This Q&A is part of a series that will include interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

As a reporter who spent years covering disinformation and online manipulation, Jane Lytvynenko knows a thing or two about how these campaigns have evolved. She’s applied that knowledge to covering how disinformation has impacted the war in Ukraine, U.S. politics and the business world. Her work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, the Guardian and elsewhere. Previously, she was a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, where she probed global media manipulation cases and helped to train newsrooms. Lytvynenko was also a senior technology reporter focused on disinformation at BuzzFeed News. She is currently working on open source investigations and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In your coverage of Russia’s war in Ukraine, how are you seeing disinformation campaigns play out? What have you learned about covering disinformation in this space?

Disinformation is part of basically every global event at this point. It’s something that governments or bad actors use to try to rally support for whatever it is that they’re carrying out, and Russia is definitely no exception to that. So when it comes to Russia, there are a few different ways we can look at the propaganda that’s coming out. One is, it can be potentially useful for reporters to try to understand what’s going on within Russia, or what’s going on within occupied territories in Ukraine – and also going on on the front line – because Russia sends its own propaganda correspondents to the front line. There’s still immense amounts of video, from both the front line and occupied territories – propaganda videos of Ukrainians imprisoned by Russia that allow loved ones to find them; videos of children Russia has taken from Ukraine and then put into adoption or reeducation camps. There’s still an immense amount of information on social media. Even when it comes from an aggressor state known for successful propaganda work, that kind of evidence can be immensely useful in investigations.

Russia also uses disinformation to weaponize or to basically inoculate domestic audiences in support of the war. It’s also used propaganda in the European Union and in the U.S., and really, globally, to try to cause societal divisions and undermine support for Ukraine. I think every reporter who covers this war has to have propaganda, media manipulation and social media disinformation campaigns front of mind.

You mentioned social media. This war was sometimes referred to as “the first social media war.” How do you navigate the rapid-fire spread of information on social media? How can journalists use it to their advantage?

I would really like to push back against the claim that this is the first social media war. Some of the most important skill sets that reporters have learned over the past, you know, 10 to 15 years come from the war in Syria. Syria was one of the first where social media-gathering and evidence-gathering played a really important role. And even during Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014, we saw social media and disinformation campaigns play an incredibly important role, including during the annexation of Crimea. What I think happened on Feb. 24 (when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022) is that reporters began putting into practice a lot of accumulated knowledge in a really concentrated way. That also includes knowledge gained during the pandemic and working with social media information.

I think reporters who look at the war in Ukraine, for many, social media is sort of the first stop. And that’s because social media is really a central place for evidence in conflict. Now, that’s changed with the progression of the war. Early on, before parts of Ukraine were occupied, Ukrainians were not afraid to post evidence to social media or to interact with reporters from occupied territories. That’s changed pretty significantly. But I really just don’t see how anybody can cover the war in Ukraine without understanding the social media aspect of it, which is pretty varied and pretty wide. It’s also a war where we saw TikTok and Telegram become some of the key social media networks that reporters are looking at.

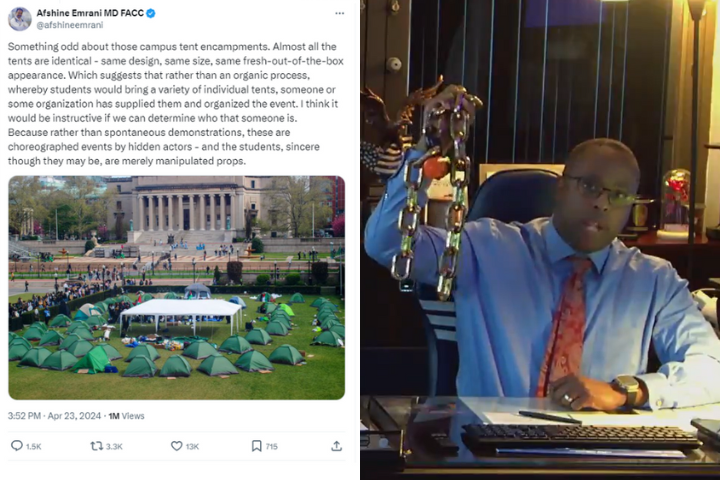

A key point seems to be that misinformation narratives and disinformation narratives and the way they spread are not new. You covered the way disinformation was creating conflict within communities in 2020, in health care, race relations and politics. What do you think has changed since 2020, in terms of how disinformation is spread, and how do you think disinformation will affect the 2024 election?

When I first began covering disinformation back in 2016, there was not a lot understood about the way that it traveled across social media platforms, including by social media companies themselves. We had never really paid close attention to how their platforms would have been misused until U.S. media and Western media coverage began investigating it and pointing it out. And during much of that time – although imperfectly, and maybe not always in ways that those who studied the field recommended – social media companies did try to address some of the shortcomings of their platforms.

If we look at 2024, eight years later, that has really changed. Many social media companies are no longer working with academics or researchers. They’re not always responding to critical coverage. And there has also been – outside of social media networks, particularly in the U.S. – a concerted focus to try to halt research into the way social media networks function. What I think that means is that, although the stopgap measures that we had four years ago or eight years ago were imperfect, now there are many fewer of them. And, of course, we can’t know the effect it’s going to have on the 2024 election, but certainly we know that it’s going to be, just like every other election, a time when disinformation and misinformation and propaganda will flood social media networks. Without research, without stopgap measures, without trust and safety teams – like in the case of X (formerly Twitter) – it’s going to be really difficult for folks who use social media to rely on the information that comes from it.

What do you think journalists can do about that? How do you think they can best arm the public with the right information?

Journalists are not advocates; the job of reporters is to try to cover platforms or disinformation campaigns as they are. It’s up to regulators or social media platforms to act on that information. I think for reporters, it’s really important to try to understand how disinformation moves through social media networks, and not only focus on those really big disinformation and propaganda campaigns that target national communities, but also look specifically at their own small communities, because one of the things that we know about online manipulation is that the purpose is not always necessarily to mislead – the purpose is to divide.

When reporters look at their own communities, it’s important to identify those points of division and see whether any manipulation campaigns are targeted at those points of division. It’s not always going to be the big national or international stories that are effective; it’s going to be the local stories that live in local Telegram groups or WhatsApp groups or Facebook, or what have you. I would say for journalists, looking at their own communities is key.

Something I think makes that hard is the lack of trust people have in the news, whether it’s local or national outlets. So, especially when covering disinformation, which might encourage people to be even more skeptical and distrustful, how do you build that trust?

There’s no silver bullet to reward building trust with the community. It’s a slow, arduous process that can crumble in a second, but it can take years to build up. We know that a big part of the distrust in media is the outward attacks on media. We know a big part of it is the disappearance of local news and the increased reliance on social media. But one of the things that reporters can do is really try to show their work and how they got to their conclusion, especially in the field of disinformation. If a reporter is doing a fact-check, it’s not enough to just say, “this is false,” or “this is true.” Explain to your audience how you got to that conclusion.

But more than anything, I think it’s important for reporters to explore the effects of manipulation and propaganda, and not only rely on what’s a fact and what isn’t a fact. Our job is to tell stories in a way that our audiences can rely on and can understand how we got to those conclusions. One of the approaches that I think is most effective is using open sources of information. So when we cover the war in Ukraine, for example, if we do an investigation that involves using social media content or databases, we explain why that social media content points to this. We show our evidence and we show our work. That is certainly one of the ways that reporters can try to earn the trust of their community. But it’s a really big problem that is going to take an immense amount of work to correct.

When covering disinformation, or just encountering it no matter the beat, what has been the most challenging situation you’ve been involved in? Have you ever received any blowback for your reporting on disinformation, and how did you handle it?

I think one of the most difficult things about being on the disinformation beat is that, very frequently, harassment goes hand-in-hand. That is a reality that reporters across beats face, but on the disinformation beat, particularly. Personally, I have had really unpleasant situations where the harassment after a report or fact-check or investigation would get so bad that it was genuinely unsettling. So this is really a place where reporters need to consider personal safety and personal guidelines, but also, newsrooms need to be able to take care of their reporters. Newsrooms need to have clear policies for what happens when a reporter is under a harassment campaign or is attacked. And it’s up to them to set up adequate security guidelines and security training for reporters, especially ahead of the election, when harassment campaigns will almost certainly be causing tension.

Disinformation is a big topic that can be so overwhelming for people, especially for younger journalists. What advice do you have for younger journalists who are nervous about covering this topic or don’t know where to start?

Make sure that your online presence is controlled. Make sure that your online security is tight. The worst time to try to lock your door is when somebody is trying to break it down, so make sure those locks work. In terms of broader coverage, I would say two things: One is, try to use tools that allow you to utilize the open source investigative skill set as much as possible. These are things as basic as understanding how to do reverse image searches across search engines to understanding how to look at a satellite image. All of those skills are better learned ahead of a crisis or a breaking news situation than during a crisis or a breaking news situation. But also, those are the skills that are going to help you tell stories in a really transparent and evidence-based way for your audiences.

The final piece of advice would be to not forget that you’re a storyteller. I think on the disinformation beat, fact-checking plays an important role, and an immediate response to disinformation plays an important role, but the bigger story with disinformation is the long-term effects it has on our communities and our societies and our systems of governance. My advice would be to not forget about those long-term effects, to do those investigations and tell those stories, because those are going to be the most impactful types of stories that you do on this beat or any other beat.

Is there anything else you want to say that you think I missed? Anything you’re afraid of on this topic or that you’re hopeful for?

I think with every global or local crisis, we see the power that disinformation and online manipulation has. I really hope that reporting on this beat continues. I really hope that those who cover this beat on a regular basis do so creatively, and do so with an eye to the future and an eye toward compelling stories, because I think that is going to be the best way to address it.

(PEN America runs a digital safety and online abuse defense program for journalists, including training for journalists and newsrooms, short videos on how to protect yourself from doxing and hacking (Digital Safety Snacks), and a comprehensive guide on navigating online abuse (Field Manual).)