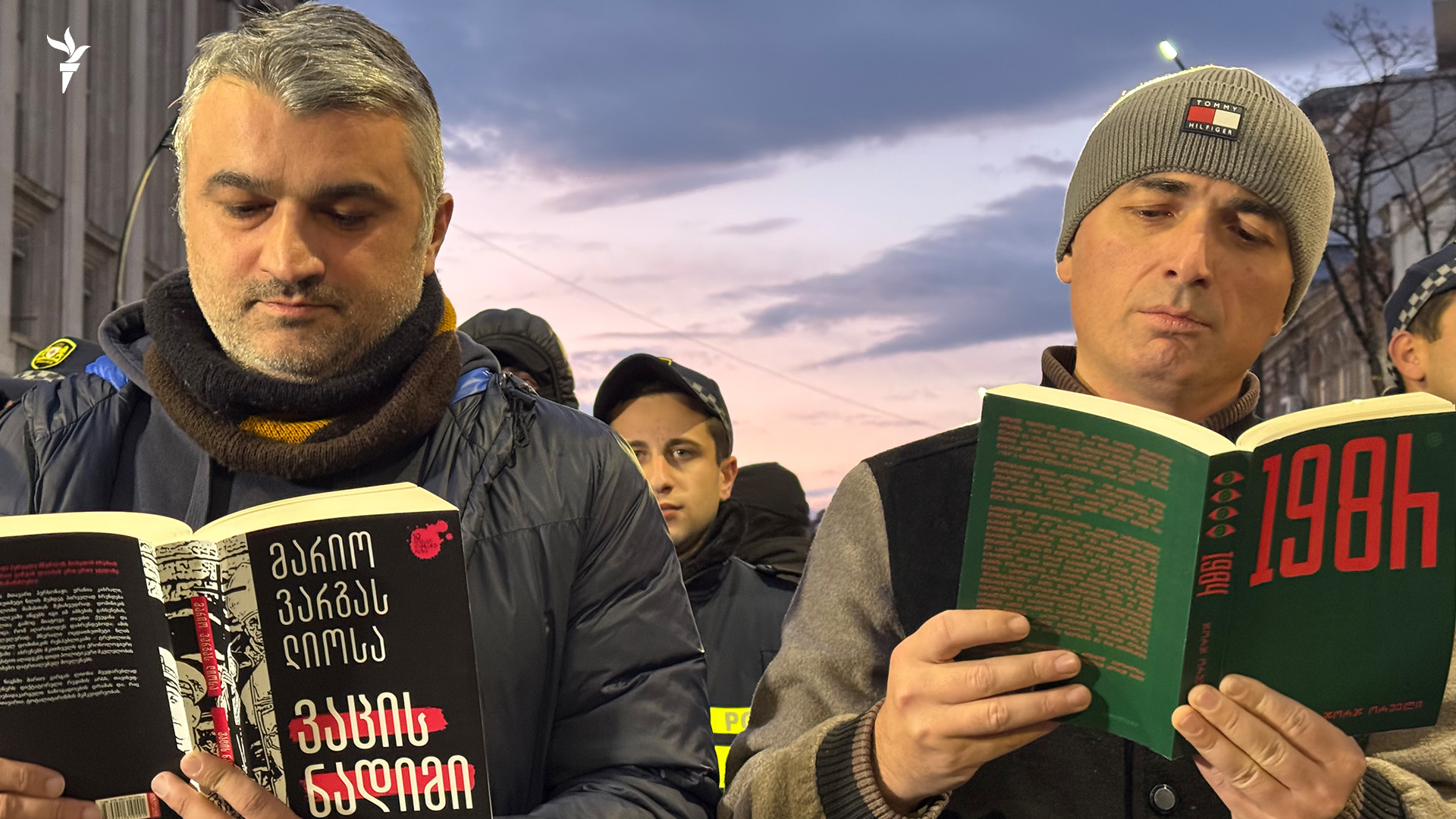

On November 28, a month after crucial parliamentary elections in the country of Georgia, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced the suspension of talks to join the EU until 2028. Since then, thousands have gathered in protest. Writers have read George Orwell’s 1984 in the streets, poets and translators have been arrested, and journalists have been beaten and jailed for reporting. This comes after years of warnings of democratic backsliding in Georgia, as highlighted in our report Taming Culture in Georgia, released a little over a year ago.

As demonstrations in support of democracy, free expression, and human rights continue in Georgia, writers find themselves playing a critical role. The following essay by Paata Shamugia, a Georgian poet and former president of PEN Georgia, provides a writer’s valuable perspective on the struggle ahead and the importance of solidarity.

Today, as thousands of Georgians again take to the streets to protest what they see as electoral manipulation and pro-Russian policies, the world witnesses another crucial moment in Georgia’s enduring struggle for democratic values.

Writers have always been on the front lines of these battles. I can hardly recall a protest where the voice of a writer wasn’t prominent. In Georgia, during the collapse of the Soviet Union, writers were at the forefront, and as a result, a writer even became president. This current protest also would not happen without writers.

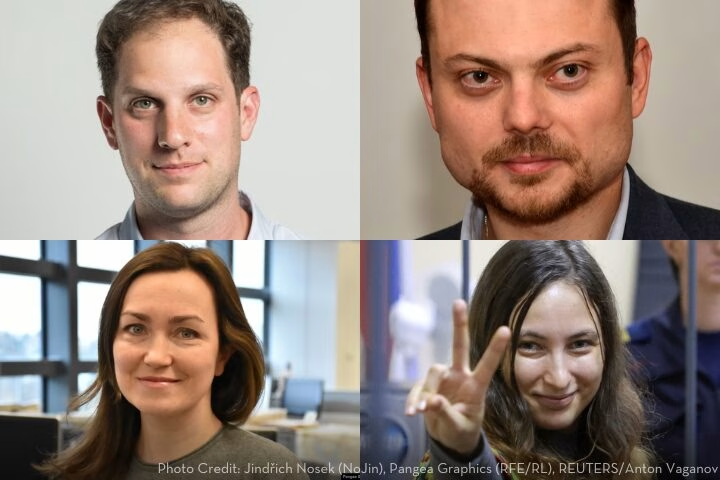

These protests were preceded by some of the largest demonstrations in Georgia’s history, led by poet Rati Amaglobeli and former poet Beka Qorshia (he calls himself a former poet, though we have a saying in Georgia that there are no former poets or former KGB agents). Many of my colleagues and I were compelled to be spokespersons for these demonstrations and speak on behalf of the writers.

As a result, three writers were severely beaten and tortured during their arrests: Zviad Ratiani, Tornike Chelidze, and Data Kharaishvili. And we have around 300—a number that increases daily—individuals who have been tortured because they protested against the constitutional coup, the imposition of censorship, and the violence of an oligarchic regime.

When I say “tortured,” this is not a poetic metaphor. “Fracture of the fifth vertebra, fracture of the occipital bone and septum, hematomas of varying severity, and contusions are observed in living beings.” This is the official medical report regarding the injuries of poet Zviad Ratiani; and this is not even the most severe report issued by doctors after examining hundreds of injured individuals in recent days.

Despite all this, the court left Ratiani in detention for eight days with these injuries, even though the doctor stated that he should not be detained for even eight seconds. But who cares about that? The dictatorship must be protected!

The ongoing protests represent more than just domestic political discord. They embody the fundamental choice facing Georgian society: whether to continue its path toward Euro-Atlantic integration or risk falling back into Russia’s sphere of influence. The demonstrators’ demands for fair elections and democratic reforms reflect the broader aspirations of a people determined to secure their place in the community of democratic nations.

However, all of this is hindered by the state’s own repressive apparatus, which at times enacts homophobic laws, at others legalizes censorship, and sometimes does both simultaneously. It is clear that these laws represent an evil that guarantees only one thing: marginalized groups will face even greater oppression, and censorship will spread across all areas of life.

It is evident that, since propaganda is primarily executed through words, censorship will first and foremost target the places where words live—literature, academia, and journalism. But censorship, in one form or another, will affect not only literature but everyone and everything. In academic institutions, for instance, a literature lecturer may be forced to remove Boccaccio’s The Decameron or works by Georgian authors from the curriculum. Publishers might be compelled to cancel the circulation of books by “dangerous” authors. Cinemas will be unable to screen “corrupting” films. And in schools, subjects about culture will be removed.

Thus, the battlefront is multifaceted, and on this multifaceted front, we need the support of those who share our values and stand in solidarity with us.

We have no illusions. We know what battle we are in. We also have no illusions about the West: We do not idealize it; we look at the issue pragmatically. We want to live in a freer country, and at this stage, that is only possible by being part of the Western space. We want democracy, we want secure old age. We want the opportunity for development, including creative, professional, or even personal development—many talented people are simply aging at protests, and in such a mode, development is simply impossible. We used to call the previous generation the lost generation because all their talent and resources were spent fighting autocrats, and they achieved nothing except having children (except for a few fortunate exceptions). This is our situation, too. My generation is also lost, we cannot do anything because living in survival mode leaves no chance for anything.

When I say we have no illusions, I mean we also have grievances with the West, which legitimized the last several elections. For example, during the previous parliamentary elections, opposition leader Nika Melia’s office was burned down. Can you imagine that after this, any European politician would dare to say there were violations during the elections, but overall, it reflected the will of the Georgian people? Setting aside the beatings and mistreatment of people at polling stations, how could an election conducted against the backdrop of a beaten opposition reflect the people’s will?

But the thing is, we are not a banana republic. We are not our government; it does not represent us. In this small country, hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets and assert that the Georgian people can organize peaceful protests, articulate their will, and fight tirelessly for it. And in this struggle, we need our friends’ help because we are facing both an oligarchic regime and the Russian imperial plan at the same time.

The international community’s role in supporting Georgia’s democratic movement is vital for several reasons: Georgia’s geographic position makes it a crucial buffer between Russia and the Middle East, and its democratic success could inspire similar movements in the region. Supporting Georgia’s democratic movement sends a clear message that the international community stands with nations fighting for democratic values. A democratic Georgia contributes to regional stability and serves as a model for peaceful political transformation in the post-Soviet space.

Also, the international community should remember one thing: Ivanishvili is the richest man in Georgia. His wealth was estimated at $7.6 billion in 2024, a figure that in total is equivalent to nearly a quarter of Georgia’s GDP. He controls every cent in Georgia and every person in government. The poverty of the population and Ivanishvili’s immense wealth enable him to easily bribe the most economically vulnerable groups. A clear example of this was the recent elections. TV Pirveli conducted an investigative report revealing that in one village, the personal IDs of every single resident were collected in exchange for 100 GEL. These IDs were then used during the elections to cast votes on their behalf. Of course, wealth itself is not inherently a problem—on the contrary. But when wealth becomes a strategy for buying the population, it becomes a significant issue.

And most importantly, Ivanishvili’s government is supported by Putin. Therefore, the Georgian people have to fight on two fronts—against Russian disinformation and Georgian oligarchy. We know we are in an unequal fight. And we want others to know this too. If the West continues to take a silent position, we will be swallowed up by the Georgian oligarchy, which has risen from the Russian empire.

Are we afraid of the position we could find ourselves trapped in? Yes, very much. But will we fight anyway? Yes, very much!

Paata Shamugia is an award-winning Georgian poet and the former president of PEN Georgia. His poetry is translated into English, Russian, French, Turkish and German.