Poetry, with its ability to distill complex emotions and experiences into evocative language, serves as an impactful medium for both personal expression and community engagement. For some, poetry provides a method of exploring and articulating innermost thoughts and feelings; for others, it allows them to connect to people despite physical boundaries of separation. Lars Gunther Parker, who first turned to writing while in a Maximum-Security isolation cell with no human contact following the death of his parents, considers how writing enabled him to confront his deep pain in a healthy manner: “While in isolation, I had to learn how to cope with my emotions in a constructive way rather than through hurting the world around me.” Regarding his personal experiences with writing, JA Davis explains, “For me, poetry is neither compensation nor revenge. It is a chance to participate in what feels like the truth. To deliberate (while de-liberated) on the essential confrontations of man is to rally against indistinction and blurring. It is a rare, instructive relief.” On his own relationship to his craft, Jason Centrone notes, “As writing continues to grow personally in its roles as expression, as discipline, a learning tool—how I figure pieces of myself out—abiding ones, emerging ones, but too, old hurtful, selfish quirks—ones I have to nearly drag onto the page, I feel increasingly closer to the craft, more respectful toward it even.” For Ken Meyers, poetry also provides momentary solace during his incarceration. He writes:

I’ve always thought of poetry as a compact and portable art form suitable for confined spaces, and now it has become a metaphoric echo of my former life as a wanderer. Poetry is my bivouac, the shelter I erect against the prison elements and storms that batter me. It is my backpack holding what I need to survive, a welcome burden, sometimes chafing and always needing readjustment. It is the road I once wandered that allows me a few moments unconstrained by the wire.

As these writers suggest, poetry can cultivate spaces of healing, creativity, and meaningful change. The National Poetry Writing Month (NaPoWriMo) project gives writers the opportunity to do just that. In 2003, inspired by the National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) challenge of writing 50,000 words of a novel throughout November, poet Maureen Thorson began crafting one poem a day during the month of April: National Poetry Writing Month. Thorson shared her writing on her online blog, and soon connected with other writers who also took part in this initiative. The NaPoWriMo project has since brought thousands of aspiring and professional writers together to complete the challenge of writing 30 poems in 30 days.

Each year, the Prison and Justice Writing Program contributes to this project, inviting incarcerated individuals from across the country to join the challenge. We send initial prompts through postal mail, and check-in throughout the month with additional materials, including craft talks and essays from various writers. The goal is not to craft perfect poems, but rather, to foster a healthy, daily writing practice and routine.

Completing this challenge looks different for each person, and reasons for participating varies. When describing the importance of this project for incarcerated writers specifically, Centrone writes:

A strange truth concerning facility-life is that there is no expectation for us to do anything here, or be anyone. If someone struggles with motivation, they’re able to pick up a “Duster” job on the unit and settle into the TV 18 hours a day. Having an “assignment” like NaPoWriMo can add a little pressure to get focused—to crack the binding on a composition book.

Meyers approached NaPoWriMo as the “assignment” Centrone mentions, remaining steadfast in his writing practice daily:

I dedicated a notebook to the project and first thing every morning (some days when my cellie left for work at 4:30 AM, others after 6:15 AM count), I sat down and tried to answer the day’s prompt. Some of the prompts spoke to me immediately, like the Day 1 prompt about lunch in a cafeteria, inspiring “Mainline,” a reflection on the days when we used to go to the dining hall, a process that ended with COVID and never resumed. At the opposite extreme, the poem, “NaPoWriMo,” has nothing to do with any of the prompts, but as soon as I saw the acronym, I also saw the chemical symbols and thought there must be a poem there. It took a while to work out what it would be, and I ended with the question I started with: “but what the hell is ‘ri?’”

Parker engaged in the challenge as a way to document his experiences, both mundane and uncommon, while incarcerated. He specifically discusses the inspiration for one of his poems—witnessing a total lunar eclipse from prison:

Even though I am incarcerated, I still wanted to witness this historic event like many others throughout the United States. But, I could not because I was ordered to lock down, due to the prison administration’s “fear” of inmates looking up into the sky and burning out their retinas. I remember feeling amazed when I saw all the staff pass out solar eclipse glasses to one another so they could go outside of the guilds and have a watch party. My peers and I had to remain locked down and watch the Eclipse pass over on our TV screens—that is, if we had one in our cell of course, which not everyone did. We couldn’t exactly see out of our windows due to them being glazed over from the outside with paint in order to obstruct our vision. When the total eclipse finally passed overhead, I could see the shadows in my cell grow heavy and feel the temperature drop. Later that night, when things went back to “normal” within the prison, I went to church. When I got back, instead of remaining in the guild, I went to my cell to be alone. It was during this moment that I wrote the poem, “Indoor Weather.”

Perhaps the most meaningful component of NaPoWriMo is the community that grows from it. Even though the majority of participants are unable to see or communicate with the other writers, each person knows that they are not alone, that there is a whole group of people, on both sides of the prison walls, responding to the same prompts and writing alongside them.

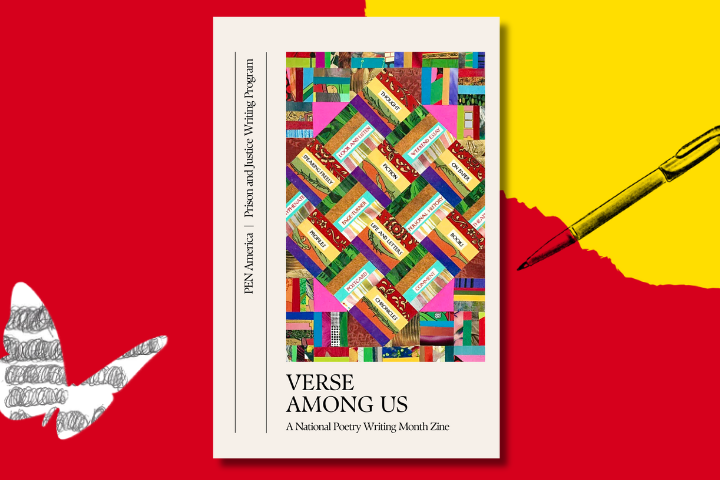

This zine itself is a communal space, where writers—separated from each other by state lines, and from society by fences and razor wire—share their poems, and in turn, contribute to a cohesive project. The writers within this zine have various creative backgrounds, from seasoned authors to aspiring poets who had the courage to pick up the pen and try the challenge for the first time. They crafted poems of many different subjects and themes: nostalgia, longing, loss, love, dreams, survival. Even the cover art, created by incarcerated artist Jeff Elmore, reads as a poem, its metapoetic words against a backdrop of intricate visuals.

NaPoWriMo is much more than a 30-day poetry challenge. By engaging writers creating from carceral facilities—spaces that are immensely isolating, oppressive, and demoralizing—our hope is that NaPoWriMo enables them to experience a sense of connectedness, solidarity, and perhaps even beauty. Let the poems in this zine be a testament to the resilience, creativity, and radical transformation that occurs in spite of prison walls, and an illustration of the community strung together by the verses among us.