Press play on any Works of Justice episode released since March 2022, and you’ll hear the stimulating vibrations produced by an orchestra of guitar riffs, piano, and low hums. In less than ten seconds, the instrumental from BL Shirelle’s “SIGS” sets the tone for the podcast, which features interviews with writers and artists reshaping the conversation on incarceration and justice in the United States. The song is included on BL Shirelle’s 2020 debut album, Assata Troi—the first LP released by Die Jim Crow Records.

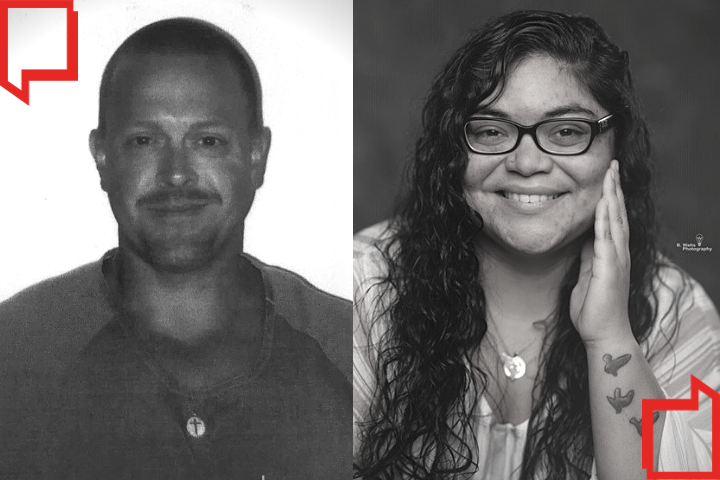

Transcending the often unseen and, or misrepresented, lives of people behind prison walls, Die Jim Crow has broken new ground as the first record label dedicated to artists impacted by the justice system. The project started out as Fury Young’s concept for an EP, inspired by Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010). Through recording sessions at the Warren Correctional Center in 2016 in Lebanon, Ohio, and with formerly incarcerated artists in Philadelphia and New York, the genre-breaking project stretched from soul music to rock and hip-hop as the musicians shared their struggles in and out of the justice system. Now, with the recent announcement of Shirelle’s promotion to co-executive director alongside Young, the record label and nonprofit lays the groundwork to continue its music making and advocacy initiatives for artists in prison.

“He sent me this very detailed, formatted syllabus of the album [and] what he wanted to be on it,” Shirelle said, describing how Young contacted her through an exchange of letters after seeing her performance at a 2014 TEDx event hosted in SCI Muncy, a prison in Pennsylvania. Young wanted to record music with Shirelle and presented her with themes such as minstrelsy, the war on drugs, and mass incarceration. “I just started picking out topics and writing mad songs. At one point Fury was like, you know, you can’t write the whole album, you gotta chill.” One of these early drafts would become “Headed to the Streets,” the sole single from the EP.

Despite early success recording incarcerated artists, Young struggled to gain the same access to other institutions that he had at Warren Correctional. Officials did not want to risk artists possibly speaking out about staff and living conditions within the prison. This changed radically in 2019 after he was cleared to work with musicians at three prisons in the South, recording over 20 artists. With this, the scope of his vision deepened to suit newfound possibilities.

“After I came back from that trip I proposed to the board that we were really becoming a record label, and nobody batted an eye,” Young said. “We had all these incredible recordings that didn’t have a home. If we become a record label, so many more people will have the opportunity to have their art put out.”

This also changed things for BL Shirelle, who had remained in touch with Fury Young after her release and was named the label’s deputy director. Now making her own trips to correctional facilities, she became responsible for artists other than herself, opening a new perspective on her growing role with community building at the label.

“That was a turning point in my career trajectory,” Shirelle said. “Before that I was more focused on being a solo artist, which I have every intention to do, but I realized that maybe this was a greater thing I could do that would make my community stronger. I shifted my focus to the artists I was working with ahead of my own career.”

Since artists are often transferred between facilities or released in the time between recording sessions and the release of their projects, Die Jim Crow artists took a more considered and ethical approach to building their roster. Artists are signed to produce individual albums, rather than being signed as performance acts with long term contracts.

“That’s just a way of not locking our artists in,” Shirelle said. “We’re Die Jim Crow man, we can’t continue the same systemic practices that have plagued Black artists since the beginning of time. They own 100% of the masters, all merch is split down the middle. That’s the example that we want to set.”

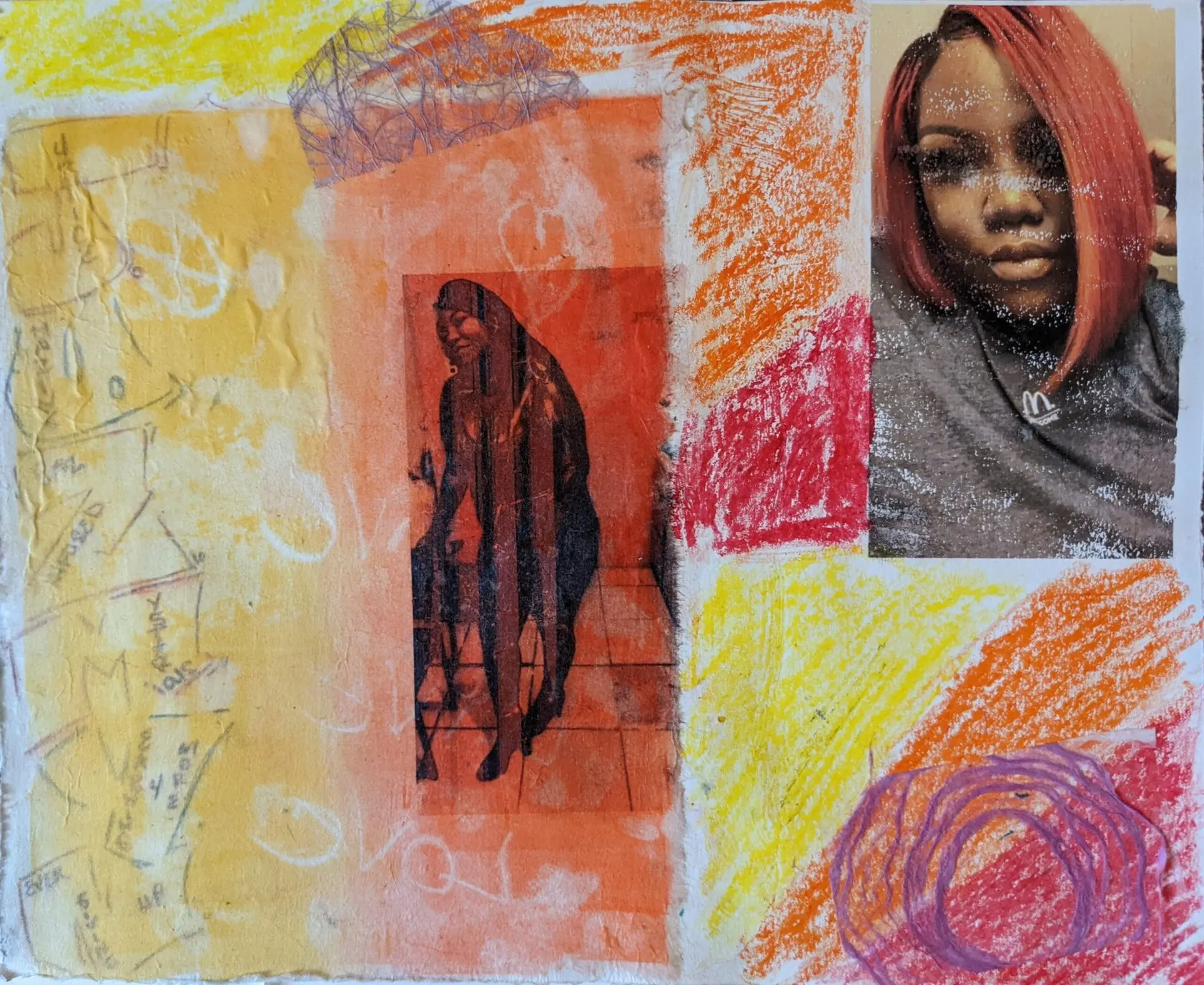

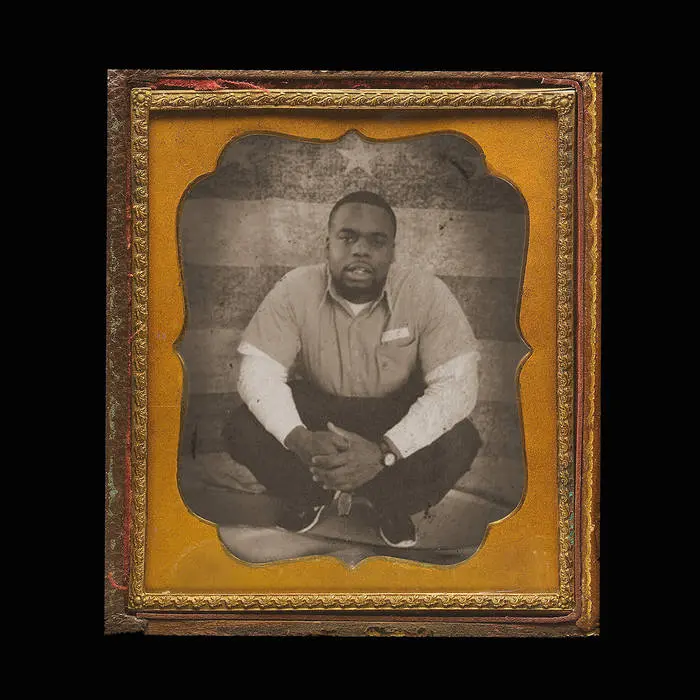

One of the most promising of those artists is B. Alexis, a poet and rapper from Conway, South Carolina. Having been incarcerated since age 17 and currently serving a 30-year sentence in the South Carolina Department of Corrections, hers is a story molded by violence and institutional failure.

One of the most promising of those artists is B. Alexis, a poet and rapper from Conway, South Carolina. Having been incarcerated since age 17 and currently serving a 30-year sentence in the South Carolina Department of Corrections, hers is a story molded by violence and institutional failure.

“She keeps a sense of truth and faith and self in her music that is very much needed in hip-hop,” Shirelle said. Her first single, “Black Barbie,” was executive produced by BL Shirelle is out now with an accompanying lyric video.

Because of the restrictions placed upon artists in prison, there can be lengthy waiting periods in the process of getting contracts signed and projects released. To mitigate these delays, the label has adopted a practice of “undersell, overdeliver,” in dealing with its artists. “The only consistency about prison is inconsistency. It’s a slower process and you need to come correct,” Young explained. “Word is bond on the inside.” This approach allows them to keep relationships intact throughout delays imposed by the carceral system as well as financial restrictions on the label’s end.

“Sometimes we go in and have no idea how we’re going to put it out,” Shirelle said. “We’ll record before we have the funds for mixing and mastering. But because the relationship is so thorough, we still get the benefit of the doubt.”

With her recent appointment as co-executive director, Shirelle manages an even greater share of administrative work, placing her in new territory, not only as an artist but as a justice-impacted person.

“For me it’s been quite the challenge,” she said. “It’s hard for me to put my admin cap on and then take it off and write a song, and I’m working on trying to find a better balance between the two, because in my professional position I still write songs for artists, I still executive produce for artists.”

Commenting on identity in the world of nonprofit work, where people from her background are scarcely represented, Shirelle said,“I look at myself as a person who don’t ask anybody for anything. The nonprofit world was just so different from where I came from and who I was as a person. So I had to separate my duty in the organization from my personal identity.”

“There’s a lot of hat juggling,” echoed Young. But despite their backgrounds outside of administrative work, both have found ways to use their position to further their personal and creative interests.

“I’m a writer, it’s just a natural thing,” Shirelle said. “But I didn’t realize that was a skill that I could take to lead a whole department.”

“Being on the Die Jim Crow EP, that was my first writing credit,” she explained. “Now I’m a primary writer on the contract being a justice-impacted person myself.”

As the label has grown, so has its programming. In addition to releasing music, Die Jim Crow launched the Instruments Into Prisons initiative in 2021, in collaboration with the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers, which has redistributed over 103 pieces of musical equipment into prisons as of the start of this year. The nonprofit also developed the PPE into Prisons campaign, raising $25,000 dollars to send masks into prisons and jails in 16 states.

Young’s vision continues to be a driving force behind the label. This is palpable in Tlaxihuiqui, the 2021 release by Territorial, a group of seven artists named after and housed at the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility. The album, blending indigenous chants, the blues, and hip-hop influences, holds the same broad scope and powerful messaging as the Die Jim Crow EP, conceived more than a half a decade prior. It has also laid the groundwork for several other upcoming projects as well, such as albums by Lifers Groove, a group made entirely of singers formerly serving life sentences, and The Masses, a hip-hop collective formed in a medium security prison in Florida. There is also a part two of the Die Jim Crow EP in the works.

“For me it’s always been about making great art. Revolutionary, groundbreaking art,” said Young. I definitely never thought that we would be where we’re at now, even up until 2019. It’s really the art and the people that drive me.”

Tomás Miriti Pacheco is a poet and journalist from Columbus, Ohio.