This Q&A is part of a series of interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

For many, confusion and despair are natural responses to a phenomenon as daunting as climate change, and falling into conspiracy theories is often a byproduct of those emotions. The BBC’s Marco Silva works to arm people with facts to make sense of a changing world as peddlers of climate disinformation seek to exploit fear. Silva spoke about how he navigates such a fraught but important beat.

This interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

What kind of false narratives are you seeing pop up right now, and how do you keep up with them?

If you look on social media, you will find some people who still deny the overwhelming scientific consensus that climate change is real, man-made, and already happening. But, in recent years, other climate disinformation narratives have emerged. While accepting the existence of climate change, some people have begun deliberately spreading falsehoods in an attempt to delay climate action (for example, for financial or political gain). Some have promoted false and misleading claims about climate solutions. Others have used misinformation to attack climate scientists, reporters, and even weather presenters.

“Greenwashing” is another concept that audiences are becoming aware of. As corporate actors, for example, attempt to do their bit for the climate, they will sometimes make claims about the climate impact of their actions that are not actually backed by evidence. For all the efforts that reporters like me put into ensuring that the debate around climate change is based on fact, the tactics of those spreading falsehoods about climate change are ever-changing. This means that, in order to cover this beat effectively, reporters need to be very active listeners, keep close tabs on what is being said both on- and offline about climate change, and adapt, too.

A lot of disinformation, specifically election-related disinformation, plays at people’s fears and confusion. Is that true for climate disinformation? What feelings can purveyors of false information exploit when it comes to climate change?

As climate change manifests itself in our lives — for example, through more frequent and intense extreme weather events — it can be daunting to witness the effects it is already having on the planet. Fear, in that sense, can be a normal reaction to the news. In the face of such a threat, some people may find it easier, or soothing even, to embrace narratives that cast doubt over the science of climate change.

The fact that some of the science of climate change may not always be easy to explain — and understand — also creates fertile ground for misinformation to spread. Over-simplified explanations of complex phenomena may suddenly become appealing to some people. Others may feel so overwhelmed by the news that they, instead, despair over what they perceive to be a lack of action from politicians. Some even embrace a fatalistic view and decide, against all evidence to the contrary, that it is simply too late to do anything about climate change.This is a particularly powerful trend amongst younger generations – and one that I have reported on as part of my work. Without a doubt, fear and confusion are powerful emotions that those deliberately spreading falsehoods about climate change are keen to exploit.

How do you decide whether something is worth covering, or if covering it would just amplify misinformation?

It is fair to say that there is no shortage of wrong and misleading information about climate change on the internet. There is always a risk that, by reporting on a particular claim, journalists may attract more attention to it and thus spread it more widely.

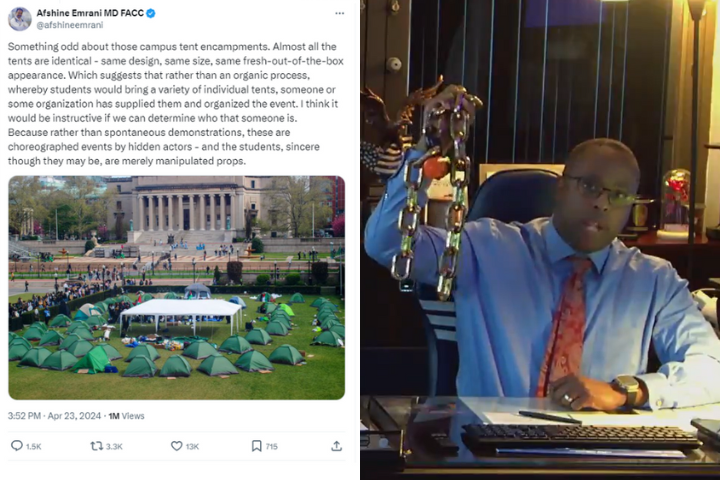

If I decide to look into a particular piece of misinformation, I will want to know that my reporting won’t be doing more harm than good, and that it will advance the public’s understanding of the topic, rather than further disseminate misinformation. A key test for me can be summed up by the question: Has a particular claim reached mainstream public debate? If a particular claim is simply circulating in Telegram channels devoted to conspiracy theories with a few dozen followers, I would argue that covering it may only attract more attention to it. But if the claim in question has reached a level of social media virality that means a sizable chunk of the audience is discussing it, if people are actively turning to search engines in big numbers to find more information on the topic, then there is certainly an editorial case to pursue the story.

What would you say is your biggest concern as a journalist navigating misinformation?

There’s a George Orwell quote in front of the BBC’s main building in central London, saying: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people things they do not want to hear.” As a reporter covering misinformation, I am at times accused of “stifling free speech” by some of the people promoting the very same falsehoods my reporting is meant to debunk. They see the work of fact-checkers and misinformation reporters like me as an attempt to “censor” their views and to “exclude” them from public debate. This could not be further from the truth.

By doing what I do, I am not trying to tell people what to think or to exclude anyone from public debate. As a journalist, I treasure free speech. My job is to provide people with the facts they need to make informed decisions and understand the world around them. If large swathes of the public are discussing claims that are not based on fact, my job is to step into the conversation, provide people with facts, and help them navigate the sea of information around them. It’s entirely up to them whether to engage with my reporting!

How do you maintain trust with readers as you’re covering something that might encourage them to remain so skeptical and distrustful?

I would say that transparency is key. If audiences are to trust my journalism, then it is important I show them how my reporting is done, what processes are followed, where my information comes from. To explain this point, I often use a phrase that many of us heard in math lessons growing up: “show your work.” It’s not enough to offer audiences answers if they can’t understand how we got to those answers. If you — as a reporter — are to be taken seriously, then it is important that you let audiences in on your journalistic processes. This can be achieved through simple actions: If you’re writing an online story, can you link to the sources of particular facts contained in your story? If you’re producing a documentary, can you incorporate your journalistic process into your storytelling? Have you considered opting for a story treatment that focuses heavily on how you got the story?

If your work is solid, then explaining it to your readers should not be a challenge – and they are more likely to trust you for it.

A lot of what we’re trying to do is talk to journalists about the election, but misinformation spreads in so many spaces. What do you think political and other journalists can learn from how misinformation spreads in the climate change space and how that is covered?

While there are some who, against all scientific evidence to the contrary, still deny the existence of climate change, surveys suggest they only represent a small part of the public. But, as I mentioned previously, in the place of clear-cut climate change denial, more subtle narratives have emerged. Fact-checking is an important journalistic technique — but, to effectively cover this beat, you will find that not all your reporting should be fast and responsive to trends. Slow and meticulous investigative reporting can be a major asset, too, especially if you are trying to find answers to bigger questions: who is spreading falsehoods? How are they spreading them? And why are they being spread? Combining rapid, responsive reporting with long-form, investigative journalism is important when trying to report on mis- and disinformation, whether or not it is related to climate change.

What advice do you have for journalists covering misinformation? What tactics really work?

First of all, I would say: Check your work once, twice, thrice, and then check it again. If your job is to tackle falsehoods, you want to make sure that your work is watertight and that your facts have been thoroughly checked.

Secondly, I would say: Listen to the experts! I have no scientific background, but covering climate change misinformation requires the ability to explain some pretty complex science to my audiences. I cannot do so unless I understand the science myself — and to do that, I have relied on the generosity of scientists and researchers who have taken my calls and answered my emails, often filled with incredibly basic questions about their fields of study.

One final point: Covering misinformation can take its toll on you and your mental health. Limiting my exposure to social media by setting times in my weekly schedule that are completely social media free has helped me keep my sanity!

Marco Silva reports on climate change mis- and disinformation for BBC News in the U.K. In the past year, he has investigated one of the largest methane leaks ever recorded. He exposed how a propaganda network on X whipped up support for a crude oil pipeline in East Africa. He also debunked claims that cloud seeding was to blame for record floods in Dubai.