Taming Culture in Georgia

Key Findings:

The Georgian government has demonstrated a concerning pattern of targeting individuals in the cultural sphere who expressed views at odds with the government’s line, including artists, writers, and other cultural experts.

The Ministry of Culture has used staffing, budgetary, and organizational changes to wield control across a wide range of cultural sectors: literature, visual art, museums, cinema, and theater.

Threats to independent culture in Georgia are both the precursor to and result of broader attacks on human rights and free expression in the country.

Read “Protecting the Real Georgian Dream,” an introduction by PEN America President Ayad Akhtar >>

წაიკითხეთ ეს მოხსენება ქართულად >>

Download this report in English >>

PEN America Experts:

Program Director, Advocacy and Eurasia

Introduction

For many years, Georgians and the international community had high hopes that Georgia would be the democratic and rights–respecting foothold in a region of, at worst, authoritarian countries like Russia and Belarus or, at best, countries with shaky democratic systems and persistent human rights concerns.

Sadly, these hopes have faded in recent years, particularly since Russia’s full–scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, as Georgian activists and experts warn that the country is headed towards authoritarianism. The many indications of Georgia’s slide include unfair election practices;1Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, “Fundamental freedoms respected in competitive Georgian elections, but allegations of pressure and blurring of line between party and state reduced confidence, international observers say,” press release, November 1, 2020, osce.org/odihr/elections/georgia/469017; “Thousands rally in Georgia’s Tbilisi against election results,” Al Jazeera, November 14, 2020, aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/14/thousands-rally-in-tbilisi-to-protest-election-results violent dispersals of protestors;2Jake Cordell, “Georgian police use water, tear gas in move to break up second day of protests,” Reuters, March 8, 2023, reuters.com/world/europe/georgian-protesters-rally-tbilisi-after-violent-clashes-with-police-2023-03-08/; “HRC Report Highlights Disproportionate Use of Police at Protests,” Civil, September 28, 2023, civil.ge/archives/561310 attacks on and interference in the work of journalists and independent media;3Saba Gujabidze, “Media Attacked, Hospitalized While Covering Violent Protests in Tbilisi,” VOA July 6, 2021, voanews.com/a/press-freedom_media-attacked-hospitalized-while-covering-violent-protests-tbilisi/6207913.html; “Journalists Confirm Conversations with Clergy in Alleged State Security Files,” Civil, September 14, 2021, civil.ge/archives/440221 obstruction of the work of anti–corruption activists;4Transparency International, “Transparency International concerned over threats to civic space and corruption in Georgia,” press release, February 14, 2023, transparency.org/en/press/transparency-international-concerned-over-threats-to-civic-space-and-corruption-in-georgia; Shota Kincha, “‘These are not reforms!’: Georgia’s proposed anti-corruption agency comes under fire,” OC Media, November 1, 2022, oc-media.org/these-are-not-reforms-georgias-proposed-anti-corruption-agency-comes-under-fire/ and a widening divide between Georgian society and its political leaders.5“Letter of Concern,” Open Government Partnership, October 13, 2023, opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Georgia_Letter-of-Concern_20230413.pdf; Givi Silagadze and The Caucasus Datablog, “Datablog | Most Georgians believe that Georgia is not a democracy,” OC Media, September 20, 2022, oc-media.org/features/datablog-most-georgians-believe-that-georgia-is-not-a-democracy/ A 2022 public opinion survey showed that over 40 percent of Georgians believe their democracy is regressing.6Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia, International Republican Institute, March 2022, iri.org/resources/public-opinion-survey-residents-of-georgia/

Georgia applied for European Union (EU) membership in March 2022, just days after Russia’s full–scale invasion of Ukraine. In doing so, it ostensibly committed itself to the EU’s values of respect for democracy, the rule of law and human rights.7European Commission, “Commission Opinion on Georgia’s Application for Membership of the European Union,” June 17, 2022, neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/opinion-georgias-application-membership-european-union_en The majority of Georgians support EU membership, but the Georgian Dream political party, in power since 2012, seems increasingly to be under Russian influence.8Dato Parulava, “Georgians fear their government is sabotaging EU hopes,” Politico, July 11, 2022, politico.eu/article/georgian-fear-government-sabotaging-eu-hope/ It has been accused of taking pages directly out of Russia’s playbook: earlier this year, thousands of protestors took to the streets when the government attempted to pass a law on “transparency of foreign influence,” nearly identical to Russia’s notorious “foreign agents’ law,” which has been used to decimate Russia’s independent civil society and media.9Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Russian Federation Mariana Katzarova,” accessed October 13, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/sessions-regular/session54/advance-versions/A_HRC_54_54_AdvanceEditedVersion.docx; Kaela Malig, “How Russia’s Press Freedom has Deteriorated Over the Decades Since Putin Came to Power,” PBS FRONTLINE, September 26, 2023, pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/russia-putin-press-freedom-independent-news/; Nino Ugrekhelidze and Salome Chagelishvili, “Georgia’s new foreign agent law puts the country on the verge of a human rights crisis,” openDemocracy, March 8, 2023, opendemocracy.net/en/odr/georgia-foreign-agent-law-protest-crisis/ Opponents of these attacks on democratic values charge that former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, a billionaire who amassed his fortune in Russia and went on to found the Georgian Dream party, is still directing government policy even though he does not currently hold any public office.10“Is Georgia a Captured State?” Transparency International Georgia, December 11, 2020, transparency.ge/en/blog/georgia-captured-state; Maya Metskhvarishvili and Nino Ramishvili, “Unexplained Wealth of Top Georgian Judge Highlights Obstacles Along Country’s Path to Europe,” Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, August 7, 2022, occrp.org/en/investigations/unexplained-wealth-of-top-georgian-judge-highlights-obstacles-along-countrys-path-to-europe

International actors have also criticized Georgia’s trajectory, specifically highlighting incursions on media freedoms and the chilling effect of harassment and intimidation on freedom of expression.11For example, in the European Commission’s opinion on Georgia’s application for EU membership, it raised specific concerns about media freedoms, including intimidation and unfounded investigations which have a “chilling effect on critical media reporting.” European Commission, “Commission Opinion on Georgia’s Application for Membership of the European Union,” June 17, 2022, neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/Georgia%20opinion%20and%20Annex.pdf.

Where Georgia is heading is certainly not to the EU.

A prominent member of Georgia’s civil society, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The Georgian government continues to pursue EU membership. In June 2022, the EU conditioned Georgia’s candidacy on the country addressing 12 priorities.12Delegation of the European Union to Georgia, “The Twelve Priorities,” September 20, 2022 https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/georgia/twelve-priorities_en; and “Why was Georgia not granted EU candidate status?,” EuroNews, June 24, 2022, uronews.com/my-europe/2022/06/24/why-was-georgia-not-granted-eu-candidate-status By the European Commission’s standards, the Georgian government has made some progress in implementing the EU–imposed conditions, but the European Commission notes limited or no progress on two key priorities—de–oligarchization and media freedom.13“EC Briefs on Progress Toward EU Membership by Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine,” Civil, June 21, 2023, civil.ge/archives/549146. Experts on Georgian politics say there is a lack of political will to fully implement the EU’s demands, most of which are connected to human rights.14Interviews with Levan Tsutskiridze, Executive Director, Eastern European Centre for Multiparty Democracy, March 2023 and other prominent members of Georgian civil society who asked to be anonymous. “Where Georgia is heading is certainly not to the EU,” said a prominent member of Georgia’s civil society who spoke to PEN America on condition of anonymity.15PEN America interview, August 23, 2022.

While government interference in and increased control over state institutions regularly raises concerns, threats to the Georgian cultural sector, an essential component of Georgian civil society, and the rights to free expression, access to information, and participation in cultural life have received comparatively little attention. Over the last two years, government intimidation, harassment, and interference in the work of critical voices in the cultural sphere have increased significantly, suggesting that the government feels threatened by a vibrant and independent cultural sector.

After regaining its independence following the end of the Soviet Union, Georgia experienced a decades–long flowering of culture, which has garnered respect and praise in Georgia and abroad.16PEN America interviews with Natasha Lomouri, Executive Director, Georgia Writers’ House, August 1, 2022 and October 2, 2023 and Salomé Jashi, film director, August 3, 2022. Things began to change in March 2021 when Tea Tsulukiani, a senior member of the Georgian Dream party and a deputy prime minister who previously served as justice minister, was named minister of culture, sport, and youth affairs.17“Tea Tsulukiani Appointed Culture Minister,” Civil, March 19, 2021 civil.ge/archives/407312 Georgian cultural figures and human rights activists point to Tsulukiani’s appointment as a turning point for Georgian culture, as the ministry began to actively undermine the independence of the country’s main national cultural institutions.

This report highlights a concerning pattern of targeting individuals in the cultural sphere who have criticized the government or expressed views at odds with the government’s line. This includes artists, writers, filmmakers, museum professionals, researchers and other cultural experts.

One particularly striking pattern has been the Ministry of Culture’s interference in the system of selecting and appointing leaders of the country’s major cultural institutions, including by placing individuals without relevant expertise in decision–making roles and undermining previously transparent processes. One significant impact of this new process has been to limit and undermine the influence and work of independent, qualified professionals in the cultural sphere. Decision–making and control are now in the hands of a few ministry appointees, who seek to exclude people who are not in line with the current government’s views. In many instances, the ministry has effectively deprived these formerly independent institutions of any power to make decisions about staffing, budgets and related issues.

The incidents described in this report should also be understood in terms of the broad chilling effect they have had in the short period since Tsulukiani was appointed minister of culture. They signal to others the risks of speaking out and pressure them into silence and loyalty as the price of continuing and expanding their invaluable cultural work. Together, the incidents reflect a growing effort by the current government to control cultural life and free expression in Georgia.

Cultural rights allow people to develop and express their humanity and find meaning in their existence through their “beliefs, convictions, languages, knowledge and the arts, institutions and ways of life.”18UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, “Universality, cultural diversity and cultural rights,” A/73/227, par. 13, July 25, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/a73227-universality-cultural-diversity-and-cultural-rights-report. In the words of Karima Bennoune, former United Nations special rapporteur on cultural rights, these rights are “an expression of and a prerequisite for human dignity.”19Ibid.

Only in an environment where free expression is respected, can people enjoy full participation in cultural life and the production of culture, regardless of political affiliation or allegiance. When governments systematically assert their authority over the cultural sphere—particularly to sway the activities of writers, artists, and other cultural workers—they lay the groundwork for a political system that denies the full expression and enjoyment of all peoples’ shared humanity and dignity.

Cultural rights are “an expression of and a prerequisite for human dignity.”

Karima Bennoune, former United Nations special rapporteur on cultural rights

Cultural repression is a tactic of the authoritarian playbook globally, as is co-opting prominent cultural figures and institutions to reinforce government agendas. Cultural actors hold particular influence within societies, and can play an important role in fostering open and democratic culture. It is therefore essential not to overlook how governments are actively targeting and suppressing the independent thought that allows communities to imagine different futures. When only those who reinforce the governmental line are represented in cultural spaces, it signals to people with dissenting views that their self expression is not welcome and creates a culture of self-censorship and isolation.

იხილეთ ეს ქრონოლოგია ქართულ ენაზე >>

This report examines the Georgian Ministry of Culture’s significant infringements on cultural rights and free expression with examples from various sectors, including literature, art, film, theater and cultural research. It explores two cases that illustrate how the Ministry of Culture has attacked and undermined independent literature and art, including by targeting individuals they perceive to be critical of the government. It documents a series of incidents that demonstrate how the ministry has used staffing, budgetary, and organizational issues as part of a concerted effort to rein in independent cultural institutions in Georgia. The authors conclude with a series of recommendations to the Georgian government and the international community.

The Georgian government could yield independence back to cultural institutions should it heed the concerns raised in this report. The ongoing efforts of Georgian cultural workers seeking redress, the existence of political voices in opposition to the ruling party, and public condemnation of government interference demonstrate that course correction by the Georgian government is still possible.

Literature

The state–run Writers’ House of Georgia has been a prominent cultural institution for writers and intellectuals in Georgia for most of the 20th century and until these days. Initially it operated as a Soviet–style union where only writers who were members of the Writers’ Union and aligned with the government could share their work. It opened its doors to the public in 2013, still receiving state funding but now open to any writer.20Maya Jaggi, “Resurrecting the Poets of Tbilisi,” New York Review of Books, November 24, 2022, nybooks.com/articles/2022/11/24/resurrecting-the-poets-of-tbilisi-maya-jaggi/; Nadia Beard, “Repression regains a foothold at the Writer’s House in Tbilisi,” Financial Times, September 20, 2023, ft.com/content/3c9162de-9a22-40de-982e-4a1ac52ce34e; Tara Isabella Burton, “‘We Are in Soviet Times Again’,” City Journal, Winter 2020, www.city-journal.org/article/we-are-in-soviet-times-again It runs the annual Litera contest, one of Georgia’s most consequential literary awards, established in 2015.21Tata Shoshiashvili, “Georgia literary competition cancelled after intervention from culture minister,” OC Media, August 3, 2021, oc-media.org/georgia-literary-competition-cancelled-after-intervention-from-culture-minister/

In June 2021, the Ministry of Culture revised its policies to require that a representative of the ministry participate on the jury of any government–supported competition, and that the ministry approve the composition of the jury.22“The competition commission created by a legal entity of public law operating in the sphere of governance of the Ministry is determined by five members, one of whom is a representative of the ministry. The composition of the competition commission needs to be agreed with the ministry.” Conditions and funding rules for the activities/projects to be implemented in the field of culture by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Youth of Georgia, an annex to the law: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Youth of Georgia, The conditions of promotion of the measures/projects to be implemented in the field and about the financing method, June 3, 2021, as posted on the Ministry of Culture’s Facebook account: www.facebook.com/MinistryofCultureSportandYouth/posts/pfbid0XAiSx9PoKbUAMAHmHxGi29doebjpexhSDYd5qZ8xbJxC7LbbpW8bt9vfu3uneL8rl; And “Literary Competition ‘Litera’ Will Not be Held this Year,” Radio Liberty Georgian Service, August 2, 2021, radiotavisupleba.ge/a/31389554.html

PEN Georgia, a literary organization of more than 70 Georgian writers and a member of the global PEN International network, described this change as echoing Soviet–era “appointments of representatives of the Soviet state to contest juries, mandated to reject submissions incompatible with party ethos.”23“Culture ministry unveils new literary competition following 2021 Litera Prize cancellation,” Agenda.ge, November 22, 2021, agenda.ge/en/news/2021/3688

Writers and jury members participating in the Litera contest were deeply concerned when they learned that the government representative would be a pro–government commentator, Ioseb Chumburidze. Out of 110 books submitted for consideration, 93 were withdrawn by their authors in protest. Four of the five judges–that is, every judge beside Chumburidze–declined to participate.24“Literary Contest Canceled Amit Boycott Over ‘Censorship’ Fears,” Civil, August 3, 2021, civil.ge/archives/435257 The ministry retaliated by refusing to provide the funding for the award.25“They created Writers’ House with excitement and they don’t let members of Writers Union inside,” NetGazeti, December 3, 2021, netgazeti.ge/news/579908/

As a result, Writers’ House did not host the Litera Awards in 2021, and PEN Georgia instead hosted an alternative Litera in February 2022, supported by a crowdfunding campaign and assistance from local and international civil society donors.26Interview with former president of PEN Georgia Paata Shamugia, July 2022, and e–correspondence with Kety Abashidze, Senior Human Rights Officer of the Human Rights House Foundation, June 2023. Former PEN Georgia President Paata Shamugia explained that they received over 72,000 lari (approx. $28,000), saying, “We received payments as small as one lari [$0.38]. Everyone, even those who could not pay much, wanted to be a part of it.”27Interview with Paata Shamugia, July 2022. Winners of the alternative Litera included Rostom Chkheidze, one of Georgia’s most noted literary experts; Nana Abuladze, a 2022 resident at the prestigious University of Iowa’s International Writing Program;28Bio for Nana Abuladze, International Writing Program, University of Iowa, 2022, iwp.uiowa.edu/writers/nana-abuladze and Shota Iatashvili, whose poetry has been translated into twelve languages.29Bio for Shota Iotashvili, Literature Across Frontiers, lit-across-frontiers.org/profiles/shota-iatashvili/; List of the 2021 Alternative Litera winners (in Georgian): http://arilimag.ge/%E1%83%97%E1%83%90%E1%83%95%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%E1%83%A3%E1%83%A4%E1%83%90%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98-%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%E1%83%A2%E1%83%94%E1%83%A0%E1%83%90-2021-%E1%83%92%E1%83%90%E1%83%9B%E1%83%90/

While delighted that PEN Georgia had been able to offer an independent alternative to the Litera, at least for 2022, Shamugia said he doubted they would be able to host it again because crowdfunding is difficult to sustain.30Interview with Paata Shamugia, July 2022.

In November 2021, the Ministry of Culture launched the Best of the Year literary award. The ministry did not announce who the judges for this award would be, a major omission given that the prestige and value of the award is predicated on the credibility of the judges. “No one, even those in the literary community, knows who the jurors for this government award were,” said Shamugia.31Ibid.

In August 2023, the ministry chose to prematurely end its contract with the director of the Writers’ House, Natasha Lomouri, three months before her contract was officially due to expire.32“Georgian Dream Faction Member Appointed Head of Writers’ House amid Writers’ Protests,” Civil, August 11, 2023, civil.ge/archives/555501 Lomouri had served as director of the Writers’ House since 2011.

Lomouri told PEN America that she was given only five days’ notice, by phone on August 2, that her contract had been prematurely terminated.33Interview with Natasha Lomouri, October 2, 2023. The Ministry of Culture then announced on its Facebook page that it had appointed Ketevan Dumbadze as its new director.34Ministry of Culture, Sports and Youth of Georgia, “Ketevan Dumbadze will head the Writers’ House of Georgia,” Facebook, August 10, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=603097975339562&set=a.230957332553630 Dumbadze is a member of parliament for the Georgian Dream party; she has offered support for her party’s efforts to target “foreign influence” over funding for Georgian civil society initiatives.35“Law on ‘Transparency of Foreign Funding’ Passes 76–13 in the First Reading,” Civil, March 7, 2023, civil.ge/archives/529567 Following Dumbadze’s appointment, the Writers’ House issued a statement protesting the appointment, which had not been supported by its members, emphasizing that “the direct appointment of a new director in the organization jeopardizes the free and uncensored management” of Writers’ House projects.36Statement from the Writers’ House’s Facebook page on August 12, 2023. Previously, such appointments were approved by the Board of Writers’ House.37Interview with Natasha Lomouri, October 2, 2023.

Among the projects it feared would be censored or cut, the Writers’ House listed the Litera Prize, alongside its newly–opened Museum of Repressed Writers, an initiative intended to educate younger Georgians about the Soviet suppression of the country’s writers and other cultural figures.38Interview with Natasha Lomouri, August 1, 2022.

Visual Art

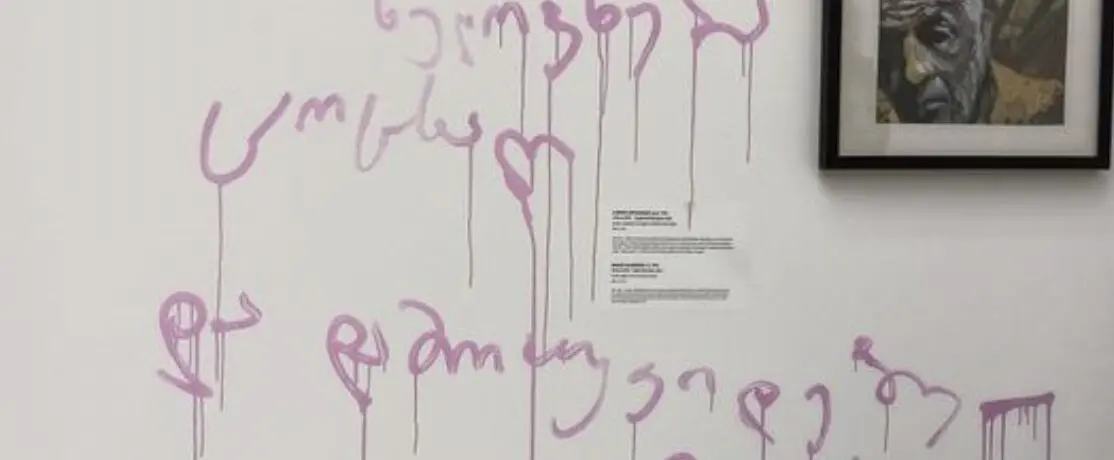

On February 4, 2023, at the opening night of an exhibition at Georgia’s National Gallery, artist Sandro Sulaberidze removed his own self–portrait from the gallery wall and painted in its place the phrase “Art is alive and independent!” The Ministry of Internal Affairs quickly launched a criminal investigation against him, alleging “theft that caused significant damage.”39Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA), “GYLA’S Statement Regarding the Case against Sandro Sulaberidze and the Protest of February 12, 2023,” February 13, 2023 gyla.ge/en/post/saias-ganckhadeba-sandro-sulaberidzis-tsinaaghmdeg-aghdzrul-saqmesa-da-2023-tslis-12-tebervlis-protesttan-dakavshirebit#sthash.TMLWq1xB.dpbs. Other artists participating in the exhibition signed a statement in support of Sulaberidze, criticizing the government’s “antagonism and repression”; his supporters also organized a demonstration on February 12 in front of the gallery.40“Statement of Some of the Participants of the Exhibition ‘Self Portrait with a Mirror,’ February 11, 2023, at.ge/2023/02/11/avtoportreti/?fbclid=IwAR0atnfGfnb-7ipVHU_n-tvsiuHEXeS0QXFdGg1QU1p58IXoqPrPzoEQRaw; “A Protest Action is Taking Place Near the National Gallery,” RFE/RL, February 12, 2023. PEN Georgia issued a statement condemning the criminal investigation of Sulaberidze.41“Statement of the PEN Center of Georgia,” February 11, 2023, pencenter.ge/index.php?do=full&id=1993%2F&fs=e&s=cl&fbclid=IwAR0QGwQgVBfpw-e9DM6WGmWRjl7hx0XkidBdjSOf18XvmipXdlAnDp4DMRs

Later that day, President Salome Zourabichvili publicly questioned the intensity of the police response to the protest (20 police cars had been mobilized in response) and wondered aloud whether “the artist represented such a threat to the state.” Zourabichvili said the ministry’s aggressive response reminded her “of another era,” a comment widely understood to be a reference to Soviet repression of independent artists.42“The Start of the Investigation against Sandro Sulaberidze was Followed by a Protest,” Civil, February 13, 2023, civil.ge/ka/archives/525254. The following day, February 13, the Ministry of Culture’s inspection service entered her presidential residence and removed five paintings, saying that their lease from the art museum had expired. The presidential administration criticized the move as politically motivated.”43“Presidential Administration Calls Ministry of Culture Inspection a ‘Political Attack,’” Civil, February 13, 2023, civil.ge/archives/525396. Zourabichvili—who is not a member of the Georgian Dream Party—has publicly criticized the ruling party for growing closer to Russia and stoking fears of war.44“Georgian President Criticizes Government In Independence Day Speech,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Georgian Service, May 26, 2023, rferl.org/a/georgia-president-criticizes-government-democracy-reforms/32429525.html.

The Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association (GYLA), a leading independent human rights advocacy group, conducted their own investigation into Sulaberidze’s actions and found that there was no evidence of theft.45Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA), “GYLA’S Statement Regarding the Case against Sandro Sulaberidze and the Protest of February 12, 2023,” February 13, 2023, gyla.ge/en/post/saias-ganckhadeba-sandro-sulaberidzis-tsinaaghmdeg-aghdzrul-saqmesa-da-2023-tslis-12-tebervlis-protesttan-dakavshirebit#sthash.TMLWq1xB.dpbs. Theft is defined as “the covert possession of someone else’s movable property for the purpose of its unlawful appropriation,” in Georgian law The GYLA argued that the criminal investigation “significantly damages the guarantees of the freedom of expression,” and that the investigation appeared designed to put pressure on artists and warn “other persons to refrain from expressing their positions on certain issues.”46Ibid. The authorities closed the investigation into Sulaberidze’s actions on February 14 without bringing any charges against him.47“Investigation against Artist Sandro Sulaberidze Dropped by Ministry of Interior,” Civil, February 15, 2023, civil.ge/archives/525792.

Zourabichvili said the ministry’s aggressive response reminded her “of another era,” a comment widely understood to be a reference to Soviet repression of independent artists.

Museums

In 2021 the Ministry of Culture issued a series of orders calling for the reorganization of the entities under its jurisdiction, including the National Museum of Georgia and the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Protection. These orders included the creation, in April 2021, of a new five–person Directorate of the National Museum of Georgia empowered to make decisions on all matters, including those related to research and scientific processes, for the 14 museums in its network. This action centralized decision–making and siphoned authority away from individual museum and institute managers.48Interview with Eka Kiknadze, former manager Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts August 5, 2022, and “Fight at the Museum: The Georgian Government Takes on the Arts,” Nadia Beard, RFE/RL, September 9, 2022. The directorate currently consists of officials drawn mostly from the Ministry of Justice, penitentiary system, and sports institutions, many of whom appear to lack qualifications and experience in the management and oversight of museums and cultural institutions.49Email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, chair, Union of Science, Education and Culture Workers of Georgia, July 2023 who identified five public officials by names.

In 2021, the ministry of culture also appointed new leadership for the main cultural agencies and initiated reorganizations that resulted in the dismissal of at least 75 employees from the Georgian National Museum and at least 80 from the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Protection, according to the Union of Science, Education and Culture Workers of Georgia (USECW), which represents the majority of the fired workers. Museum workers created the union in May 2022 in the midst of the aggressive reorganizations and interference with grant funding for their projects.50Email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, chair, Union of Science, Education and Culture Workers of Georgia, March and April 2023; interview with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022; and “Fight at the Museum: The Georgian Government Takes on the Arts,” Nadia Beard, RFE/RL, September 9, 2022.

The reorganization process began with the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts where, for example, Eka Kiknadze, the manager responsible for personnel and the museum’s rehabilitation plans, was first demoted to laboratory assistant in mid–2021, then fired in January 2022 after a new group of museums was created.51Interview with Tsira Jananashvili, attorney and member of Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, May 11, 2023, and “Museum, Cultural Ministry in Fresh Grants Controversy,” Civil, February 12, 2022, civil.ge/archives/472408. Other museums were also affected by the reorganization and mass layoffs. For example, in May 2022 at least 40 workers were also reportedly fired from the Simon Janashia Museum, one of the country’s main history museums.52Email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, March and April 2023.

The firing of museum workers has appeared to follow a consistent pattern.53Interviews with Salome Shubladze, lawyer from Social Justice Center, April 3, 2023, and with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy, April 12, 2023. A commission of individuals selected by the Ministry of Culture, including former Ministry of Justice employees with no direct previous experience in the arts, briefly interviewed each employee, ostensibly to assess their qualifications for their position.54Interviews with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022, and with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023. However, according to dismissed employees and their lawyers, they were not questioned about their skills or professional experience. Instead, they were asked about their support for the Ministry of Culture’s plans, their connections to opposition politicians or former government officials, and whether they had publicly criticized the ministry or government on social media, including whether they were associated with a petition opposing the Ministry’s plans for one of the museums.55Interviews with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022; with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023; and with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023. Statement of the Participants of the Action Supporting the Art Museum to the Parliament of Georgia and the Ministry of Culture and Monuments Protection of Georgia, available at Manifest.ge, petition.

The tone of these so–called assessments was often aggressive, the fired workers reported. One museum worker described the experience to PEN America as resembling an interrogation “in a penal colony.”56Interview with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022. Lawyers for the dismissed workers said that many of those who were interviewed felt “humiliated,” and “very insulted,” by the process whereby their professional qualifications were judged by people who they believed had little, if any, relevant expertise.57Interview with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023.

The tone of these so–called assessments was often aggressive… One museum worker described the experience as one that resembled an interrogation “in a penal colony.”

Given the nature of the interviews, workers overwhelmingly felt they were being retaliated against for their criticism of the Ministry of Culture’s actions, including—as reorganization processes began—their criticism of the reorganization itself.58Interviews with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022; with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023; and with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023; email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, March and April 2023; and “40 More Dismissed from Museum System, Labor Union Says,” Civil, May 5, 2022, civil.ge/archives/492518. Eka Kiknadze, for example, openly disagreed with the ministry’s perspective on the future of the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts. She helped create the petition expressing those concerns, solicited signatures, and sent the petition to parliament, prior to her demotion and dismissal.59Interviews with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022, and with Tsira Jananashvili, May 11, 2023.

In a September 2022 interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the USECW Chair, Nikoloz Tsikaridze, an archeologist, said, “Who knows what the real reason for me being fired really was. They didn’t give me a score after my interview, and they still won’t hand over documents explaining what their criteria for the firings were.”60“Fight at the Museum: The Georgian Government Takes on the Arts,” RFE/RL, September 9, 2022, rferl.org/a/georgia-museum-government-cultural-attack/32026232.html Lela Khatridze of the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy, an NGO that represents 31 former employees of national cultural institutions, has concluded that “The reorganization was a political tool to get rid of unwanted employees.”61Interviews with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022; with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023; and with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023. August 10, 2023

Who knows what the real reason for me being fired really was. They didn’t give me a score after my interview, and they still won’t hand over documents explaining what their criteria for the firings were.

Nikoloz Tsikaridze, Chair of Union of Science, Education and Culture Workers of Georgia (USECW)

Many of the fired workers are suing the Ministry of Culture for unfair dismissals. Some cultural workers have won their court cases and have been awarded back wages and/or compensation, although they have not been reinstated to their positions, which are now occupied by others.62Those who have won include: Guga Gogadze, Dinara Vachnadze, Zurab Berukashvili, Irma Managadze, Nana Buadze, Giorgi Jamburia, Eka Kiknadze, Lika Mamatsashvili, Natia Khuluzauri. Email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, June 2023. Most cases are still pending in the court of first instance or on appeal.63Interviews with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023; with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023; and with Tsira Jananashvili, May 11, 2023. In May 2023, the Tbilisi City Court found Eka Kiknadze’s demotion illegal and ordered the Ministry of Culture to pay her 5,000 GEL ($1,920) in compensation.64“Tbilisi City Court Partially Satisfies Claim of National Museum Employee,” Civil, May 30, 2023, civil.ge/archives/545378.

Many of those fired from Georgia’s leading cultural institutions were senior staff and department heads, including prominent and well–respected researchers, scientists, and specialists in their respective fields. Many principal investigators and key personnel were also dismissed.65Interview with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022, and email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, March and April 2023. More junior staff members were also targeted in some cases. Interviews with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022, and with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023. The consequences of the dismissals will inevitably have a lasting negative impact on cultural development, expression, and preservation in Georgia. According to a joint statement by three of the Georgian NGOs representing some of these workers, “the dismissal of qualified professionals on this scale is an inexplicable decision that will cause significant damage to the cultural sphere.”66Interviews with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023, and with Lela Khatridze and Tatia Kinkladze, April 12, 2023, and “The Social Justice Center, SAIA and ISFED will protect the interests of those dismissed as a result of Tsulukiani’s personnel purge in the field of culture,” The Social Justice Center (Georgia), January 31, 2022, socialjustice.org.ge/ka/products/tsulukianis-mier-kulturis-sferoshi-chatarebuli-sakadro-tsmendis-shedegad-gatavisuflebulta-interesebs-sotsialuri-samartlianobis-tsentri-saia-da-isfed-daitsavs. See also for example: Social Justice Center, “The employee dismissed as a result of Tsulukiani’s personnel purge won the court case,” The Social Justice Center, August 9, 2022, socialjustice.org.ge/ka/products/tsulukianis-sakadro-tsmendis-shedegad-gatavisuflebulma-tanamshromelma-sasamartlo-dava-moigo.

Many of the dismissed cultural workers have reportedly not found new employment, likely because there are few employment opportunities for people with their highly specific expertise.67Interview with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023.

Regarding her dismissal as manager of the Museum of Fine Arts, Eka Kiknadze said, “I believe that one day my rights, and the rights of all those unjustly fired by this government in the last year and a half, will be restored. But the damage caused to Georgian cultural heritage might be irreparable.”68Interview with Eka Kiknadze, August 5, 2022.

I believe that one day my rights, and the rights of all those unjustly fired by this government in the last year and a half, will be restored. But the damage caused to Georgian cultural heritage might be irreparable.

Eka Kiknadze, former manager of the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Art

Government Interference in Grants for Cultural Research

A February 2022 Ministry of Culture decree stipulated that its directorate would take control over the application process for, and implementation of, grants awarded for projects in its museums.69“Makes a decision on the application of the National Museum and museums/groups of museums included in its association of museums to the grantor (donor), request/credit of the grant amount or any issue related to the disposal of the grant.” Amendments to “About the approval of the statute of the legal entity of the National Museum of Georgia” of the Minister of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Georgia dated June 18, 2019, No. 110/N, February 1, 2022, matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/5373762?publication=0&fbclid=IwAR35C9uzOyhMVi_n-F3tO8Bf1qOm8d7_T4KGsIiH1rKVdV1HfwskBZbDeAE. As a result, the Ministry of Culture undermined museum workers’ and researchers’ opportunities to access and utilize grant funding from the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation, part of the Ministry of Education and the only major source of funding for cultural researchers that is not controlled by the Ministry of Culture.70Interview with Nino Evgenidze, Executive Director of Economic Policy Research Center, Tbilisi, March 2023. For more detail on the grant funding and dismissed cultural workers see: “Public Defender Finds Discriminatory Treatment of Former National Museum Employees,” Civil, October 27, 2022, civil.ge/archives/513084; and “Museum, Cultural Ministry in Fresh Grants Controversy,” Civil, February 12, 2022, civil.ge/archives/472408.

The directorate retroactively applied this decree by blocking 13 grants that had already been reviewed by the Georgian National Museum’s scientific council in March 2021, in accordance with the law, and awarded by the foundation. The directorate ignored this process and demanded to review the grants using its own scientific council.71Email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, March and April 2023; “Museum, Cultural Ministry in Fresh Grants Controversy,” Civil, February 12, 2022.

Under the country’s law on science, technologies, and their development, an institution’s scientific council—whose activities include grant approvals—must be composed of scientists from the institution.72Law of Georgia on Science, Technology, and their Development,” Article 10.2.1, faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/geo181479ENG.pdf. According to Nikoloz Tsikaridze from the USECW, the cultural workers union, the Ministry of Culture’s decree not only restricted academic freedom, but ignored this legislation by putting people with no scientific experience on the National Museum’s council.73Email correspondence with Nikoloz Tsikaridze, March and April 2023 After negotiations with the directorate’s scientific council, Tsikaridze recounts, researchers were able to secure the reinstatement of 12 of the 13 grants; the only grant that was not reinstated had been awarded to three prominent employees of the Fine Arts Museum, who had been fired.74Ibid.

Yet even for those whose grants were allowed to proceed, the USECW indicated that the ministry continued to prevent the research from going forward by denying dismissed employees access to museum collections, use of the facilities, and funds for fieldwork within the scope of the grants, in violation of an agreement reached between the Georgian National Museum directorate, the USECW, and key project personnel. As of this writing, per the USECW’s information, most of the research and archeological field projects are still either frozen or delayed. The directorate has either not responded at all to researchers’ letters or has taken a long time to reply. The union has faced similar stonewalling.75Ibid.

With the directorate still in place, subsequent projects may well face the same impositions and efforts at government control.

Tsikaridze expressed his dismay, saying, “We are deeply concerned about the situation developing in our field; our research projects, international scientific network and functional system in the field of culture and related sciences are on the verge of collapse…We are struggling and trying to save what is left.”76Ibid.

Salome Shubladze of the Social Justice Center, another NGO that represents nine dismissed cultural workers, reached a similar dire conclusion: “The effect [of the grant manipulation] was the complete removal of cultural workers from their work,” she said.77Interview with Salome Shubladze, April 3, 2023.

The directorate’s control over cultural grants may also be exercised to restrict grantmaking by foreign embassies in Georgia interested in supporting cultural projects, warned Nino Evgenidze, Executive Director of Economic Policy Research Center in Tbilisi.78Interview with Nino Evgenidze, March 2023.

Cinema

In mid–March 2022, the Ministry of Culture fired Gaga Chkheidze, director of the Georgian National Film Center (GNFC), a state agency tasked with promoting and funding national filmmaking. The dismissal was widely considered to be a politically motivated action targeting an important national cultural institution. The formal justification for Chkheidze dismissal was alleged irregularities in an audit of the film center.79Interview with Gaga Chkheidze, August 5, 2022.

Chkheidze disputes the findings of the audit, which was ordered in March 2021 and completed in March 2022. According to Chkheidze’s lawyer, the Ministry of Culture sent the audit report to the prosecutor’s office, which declined to take any action against him.80Email correspondence with Lela Khatridze, International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy, July 2023. Chkheidze believes that his removal is linked to Facebook posts he wrote in March 2022 in which he criticized the government. In one post, he questioned why the Georgian government had not condemned Russia’s destruction of cultural heritage in its war on Ukraine. In another, he called on the Ministry of Culture to suspend its contract to purchase films from Russia’s state film archive in response to Russia’s full–scale invasion of Ukraine.81Interview with former director of the Georgian National Film Center Gaga Chkheidze, August 5, 2022; and Vladan Petkovic, “Former Georgian film center director speaks out after dismissal (exclusive),” ScreenDaily (UK), April 6, 2022, screendaily.com/news/former-georgian-film-centre-director-speaks-out-after-dismissal-exclusive/5169384.article; and “’Punitive Operation’: Culture Ministry Sacks Head of National Film Center,” Civil, March 17, 2022, civil.ge/archives/479669.

Chkheidze also said that following Minister Tsulukiani’s appointment, there had been many months of interference by the Ministry of Culture in the film center’s work and in his role as director. For example, the ministry began requiring Chkheidze to get ministerial approval for his television appearances, and then blocked some of them. He also alleges that the ministry pressured him to award a prize to their preferred film, rather than allow an independent jury to select the winner.82Interview with Gaga Chkheidze, August 5, 2022, and “Gaga Chkheidze: If The Minister of Culture Does Not Cancel the Order of My Release, I Will Appeal,” Radio Liberty Georgian Service, March 17, 2022, radiotavisupleba.ge/a/31758209.html.

On June 5, 2023, film center employees published an open letter on the center’s website demanding that the center be allowed to operate independently. The letter was subsequently removed. Some employees then issued critical statements on social media. Less than a week later, on June 11, the ministry announced a full reorganization of the GNFC and appointed as new acting director Koba Khubunaia, the former deputy head of the National Agency for Crime Prevention, Non–Custodial Sentences, and Probation under Tsulukiani at the Ministry of Justice. He dismissed the GNFC deputy directors and appointed Bacho Odisharia, a news anchor at the anti–Western television channel PosTV as deputy head of the film production department. Odisharia was quoted as saying, “I will find out who has what problems, who is worried about what, I will try to fix it. I will also find out why this is the subject of protest.”83“Bacho Odisharia confirms that he has been appointed as deputy head of the department at the film center,” NetGazeti, June 13, 2023, netgazeti.ge/news/674628/; and “Is Culture Minister Taking Over the Film Center?” Civil, June 15, 2023, civil.ge/archives/548248.

There has been vocal condemnation of these actions against the GNFC from the center’s employees and civil society. In mid–June, film center employees issued another public letter demanding a halt to the reorganization, pending the selection of the new director through a fair, transparent, and competitive process by a panel of film industry professionals. Representatives of the Georgian filmmaking industry also signed the letter.84“Culture Minister is Dismembering the Film Center,” Civil.ge, June 15, 2023, https://civil.ge/archives/548248; list of more than 400 signatories https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSc8QZ18l5YkLGE-zC88DJLxJaSojFw5iu6CkkT0pn8gSUhq8Q/viewform. Sixty writers immediately issued a solidarity letter in support of an independent GNFC;85“A letter from writers, translators and publishers: We support film professionals”, JAM News, June 16, 2023, https://jam-news.net/ge/kinos-mkhardamcheri-werili/. numerous independent Georgian and international human rights organizations also signed a letter condemning threats to freedom of expression in Georgia.86“NGOs: Limiting the freedom of expression of the cultural and artistic sector is unacceptable”, Formula News, June 21, 2023, https://formulanews.ge/News/92831.

Canceling Taming the Garden, a Documentary Film

Following the dismissal of Chkheidze, the new president of the Georgian Film Academy canceled a series of six screenings of the award–winning documentary film Taming the Garden, by celebrated Georgian director Salomé Jashi, scheduled for spring 2022.87“Salomé Jashi: Awards,” IMDB, imdb.com/name/nm4480391/awards/?ref_=nm_awd.; “Taming the Garden: You Haven’t Seen It All,” Nini Gabritchidze, Civil, May 24, 2022, civil.ge/archives/491900 The film had its world premiere at the Sundance Film festival in 2021 and was screened at festivals around the world.88“Taming the Garden: News,” tamingthegarden-film.com/en/news/. It depicts a powerful man who commissions workers to uproot trees that are centuries old and plant them in his private garden. The viewer is informed that the name of the man is Ivanishvili, though this is not emphasized in the film.89“Taming the Garden, A Film by Salomé Jashi,” tamingthegarden-film.com/en/.

Bidzina Ivanishvili, a former prime minister of Georgia, allegedly ordered more than 200 trees be moved, beginning in 2016, from various locations in Georgia to a privately owned garden opened to the public near the southern city of Batumi on the Black Sea Coast, despite environmental concerns and disruption to public life in areas where the trees were uprooted and transported.90Giorgi Lomsadze, “Georgia’s park of runaway trees,” EurasiaNet, August 19, 2020, eurasianet.org/georgias-park-of-runaway-trees.

In a media interview, Jashi recounted learning about the cancellation of the screening. “[The new president of the film academy] told me the film ‘creates political divisions in the public.’ It’s an outrageous argument, because it’s normal for any film or work of art or culture to cause a diversity of opinion.”91“Fight at the Museum: The Georgian Government Takes on the Arts,” Nadia Beard, RFE/RL, September 9, 2022.

In an interview with PEN America, Jashi said, “I’m asking myself why the Ministry of Culture has this campaign against culture? Well, because arts and culture are among those mediums that define the way people think. Art and films from Georgia are becoming more and more known internationally. A lot of Georgian artists now represent the country, and often critically. The government doesn’t like it.”92Interview with filmmaker Salomé Jashi, August 3, 2022.

In June 2023, Georgian Dream Party Chairman Irakli Kobakhidze criticized Jashi and Taming the Garden, claiming the film was politically motivated and should not have been made. “The main thing is that a film with shameful content should not be financed, it should have the right content,” he said.93“’Sakdok Film’ Considers Kobakhidze’s Statement as a Step Towards Cinema Censorship,” Radio Liberty Georgian Service, June 20, 2023, www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/32466341.html. The film’s producers responded that the statement was a personal attack on Jashi, directed against free expression and in favor of state censorship of cinema.”94Ibid.

Theater

Lasha Chkhvimiani was the director of the State Drama Theater in Dmanisi, a small mining town about 100 km southwest of Tbilisi, from 2017–21. In early 2022, Chkhvimiani applied to serve another four–year term. However, in February 2022, without explanation, the Ministry of Culture canceled the selection process, and appointed another candidate who had reportedly not applied for the position.95“The Former Artistic Director of the Dmanisi Drama Theatre Complains to the Ombudsman against Tsulukiani for Discrimination,” April 5, 2022, News On.ge, on.ge/story/101753-დმანისის-დრამატული-თეატრის-ყოფილი-სამხატვრო-ხელმძღვანელი-წულუკიანს-დისკრიმინაციის-გამო-ომბუდსმენთან-უჩივის

Chkhvimiani links his removal to his 2019 production of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, which is about political corruption.96Interview with theater director Lasha Chkhvimiani, August 23, 2022. Chkhvimiani received significant criticism for staging the play, including from the city’s mayor. After the premiere, the mayor left a message for Chkhvimiani at his home saying, “I should not see this idiotic and grotesque play on the stage again!” The mayor summoned Chkhvimiani to his office the following day and warned him that the theater building belonged to the state.97Ibid. The municipality later terminated its financial subsidy of the theater.98“The Former Artistic Director of the Dmanisi Drama Theatre Complains to the Ombudsman against Tsulukiani for Discrimination,” April 5, 2022, News On.

I should not see this idiotic and grotesque play on the stage again!

The mayor of Dmanisi speaking to director Lasha Chkhvimiani following his staging of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People.

Shortly after the play was staged, RMG, a mining company with a history of close links to the government and the main employer in Dmanisi, ended an employment contract it had with Chkhvimiani’s father, telling him that his family’s actions “damage the company.”99Interview with Lasha Chkhvimiani, August 23, 2022. Chkhvimiani also claimed that civil servants stopped attending the play, apparently out of fear of reprisals from their supervisors.100“’You have to hand over all the details to us’” Interview with the former head of the Dmanisi Theater,” Tornike Mandaria, Radio Liberty Georgian Service, February 14, 2022, www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/31703213.html.

Radio Liberty’s Georgian service reported that in Chkhvimiani’s case and the case of two other candidates for artistic director positions at dramatic theaters, the recommendation council, which consisted of theater professionals qualified to assess the candidates’ qualifications, had a perfunctory role, and the final decision was made by the Minister of Culture.101“Regarding Changes to the Law of Georgia on ‘Professional Theatres’,” July 15, 2020, Legislative Herald of Georgia, matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/4919851?publication=0. While this selection process is permitted under Georgian law, it goes against precedent: in the past, the expert recommendation councils have traditionally selected the best candidate independently, which the ministry then approved.102Interview with Lasha Chkhvimiani, August 23, 2022.

In response to complaints by Chkhvimiani and other candidates, on November 5, 2022, the Public Defender’s Office (Ombudsperson) made a series of recommendations to the Ministry of Culture. It called on the ministry to ensure to the greatest extent “the involvement and transparency of qualified experts in the field and the interested public in the process of making decisions related to professional state theaters,” and to limit the ministry’s direct involvement in selection of directors, except in certain circumstances.103“The Ombudsman Considered the Appointment of Managers in Theatres,” Radio Liberty Georgian Service, November 5, 2022, radiotavisupleba.ge/a/32116943.html.

National and International Human Rights Law

Georgia’s constitution protects freedom of expression, stipulating that “No one shall be persecuted because of their opinion or for expressing their opinion.”104Constitution of Georgia, August 24, 1995, as amended, art. 17, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/30346?publication=36. The Georgian Labor Code prohibits discrimination, including harassment and dismissal due to political or other opinions.105Labor Code of Georgia, December 17, 2010, with amendments, art. 2(3). https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/1155567?publication=23. Under international human rights law, the right to freedom of expression includes the opportunity to express both one’s ideas and one’s beliefs without interference and fear of retaliation. The right to free expression is not only fundamental, but also multi–faceted; it includes the right of anyone to seek and receive information and ideas of all kinds through various means, including orally, in writing, in print, and in the form of art and artistic expression.106International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), entered into force March 23, 1976, art. 19, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights, and Human Rights Committee, General Comment no. 34, September 12, 2011. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/gc34.pdf.

Diversity of political and other views shared by writers, artists, filmmakers, curators, theater directors, researchers, and others in the cultural sphere is an essential measurement of freedom of expression in any society, and it includes the right of members of the public to receive information and ideas without interference by public authorities. Interference with the work of writers, filmmakers, artists, and others infringes on their individual rights to express themselves freely, as well as the rights of all others who would like to access and enjoy literature, film, and art in all its various forms.

Under international human rights law, everyone has the right to culture, including to freely express themselves and create diverse forms of art. All people also have the right to access, contribute to and participate in cultural life, and to the enjoyment of heritage.107International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), entered into force January 3, 1976, art. 15. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cult These rights are most forcefully enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, which Georgia has ratified.108United Nations Human Rights Treaty Bodies, Ratification Status for Georgia, UN Treaty Body Database, last accessed October 5, 2023, ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=65&Lang=EN

The right to culture also includes the rights to benefit and participate in scientific progress,109ICESCR, art. 15; Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment no. 25, April 30, 2020, documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/108/12/PDF/G2010812.pdf?OpenElement. which can be understood as the theoretical and practical research and examination in all fields of inquiry, including history, art history, archeology, and other sciences.110ICESCR, art. 15; “Cultural Rights,” ESCR Net, escr-net.org/rights/cultural. Science requires the “robust protection of freedom of research”; governments must guarantee the freedom of individuals to undertake research and protect them from undue influence on their independent judgment.111Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment no. 25. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights.

The Georgian government’s removal of leading researchers from cultural institutions and denial of grants and other resources to researchers risks undermining both the rights of those individual to culture and participation in scientific progress, and the rights of Georgians and others around the world to benefit from research, information, and knowledge in a number of scientific and cultural fields. The punitive actions and systemic assaults against the artistic and professional independence of Georgia’s cultural institutions, as well as against individual artists and professionals, will also have a chilling effect on freedom of expression in the entire country and further narrow civic space.

These actions are also inconsistent with the recommendations of Farida Shaheed, the former UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights. She recommends that “state cultural policies need to take artistic freedoms into consideration, in particular when establishing criteria for selecting artists or institutions for State support, the bodies in charge of allocating grants, as well as their terms of reference and rules of procedure. The system in place can help to avoid undue government influence on the arts.”112UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, “Report on the right to freedom of artistic expression and creation,” A/HRC/23/34, March 14, 2013, ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/ahrc2334-report-right-freedom-artistic-expression-and-creation#:~:text=The%20Special%20Rapporteur%20encourages%20States,protect%20and%20fulfil%20this%20right.

Conclusion and the Way Forward

The Georgian government’s efforts to infringe on the independence of cultural actors and institutions should not be understood as just a bureaucratic whim, but rather as a concerted effort to impede freedom of expression and cultural rights. These attacks pose significant threats to the exercise of these rights in Georgia, and also undermine the enjoyment of other human rights.

The efforts to undermine independent cultural institutions, attack and silence cultural figures and suppress artistic expression that challenges and criticizes the government are especially poignant given the history of the country: Several of the people PEN America interviewed for the report referred to the country’s painful history under Soviet occupation, during which all art and culture was systematically repressed or exploited for government propaganda purposes. The democratic and rights–respecting progress of the country, they stressed, can be viewed through the prism of artistic and cultural freedom. Cultural workers and the flourishing of Georgian culture after the fall of the Soviet Union contributed to building a more tolerant and inclusive society.

The concerns expressed by civil society, cultural defenders and human rights activists in Georgia are increasingly shared by international actors. In its initial opinion on Georgia’s application for EU membership, the European Commission raised specific concerns about media freedom and other human rights issues. The United States has voiced disapproval in occasional statements and in its annual human rights reports, including its concerns over the “narrowing of the media environment.”113“Ambassador Degnan: We see the Narrowing of Media Environment in Georgia,” Civil, March 25, 2023, civil.ge/archives/533576; “Deputy Assistant Secretary For Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, Kara McDonald’s Remarks to Media at Parliament, US Embassy in Georgia, June 10, 2022, usembassy.gov/deputy-assistant-secretary-for-democracy-human-rights-and-labor-kara-mcdonalds-remarks-to-media-at-parliament/.

In its September 2022 concluding observations on Georgia, the UN Human Rights Committee mentioned the need for stronger protection of freedom of expression for artists and writers, among others, calling on the Georgian government to “redouble its efforts to prevent and prohibit public officials and private actors … from interfering with the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression of journalists, artists, writers, human rights defenders and government critics.”114“Concluding Observations on the Fifth Periodic Report of Georgia,” UN Human Rights Committee, 135th Session, September 2022, United Nations Digital Library, last accessed October 5, 2023, digitallibrary.un.org/record/3987487?ln=en.

Salomé Jashi, the filmmaker, articulated the power and importance of cultural and artistic expression and the role that cultural rights play in creating and sustaining fairer, just, and rights respecting societies. She said, “My feeling is that our minister of culture sometimes sends this message to the public that artists look for funding for their own needs. But we do it to create artworks to inspire people. We need support from other countries who support freedom of expression. We need exhibition places showing movies which speak about freedom, human rights, and democracy. This is the topic we need local public awareness about, in order to change our environment, make it better, more welcoming, more open, more free.”115Interview with Salomé Jashi, August 3, 2022.

The Georgian government, in its efforts to repress, manipulate and control the independence and vibrancy of Georgian culture, clearly recognizes that power and is afraid of it. As cultural workers increasingly find themselves on the front line of challenging the growing authoritarianism in Georgia, the world should support their struggle and help them uphold human rights.

Recommendations to the Government of Georgia

- Pause the effort to reorganize the Georgian National Museum system and the Georgian National Film Center. Establish an independent council of experts and professionals in relevant spheres to advise the Ministry of Culture, thus enabling a diversity of views and relevant expertise to shape the ministry’s plans for the nation’s museums, National Film Center, and other institutions and programming.

- Commit publicly to ensuring that people with the appropriate expertise evaluate staff hires for museums and other cultural institutions in a lawful, fair, legitimate, and transparent manner.

- Reinstate staff to their previous positions if they have been dismissed unlawfully, as determined by court proceedings, unless such reinstatement is no longer legally possible.

- Ensure effective enforcement of judicial decisions regarding dismissed cultural workers and similar cases in a timely manner, including payment of compensation.

- Enable and respect the decisions of independent expert bodies composed of qualified professionals to make decisions and recommendations in the cultural field, as in the selection of state theater directors, scientific councils reviewing grant applications, and similar bodies.

- Negotiate in good faith and respect the agreements with the Union of Science, Education and Culture Workers of Georgia (USECW).

- Ensure that recipients of research and other grants for cultural and scientific cultural purposes can pursue their projects without interference and with the support of relevant national institutions as stipulated in the project documentation and other agreements. This includes access to museum collections and relevant artifacts and other resources.

- Allow researchers to transfer their grant-funded projects to other institutions.

- Actively implement the 12 priorities the EU has established for Georgia’s candidacy, which are designed to advance human rights and democracy in the country.

Recommendations to the International Community, Including the EU and US

- Provide financial and other support for independent artists, writers, filmmakers, performing artists, and others in Georgia’s cultural community and refuse any efforts by the Georgian government to control or interfere in such support.

- Publicly and privately send clear and strong messages in support of human rights and free expression and freedom of information, and specifically mention the importance and relevance of the cultural sphere in advancing free expression.

- Support independent civil society organizations, including a diversity of cultural organizations. Exercise due diligence in identifying organizations to support and prioritize the support of independent organizations

- Insist that the Georgian government upholds the rule of law, investigates and holds accountable those responsible for violations of freedom of expression and the right to information.

- Reinforce the need for the Georgian government to adhere to human rights and free expression principles as a foundational element of its bilateral relationships with the United States and other democracies.

- Urge the Georgian government to reject laws and practices that limit free expression, including those that

- undermine the independence of cultural institutions;

- chill expression in writing, the arts, or cultural institutions due to a fear of actual or perceived retaliation based on political leaning or affiliation;

- criminalize, chill, or otherwise undermine speech and/or writing;

- restrict the space for civil society organizations to operate freely.

Methodology

This report is based on substantial desk research from publicly available sources in English and Georgian, as well as 12 interviews conducted between August 2022 and June 2023 with cultural workers in Georgia and lawyers representing them in legal disputes before Georgian courts. Interviews were also conducted with several experts on Georgian politics and human rights. On May 5, 2023, PEN America sent a letter to the Ministry of Culture with a series of questions related to the findings of this report and asked for the ministry to provide comment. As of this writing, we have not received a response.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Polina Sadovskaya, Director for Eurasia and Advocacy at PEN America, and Jane Buchanan, a consultant to PEN America. It was reviewed by Liesl Gerntholtz, Director, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center, as well as by PEN America’s Research team. The report was edited by Lisa Goldman.

The following experts on human rights in Georgia also provided expert reviews: Kety Abashidze, Senior Human Rights Officer at Human Rights House Foundation and Giorgi Gogia, Associate Director for Europe and Central Asia at Human Rights Watch. PEN America is grateful for their insights and input into the report.