located, where the scans were either printed or available through heavily restricted technology (tablets or kiosks), hers came to me in physical form, written in her characteristic cursive and signed with her characteristic drawing of a smiling sun. I’ve transcribed our interview for publication.

Jeanie Austin: Will you please introduce yourself and let us know what you like to read?

Patricia Prewitt: I’m an elderly lifer who’s served over 36 years for my husband’s murder in 1984, although I did not kill him. My prison sentence is LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE FOR FIFTY YEARS. I will be eligible for parole in 2036 when I’m 86.

I like to read anything worthwhile, but memoirs are my favorite because I’m nosy. I’m currently enrolled in the Prison Education Project at Washington University in St. Louis, and those classes keep me VERY busy!

JA: When we met, you told me it was difficult to get access to a dictionary—how long had you been trying/hoping for one?

PP: For years (decades). To access a dictionary, I had to go to the library, which is extremely inconvenient.

JA: Are there other books you would like to access?

PP: Since I enrolled in Wash U in January, I’m fortunate to be in a Book Club with them, but I see books in news magazines, like The Week, and on TV that I’d love to read. We can only have 6 books (personal) in our possession, and the officer counts my poetry publication as a book. I tried to explain “periodical” to her to no avail. She counts The Massachusetts Review as a book, too. It’s so frustrating!

I’ve taken correspondence courses over the years, and although the textbooks are not supposed to count in your 6, I’ve had certain officers refuse to allow me to have the textbooks because I already possessed 6 books. Arguing with corrections officers is harmful to your health.

JA: Have you ever been told a book you want isn’t available or allowed within the prison?

PP: Yes, certain books are NOT allowed. Someone sent me a book about Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, MO, and I was told I couldn’t have the book. I told the officer that I already knew he was shot down for no reason by the city cop. The story was big national news, but I was not allowed to have it.

I never tried, but Fifty Shades of Grey is not allowed even though the movies have all been on TV. We can have nothing sexual. No Dean Koontz and most Stephen King are banned. It’s CRAZY!

JA: Policies change. Have any changed in ways that have made it easier to get books? Have any changed in ways that make it more difficult?

PP: For decades, we couldn’t have hardback books, even though there are hardback books in the prison library—but that changed a few years ago. The Property removes the dust jacket and throws it away—even though the books in the library have dust jackets. Again—CRAZY!

JA: What kinds of restrictions do you face regarding keeping books or papers? Can you share books or donate them to the library?

PP: We share books, but it’s against the rules. You’ll get a conduct violation if caught. We cannot donate books. We have to mail them out.

We’re supposed to have no more than a couple of inches (thick) of pages.

JA: Is there a library? Is there a librarian?

PP: We have a small library and one MEAN librarian. There is also a small law library in the back, but research is terribly restricted.

The rules are only a handful in the library at a time and only for 10 minutes. Girls run when OPEN LIBRARY is called, line up, hope to get in, and if they do get in, they grab a couple of books Quickly! It was even worse during COVID restrictions! Oy vey!

JA: Anything else you’d like to add?

PP: The computer in the library has been down for weeks, so no one can check out any books. This is RIDICULOUS for a prison!

JA: How can readers support you?

PP: Readers can support me by checking out pattyprewitt.com and signing a petition or contacting the Missouri governor in favor of clemency for me.

JA: How can readers support more access to librarians in prisons?

PP: This question is complicated. Prisons are rigid and mean. Wardens don’t care about libraries. A company named Securus gave all Missouri prisoners tablets with podcasts, games, etc. on them. Most wardens think that’s enough and don’t trust books because liberal ideas may be in BOOKS!

Post note: As Patty makes clear, there is a clear desire incarcerated people have for information—one that motivates people to take risks just for access. Connecting directly to incarcerated people, to education programs like the one Patty describes at Washington University, to librarians working with incarcerated people, or to community-based groups like Books to Prisoners are ways that any and everyone can help to increase access to books and support prison libraries.