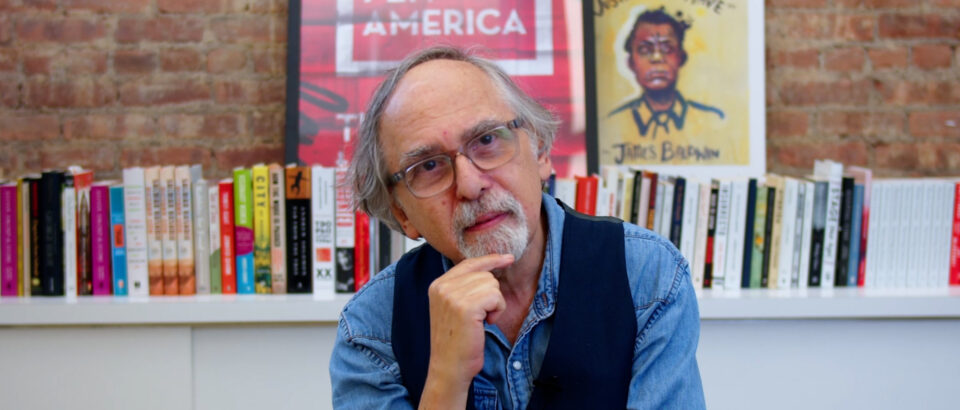

Art Spiegelman on Banning 'Maus'

Spiegelman reflects on fascism as third Missouri school district debates banning his Holocaust memoir

By Lisa Tolin

Art Spiegelman was shocked last year to hear that Maus, his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, had been banned in a school district in Tennessee.

Even more surprising was the rationale — not the violent history of his parents’ journey to Auschwitz chronicled in the memoir, but a single illustration of a “nude woman.” The picture depicted his dead mother in the bathtub after she committed suicide.

Spiegelman joked, darkly, that schools wanted “a kinder, gentler, fuzzier Holocaust” to teach to children.

Since that case in McMinn County, Maus has been banned pending review in schools in Florida and Texas, and reviewed in at least two Missouri school districts this school year over concerns that its availability could run afoul of a new state law making it illegal for a person affiliated with a school to provide minors with sexually explicit material. In one district, Wentzville, Maus was removed and then eventually returned to shelves. In another, Ritenour, it was permanently removed.

Now a third, Nixa, will vote next week on whether to ban Maus, too. At a board meeting on June 20, the district is slated to consider whether Maus should be removed as potentially violating the law, alongside two other books: a graphic novel adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Blankets, an illustrated novel by Craig Thompson.

Add your name: Tell Nixa, Missouri, that Maus belongs in schools

There’s obvious symbolism in the banning of Maus, even more so when you consider that it was followed by a bonfire of books in Nashville. Book burning was an early maneuver for the Nazis, and Spiegelman notes the Nazis first targeted the queer and transgender community.

Spiegelman said he wrote Maus to figure out his own history – how, in his words, he was “hatched” after his parents were supposed to be murdered. But he has come to recognize the importance of sharing that story with children. He reflected on the current book banning movement in conversation with PEN America.

What did you think when you first heard Maus was banned?

You know, I thought it was similar to the moment when I got a Pulitzer Prize, and I found out about it by mail. I said, that’s not happening, that’s some weird part of my dream life. Because Maus has become so firmly entrenched in schools. It didn’t seem like this was the kind of thing anybody would get up in arms about because even in McMinn County, people were reading it for many, many years.

Specifically, the complaint was about it being sexually explicit.

That’s where it got really surreal, when they decided it was sexually explicit, because anybody who could get their jollies off of Maus is probably in need of far greater help than anything the school could offer. And the fact that that affected the school board recipient, and is now an infection that’s spreading, it’s kind of shocking.

At first I didn’t understand what they were talking about. Because of the representation (in Maus) of the Jews as mice, when they stripped off their clothes, there was barely a way to see any genitalia. And then when I found out that it was described as a nude woman, not a nude mouse, but a nude woman, I realized it was about the section of the book that’s about my mother’s suicide, where she killed herself in a bathtub. It has a shape of breasts, but every kid must have seen a mother’s breasts at some point, even if they’re formula fed. There’s nothing there that could possibly titillate. Even if you’re a sadist, you wouldn’t go to that one for the picture, to see a dead body. And so I was offended just like they were, but I was offended by describing a naked corpse as a nude woman.

“I was offended just like they were, but I was offended by describing a naked corpse as a nude woman.”

I read the minutes of the school board’s discussion of Maus, and most people, it’s clear from their minutes, haven’t read the book at all. But they can still have eyeballs, they could see those images. Okay, so ‘this is a picture of nudity, so that we can prohibit, and this over here, this has a bad word.’ As far as they’re concerned, as long as they stopped short of saying we’re banning this because this history makes us uncomfortable, we don’t want our kids to be exposed to these things, they’re on safer ground.

Do you think it’s really that the history makes people uncomfortable?

Of course! It’s an uncomfortable history. It’s a painful history. In Maus’ case specifically, I think, first of all, I think it was a drive-by shooting because it wasn’t really aimed at, “We shouldn’t talk about the genocide because they’ll know we want to do it again” or something. But it’s because Maus has two aspects. One is a very detailed history of what I could glean off my parents’ past, brought into the context of my relationship with my father now, as I’m getting that story. That’s very granular, very specific. The more honest and intimate you can be, the more it becomes universal even if it’s not your experience. But the other aspect is, the fact that every character in the book is wearing an animal mask makes it kind of universal. It has an aspect of fable, fairy tales, funny animal comics like Donald Duck, and ultimately, Aesop’s fables. And so that makes it general.

And so no matter how specific the information is, it’s about what it means to dehumanize someone, to project otherness onto them, the othering of people. It could be anywhere. And the main thing that happens is, as we’ve seen in the past, with the Nazis, the very, very first people that were victimized by the Nazis weren’t even Jews, they were the “sexually deviant.” It’s about such a macho culture, the idea of “I am the master race, I am superior to you, because white lives matter” or whatever. And as a result, what was gone after was transgender people, queer people of various kinds. That’s where they focused their murderous intent as soon as they came into power.

So that was where they started. And that seems to be the hot button in America right now. We haven’t learned much from the past, but there’s some things you should be able to figure out. Book burning leads to people burning. So it’s something that needs to be fought against.

“We haven’t learned much from the past, but there’s some things you should be able to figure out. Book burning leads to people burning. So it’s something that needs to be fought against.”

The Nazis obviously banned books. What does it say to you that book banning is now happening here?

I think that book banning is not the only threat. I mean, there are many threats right now, where it seems to be, memory is short, fascism is a while back, they don’t know much about it. And, you know, it’s maybe attractive. It’s so complicated to live in a plurality, a democracy of some kind, even if it’s a flawed one, and try to balance out all those needs, and make decisions for yourself. So there’s a desire to keep it simple. And maybe fascism looks simple to them. And it seems to be the direction we’re moving in, more and more in various ways. And not just in America. It’s a worldwide phenomenon.

Why do you think graphic novels and comics particularly have become easy targets?

There’s something about pictures. Pictures go straight into your brain, you can’t block them, right through your eyes. You see it, you can’t unsee it. With words, we’ve actually got to struggle to understand the word before you can be puzzled or surprised or enlightened by those words. But now, we’re living in such a visual culture. The amount of visual information that comes through your screens is enormous, and there’s no way to screen out those screens.

Pictures are such a threat that my first awareness of book banning was, my medium was under threat. Just about the time I was five or six years old, there were comic book burnings all over America, supported by clergy, teachers, librarians, parents, politicians and psychiatrists. Psychiatrists in fact led the charge saying that these comics are barbaric, and they’re ruining our children, they’re sub-literature, and it led to Senate hearings about comics.

That comic book burning resulted in a self-censoring board that decided what could be shown in comics and whatnot. They make most comics, either anodyne or unintelligible by taking out the possible threats to the Comics Code. That lasted for 30, 40 years; comics were almost wiped out. So basically, it’s because pictures are so strong, it’s words and pictures combined, they’re actually stronger than either one alone. And it’s easier to take information in and study. Unlike a movie, comics stand still. So you can look at a picture that some school board that never read the book pulls out of context, and says “kids are seeing this!” They are seeing it, they may even look at it longer, they may have questions about it. Better that those questions get dealt with, and that’s the job of schools.

Why do you think it’s important for kids to know this history?

The smell of authoritarianism and even Fascism is really in the air right now. And it’s in a lot of places, even in very democratic countries like France, the right is moving way up. It’s back in Germany, in countries like the Scandinavian countries as well as in South America and God help us, in America. So it’s important to understand what happened.

You have to learn to overcome that thrill of going, I’m better than you, because I’m part of that “in” crowd, the majority, the ones that we will not let a minority replace us. All of that bullshit, actually, that’s part of this current wave of things is a way of actually domesticating that majority to make them lose track of their own actual interests. Because even from post civil war, the immediate thing was to re-disenfranchise black people, right after slavery was abolished. And therefore, leave white people feeling like, well, you know, I don’t have a pot to piss in, but I’m better off than that blankety-blank over there. And that makes you feel like you’re part of that master race, even though you’re really being controlled by big money, by forces well beyond your control. And that gives you your scapegoats and that scapegoating is a long history, a long, long history and it’s allowed for terrible things to happen throughout that history.

What would you say to the parents who are saying these types of stories are making our children feel guilty?

Parents who want to protect their children, by not making them feel guilty because great grandpa was a Klansman aren’t protecting their kids from anything. In fact, the great thing about books when they go into curriculum is they get discussed. I don’t care what they teach, if they want us to teach The Turner Diaries, Mein Kampf, it’s okay, much better that it be taught in a school context, where you can actually understand what it’s telling you, what’s manipulating you into believing, is much better than finding it on dad’s shelf and going, “Oh I see, there’s a race war we have to fight.”

It’s better to have these things in context. This is not to say schools shouldn’t have any supervision from their parents. If anything, we should have more participation from their parents in what they were studying in school. But we have to allow the schools to determine that primarily. It would be like if they went to the doctor and said, I’ll take three OxyContins and a couple of these Wellbutrins over here. It’s not the best way to keep your kids healthy. We have people trained to try to make exactly that happen, and one should allow them to do that.

What would your dad think about what’s happening now to Maus?

You know, I sometimes wonder about that, because I chose not to portray him in an idealized way. Usually most of the Holocaust narratives, I would find, are about the sanctification of the victim. They suffered, therefore, they become ennobled, and that’s what the story is. That’s such bullshit. Suffering only causes suffering. I’ve now met a spectrum of survivors in the course of my life. Some of them indeed became much more thoughtful human beings, some came through with all their prejudices intact, some came through very damaged. And I wanted to make that part of what I knew about my father and not whitewash it.

The thing is, that notion of suffering is a very Christian notion, that somehow you’re ennobled by it. And bizarrely enough, the word that has come to cover this aspect of history is called the Holocaust. And that’s a problem for me. It’s a phrase that I think Elie Wiesel introduced that replaced a perfectly serviceable word that was invented because of the Nazis, which is called genocide. And the Holocaust just means “burnt offering.” My parents didn’t volunteer to be offering.

And that’s just leaving me in this awkward position of Maus the Holocaust comic. I don’t like the word “comic” and I don’t like the word “Holocaust” and here I am, folks, while I’m talking to you, I’m no longer a cartoonist. I’m just playing one on television.

What do you consider yourself instead?

Neurotic. A neurotic cartoonist.