Banned in the USA Spotlight: Mike Curato

By Lisa Tolin

As a teenager, Mike Curato didn’t have any role models who looked like him. He felt like “a total freak.”

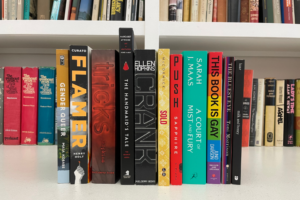

After publishing his graphic novel, Flamer, featuring a 14-year-old boy at summer camp coming to grips with his sexuality, he heard from so many people who felt the same. “The truth of it was, there were lots of people like me, all living, you know, in a bubble, where we just couldn’t see each other,” he said.

Flamer was tied with Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer: A Memoir as the most banned book in the fall of 2022 in PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans. It has been singled out by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and the book banning group Moms for Liberty, whose concerns include that it contains “alternate sexualities.”

What gets lost in that conversation, Curato said, is that Flamer is a book about suicide prevention. “This is a book about telling someone that regardless of how someone may disagree with who you are as a person, you still deserve to be here. There is a place for you, and no one has the right to take that away.”

In conversation with Jonathan Friedman, PEN America’s director of free expression and education programs, Curato shared what it’s been like to be at the center of the book banning controversy.

Could you tell me, why did you write Flamer?

I wrote Flamer because when I was Aiden’s age – that’s the main character of the book, he’s 14 – I didn’t have a book like this to sort of validate who I am. I didn’t have anyone in TV or film that looked like me, sounded like me, that had the same experiences that I had. I was a chubby, mixed Filipino Irish, Catholic kid. Who did I have to look up to? So I think it’s important to note that when you don’t see yourself in media, when you’re told that your sexuality is immoral, when you’re told that you’re supposed to look a certain way, and you don’t, when you see other people who don’t like look like you who you’ll never look like being lauded as the ideal, you start to think that you’re not supposed to be here. And it sort of incites a self-erasure.

I wrote this book because I want to help young people who are in the vulnerable place that I was in when I was their age. I think something that’s not often talked about during the banning of this book, is that it’s not a book about sex. There are, you know, a few pages with sexual leaning content. But there are hundreds of other pages. And it’s focused on identity and self-preservation. What doesn’t get spoken about in these PTA meetings, in the school board meetings, what’s not spoken about by these government officials who are pointing at this and calling it pornography, is that this is a book about suicide prevention.

I think that is so lost on all the people who haven’t read the book, who see a picture on the internet or have an idea in their mind. That’s what comes across so powerfully in the book, and you have the section at the end on suicide and suicide prevention hotlines, which is a fantastic resource. Talk to me about the positive reaction to the book.

What has been amazing is hearing from readers that the book has really resonated with. And there’s a whole range of ages that have gotten in touch. There are, you know, teenagers who have said, I am not out, I do feel really alone right now, but I have this book. Or, I am out, but I only have straight friends, and no one sees me like this book sees me. And then I hear from people my age — you know, I’m in my 40s — and they’re very emotional reading this book, because they never had this. And I’ve had people say, I’ve literally never been seen like this.

And what’s amazing about those connections is, when I was 14, I thought I was alone, I thought no one else is like me, and I was a total freak. And the truth of it was, there were lots of people like me, all living in a bubble, where we just couldn’t see each other. And we didn’t have things like the Internet back then. And we didn’t have these books, and we didn’t have movies that represented who we are. And so that fed into this sense of shame and not belonging. And now we have these things that can connect people who feel alone and are feeling desperate.

How did you feel about the negative reaction and banning of the book?

I am shocked and unfortunately not shocked. I had a lot of anxiety when this book was coming out, because I could see something like this happening. But then there was nothing for a year and a half or so. I think what’s shocking to me is I started to believe that we’ve made so much progress and that we wouldn’t go backwards. It wasn’t shocking to me that there is hate towards a book like this because I have experienced that my whole life, so I know it’s out there. I think what was shocking to me is that people care more about banning the book than trying to protect children’s physical lives in this day and age of mass shootings, for example.

And I think most people haven’t read the full book because then they would know, I’m trying to help someone. I’m trying to stop someone from taking drastic measures of self harm or suicide. And so that’s the shocking thing for me is that they’re basically telling queer youth, we don’t care about you, we don’t care if you hate yourself, and we’re just fine if you decide to end things. Because we’re more concerned about shaming you about your sexuality, shaming you about masturbation. There are some taboo themes that I addressed in this book that I’m sure some parents are uncomfortable with. But these are experiences that most teenagers go through. Some parents would prefer their children read about uncomfortable topics in a book because it’s a very safe place to learn. They can digest it at their own pace. They can put the book down if they want to. And then I think there are some parents that would rather just uphold a taboo and not talk about anything. And all that does is just perpetuate this cycle of shame.

Can you talk about the impact it’s had on you to see Governor DeSantis hold up your book?

I think the hardest thing for me, with all of the book banning, is thinking about the readers that don’t have access to the book that they need. I mean, this was the whole point, right? And I’m very scared for them. I’m worried about them. I’m worried about a kid in the middle of Texas, who isn’t allowed to read a book about themselves. I mean, what kind of damage is that doing to that child? And how much work are they going to have to do as an adult to feel whole, and accept themselves?

After that, the most frustrating thing is, this really interrupts my ability to work, which I’m sure is part of the design. I’m dedicated to continuing to make work like this. But it does take a lot out of me to see a news cycle in which my book is being slandered or lied about. And I know it’s unfounded when people call me a pedophile, or a groomer, or tell me I’m going to hell or, you know, make an actual death threat. That’s disturbing. People are disturbing. And it does take me a minute to regroup from that sometimes.

I mean, the thought of someone threatening someone else’s life, threatening my life, that’s a lot more disturbing than anything you’re gonna find in this book. My book also deals with a lot of toxic masculinity. And I feel like that’s what I’m experiencing right now. And it’s by no means only men who are saying awful things about me, but it’s that sort of culture of ‘I’m supposed to be a certain way because I’m a man,’ and I fail the test that these people have for me. And they’re scared to death of their child becoming someone like me. And the ridiculous thing is, there’s nothing my book can do to make someone’s child gay, right? If anything, it’s just going to validate someone who already is.

What’s next for you?

I am making more comics. I am working on my first adult graphic novel, which is called Gaysians, and it’s about the gay Asian American experience. I’m really excited about it. It’s coming out in 2025. And I’m working on my first middle grade graphic novel, which is still to be announced. So stay tuned.