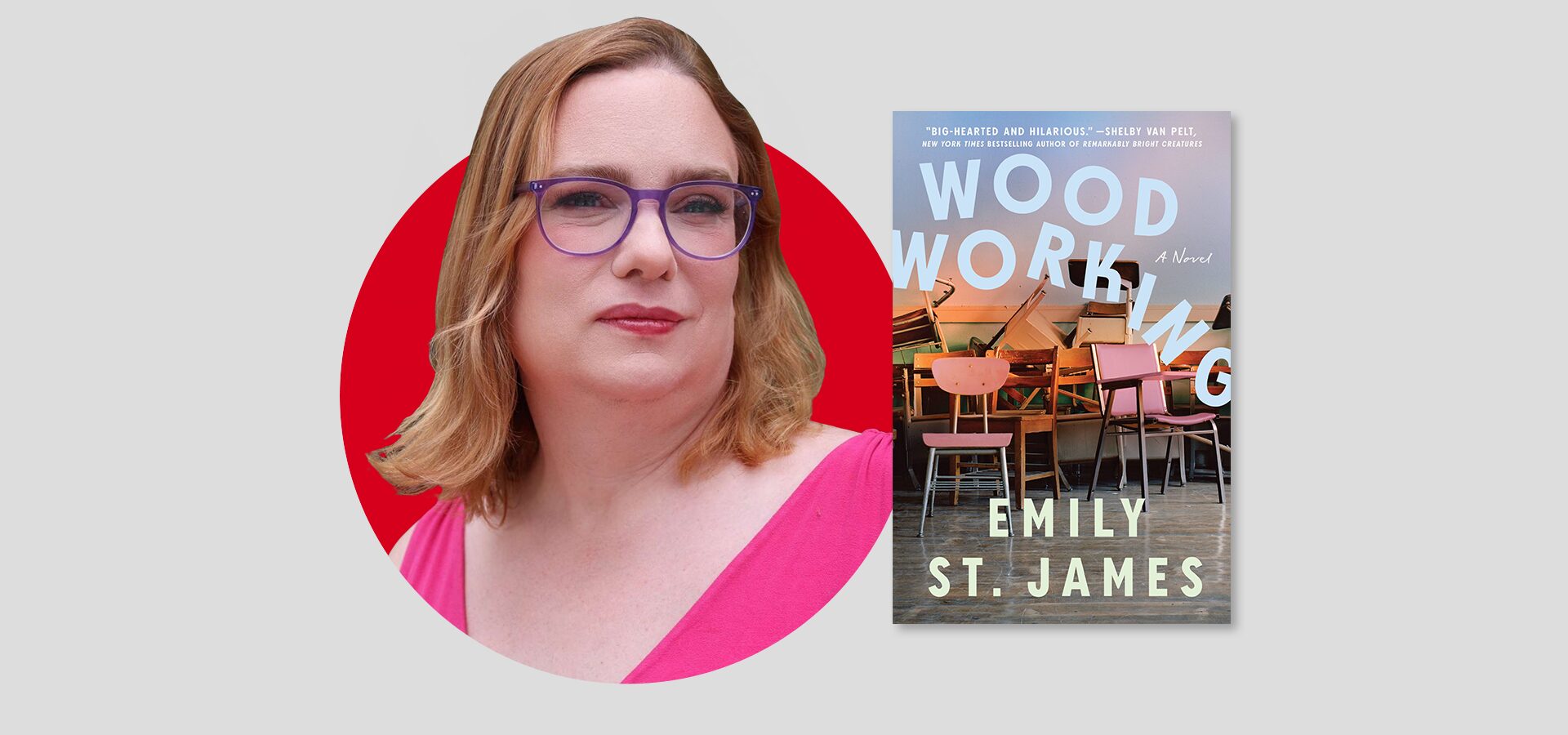

Emily St. James | The PEN Ten

In her debut novel Woodworking (Crooked Media Reads, 2025), Emily St. James interweaves the stories of two trans women, a student and her teacher, in Mitchell, South Dakota. Both coming-of-age in their own ways, St. James paints an unflinching picture of Erica, 35, and Abigail, 17, as they contend with the many forms of trans adolescence in the shadow of the first Trump presidency. With propulsive wit and unshakeable honesty, St. James debuts a novel unquestionably deserving of its place in the transfeminine literary canon.

In this interview with Claire Mehrotra, literary programs coordinator at PEN America, St. James discusses the many generations and forms of trans resistance and resilience, the current political moment of repression, and the radical hope engendered by unexpected friendship. (Bookshop) (Barnes & Noble)

The title of your book, Woodworking, is a term that may be unfamiliar to some. In your novel, Abigail describes the term as coming from the trans community in “the 1980s or whatever,” and meaning to “[disappear] into the woodwork.” Essentially, woodworking is to live life passing as cisgender and obscuring your trans identity. Why was it important to you to center this concept as the title of the book?

Early in my transition, I went to a Los Angeles trans support group in search of other trans people to be in community with. Near the session’s end, a wonderfully glamorous woman, probably in her 50s, spoke up. She had transitioned in her late teens, immigrated to the U.S., buried all evidence of her transness, and lived her life as a cis woman. She had a husband, job, and American citizenship predicated entirely on pretending her past didn’t exist. She started weeping about how lonely she was. I realized that she and I both wanted community with other trans people, even if we had different fears about what might happen if we asked.

A few weeks later, a support group attendee pulled me aside. “Is this you?” they said, holding up my male-presenting Facebook profile picture on their phone. I was somewhat well known as a TV critic, and they had read my work for years. I nearly cut my transition short on the spot. I had so much more to lose than I had imagined. My reputation as the steady sort of guy who knows things might collapse when I told the world that, actually, I had some personal news. The person at the meeting was quite kind, but I became convinced I was going to lose everything.

I didn’t want to stop being trans, but I wanted to not have to tell the rest of the world. Now, for the most part, if someone notices I’m trans, it’s probably the fifth or sixth thing they spot. (I have a very cute kid; they’re always the first thing people see.) Even if they read me as trans, I present in a conventionally feminine manner. They’ve usually sorted me into their enormous “woman” gender bucket before they get to, “Is she…?”

For the most part, nobody notices I’m trans at all. When I am out living my life, my transness effectively no longer exists. The early days of transition involve so much abrupt and unwelcome self-knowledge that I understand how tempting it becomes to disappear. As a public figure, I cannot go “deep stealth,” but I have a lot of sympathy for trans people who avail themselves of it, even if the endpoint of that choice might be weeping in a support group meeting after 30 years have passed in the blink of an eye.

We trans people do not owe it to our community to treat grocery shopping while trans as a radical act. We deserve the solitude of our own existences. But there is an intrinsic tension within the community between those moving past making their transition the center of their lives — sometimes by pretending it never happened — and those just embarking upon their own journey and desperately wanting someone to tell them it will be okay. Hence, Abigail (who’s so ready to disappear) and Erica (who really would love to copy off Abigail’s transition paper).

So many trans and queer stories are set in urban centers, like New York and San Francisco. Woodworking is set in Mitchell, South Dakota (much to Abigail’s chagrin). How did you come to Mitchell as the setting for this story?

I grew up in Armour, South Dakota, a tiny town an hour’s drive from Mitchell. So I knew the place well, and the state’s endless horizons and tiny towns huddling against the intemperate weather have always struck me as a great backdrop for something as internal as a transition narrative. What’s more, I sometimes think that too many believe trans people were invented in a queer studies lab at Vassar in 2015. Setting this book in South Dakota might push back against that pernicious narrative. Finally, setting it in Mitchell solved a plot problem. For the story to work, Erica could only know one other trans person (Abigail), which was a lot easier to believe in a town of 15,000 than in a major city.

One of the dynamics you explore in the book is the cross-generational trans experience. Throughout the book, we encounter trans women of all ages. What were you hoping to highlight by showing transness throughout the generations?

Woodworking follows trans women in their teens all the way up to their 60s, so it’s cross-generational in the traditional sense, but it’s also cross-generational in terms of “age” within trans time. Abigail is an “older” trans woman than Erica, even though the former is 17 and the latter 35. Transition is simultaneously a discrete event with an endpoint and something that persists through one’s entire life. Thus, I wanted to capture women at various stages of their “transition” beyond initial self-actualization.

Many trans people come out to themselves, then struggle to take further steps toward their most authentic lives, sometimes for years. Erica’s narrative is set within that penumbra. Similarly, there comes a point a year or two into transition where many trans people realize, “Hey, this didn’t fix all of my problems” and have to deal with other psychological and emotional burdens. Abigail’s story is all about her grappling with the scabs her transition ripped open within her family and community.

Being trans in an unwelcoming world has always carried a certain trauma with it, but that trauma differs from era to era. When Erica was Abigail’s age in the late 1990s, she didn’t examine her transness, because an entire culture had been built up to tell her how sick and wrong it was. In the 2010s, Abigail could transition more openly, because she existed in the brief window when society seemed on the cusp of broadly accepting trans identities. A trans person coming out in 2025 would have wildly different experiences from both of them. Writing about these different experiences of the world based on accidents of history feels vital to me in telling queer stories.

I sometimes think that too many believe trans people were invented in a queer studies lab at Vassar in 2015. Setting this book in South Dakota might push back against that pernicious narrative.

Something I found powerful in the book was that you never reveal to us Erica’s deadname. It is redacted in the text, and, in the opening of the book, she reflects that her “old name had come to sound like it was enveloped in fog. It was very far away from her now, somewhere out at sea.” What led you to this artistic choice? What impact did you hope for it to have on readers?

In the very first draft of Woodworking, Erica’s deadname was unredacted throughout, but I worried that leaned into one of the things I like least about the archetypal transition narrative, namely that the names we are given at birth and the names we choose create what are in essence two “characters.” The redaction served as a way around this problem. When a reader of the first redacted draft remarked that all of those boxes made her think of a hail of bullets, I realized I could use visuals to create a dissonance for the reader. Seeing a grey box where you are expecting a word trips you up for a second.

The biggest question around this ended up being a typographical one! In the original, the deadname appeared as a standard black box, like in a redacted government document. This was too jarring, and our wonderful designer ultimately mimicked the “fog” concept by using a slightly grayer box that suggested mist more than a moonless night.

One of the central relationships in the novel is between Erica, a so-called “baby trans girl” teacher, and Abigail, an out trans high school student. Schools are a key battleground in the current political discourse around trans people – fearmongering about schools and teachers indoctrinating kids into transness is a common thread. Did you have any teachers like Erica in your life? What brought you to highlighting a positive, affirming teacher-student relationship?

When I started writing the book in 2020, I could not have predicted how bad the political and legal battles to make schools an unsafe place for trans students would become. I sometimes wonder what these anti-trans bigots would make of Woodworking, which is about the terrifying prospect of a friendship between a trans student and trans teacher. Never mind that in my book the student serves as a trans mentor for the teacher!

Armour was a very small town. My graduating class was just 16 people, and I had only a handful of teachers. Nevertheless, at every stage of my education, I had teachers willing to encourage me as I tried to be a writer, even going so far as to read early work and offer notes. Did I have my own Erica Skyberg? No. But in the aggregate, I felt like my teachers cared deeply about me as a person and wanted good things for me.

As a culture we are too quick to assume that children and teenagers lack agency or the ability to accurately describe their emotional experiences. I’m a mother of a toddler, so I understand how tempting it is to filter my kid’s experience of the world through my eyes. There’s so much they don’t know yet. But I increasingly believe resisting that temptation is the work of being a parent. That’s why teachers are so important. They might not understand any one kid as well as that kid’s parents, but they understand children as a population and can see things a parent might miss. Erica cannot be Abigail’s surrogate mom — their relationship is too transitory — but she’s able to see pieces of Abigail the people who raised her will not. That’s worth celebrating.

This book takes place in the shadow of the first Trump administration, and captures the early moments of the rising tide of vitriol against the trans community. Now, in the second administration, trans Americans are facing more persecution and scrutiny than ever. What does it mean to you to create work that celebrates transness, especially against this sort of political backdrop of censorship and repression?

If you asked me if I could trade in my book for the adoption of a constitutional amendment that guaranteed trans people access to healthcare, housing, and other basic staples of existence, I would take that deal. (I might ask you to let me keep a copy.) I want my book to help people understand trans lives are vital and joyful, but I also realize what a drop in the bucket that is compared to building and maintaining the political will to support us. That said, art is one of the few ways cis people might start to understand and empathize with trans people. If my book speaks to even one person along those lines, then it will have been worth it a little bit. And if it helps just one trans person in a deep-red area feel less alone, then it will have been worth it even more.

Another backdrop to the book is a local election. Isaiah Rose, an establishment conservative, is running against Helen Swee, a democrat in a deep red district. It’s fascinating to read a narrative that contends with both local and national politics, especially as they pertain to trans people. It also shows student activism at odds with the overarching political tenor of the town, and resists oversimplification. What do you hope this novel could inspire in readers as activists? What do you hope your readers take away from this political story?

Trans literature is almost always read through a political lens by its very existence. That I have written a book that depicts a trans teenager simply living her life counts as a semi-radical statement at this point in time! I do not quite believe a trans person living as themselves is activism, but many transphobes act as though it is. So if Woodworking inspires more trans people to live honest and meaningful lives, it will have achieved its primary political mission.

I wanted to be careful not to write a book where the politics overwhelmed everything else, for fear of preaching to whatever choir might read this book. Yes, it’s centered broadly on people who are left-of-center, but they’re working to elect a woman they know will surely lose to her conservative opponent. It is very intentionally not a story about smart liberals winning over evil conservatives because life doesn’t work that way. Ultimately, the election serves as a useful backdrop to the story because Abigail and Erica are forced to care about it by dint of their identities. Thus, every time I wrote a scene that was directly political, I made sure it had immediate bearing on either Abigail or Erica, or ideally involved one of them making a deliberate choice that would illuminate their characters.

I do hope readers will realize just how badly things have trended for trans people — especially trans kids — in the U.S. since 2016 when the book takes place. The bathroom bill Isaiah sponsors and has vetoed is based on an actual 2016 bill that then-South Dakota governor Dennis Daugaard vetoed. Less than a decade later, Kristi Noem signed far harsher restrictions on trans people into law. Nothing had changed but the global right’s intense focus on us.

Art is one of the few ways cis people might start to understand and empathize with trans people. If my book speaks to even one person along those lines, then it will have been worth it a little bit. And if it helps just one trans person in a deep-red area feel less alone, then it will have been worth it even more.

Throughout the book, Erica is at work co-directing a community theater production of Our Town. The book contains several meditations on transness as performance, set against the backdrop of a literal performance. At one point, Erica’s co-director, Brooke, muses, “I wonder if he even knows that Our Town is representational and shouldn’t have a set at all.” What themes of Our Town do you see at play in Woodworking?

Our Town is one of my favorite things ever written. There is a non-zero chance that I plucked the name Emily out of the aether when naming myself because of Emily Webb in the play. She is, after all, a woman who realizes how much of life has passed her by only after it’s too late to do anything about it. In the book, Brooke calls this “the distance between a life as it’s lived and a life as it’s remembered,” and to say that has been a unique obsession of mine since childhood would be an understatement.

There is an unreal quality to Our Town that reminds me of a lot of trans art. In particular, it calls to mind Jane Schoenbrun’s brilliant 2024 film I Saw the TV Glow. Where Our Town takes place in a town devoid of setting but full of people, TV Glow takes place in a rich setting that is largely empty of anyone but its most central characters. In both, it is as though the world has been hollowed out and only a select few understand this. To be an “egg” — that is, a trans person pre-self-acceptance — is so often to feel like life is just a degree or two off from what it should be. Both Our Town and TV Glow literalize that in ways I find immensely compelling.

(Our Town also features one of my favorite queer-coded characters, cantankerous organist Simon Stimson, who delivers a heart-breaking monologue near the play’s end.)

In your acknowledgements, you mention other trans feminine authors who influenced you – you refer to Casey Plett, Torrey Peters, and others. Of Imogen Binnie, you say, “As far as I’m concerned, all trans feminine authors are standing on the shoulders of Imogen Binnie, whose Nevada is one of the great American novels.” What other books do you see Woodworking in conversation with? What books are on Erica and Abigail’s nightstands?

Abigail will read Nevada in her twenties and evangelize about it to everyone she meets. I expect Erica will read everything by Julia Serrano and Judith Butler and attempt to summarize their points for everyone she meets, potentially annoying everyone. I also imagine Erica having a lot to say about Will Arbery’s play Heroes of the Fourth Turning.

I hope that people find Woodworking to fit into the very small trans feminine lit canon. It has always felt to me most directly inspired by Nevada and Hazel Jane Plante’s Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian), another book about how powerful early trans friendships can feel. It’s also in conversation with the literature of the upper Midwest. The epigraph is from Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, a book which Woodworking reflects deep in its DNA. The book also has a lot in common with Tamsyn Muir’s Harrow the Ninth, a comparison that will make sense immediately if you’ve read both and will make no sense until then.

I hope people who’ve never really had to consider a trans identity as a lived experience before will read the book with open hearts. And I hope that trans people who maybe need a break will find a bit of respite in this book — while not thinking that it downplays the struggles we face in our lives.

Who do you hope finds this book?

There is an early Goodreads review (don’t worry; my wife reads my Goodreads reviews so I don’t have to) that misgenders Erica throughout but talks about how the book got the reviewer to think about the trans experience in a new way. That person isn’t my ideal audience for Woodworking, but I hope they’re part of it all the same.

This is a really difficult time to exist as a trans person. I dearly hope Woodworking finds those who have “ears to hear,” as the Bible would have it. I hope people who’ve never really had to consider a trans identity as a lived experience before will read the book with open hearts. And I hope that trans people who maybe need a break will find a bit of respite in this book — while not thinking that it downplays the struggles we face in our lives.

Also, I hope Taylor Swift reads it. I’ll bet she would think it was neat!

Emily St. James is a writer and cultural critic. This is her first novel. Her journalism and criticism have appeared in The New York Times, Vox, and The A.V. Club, and her writing for television has been featured on the Emmy-nominated series Yellowjackets. She lives in Los Angeles with her family.