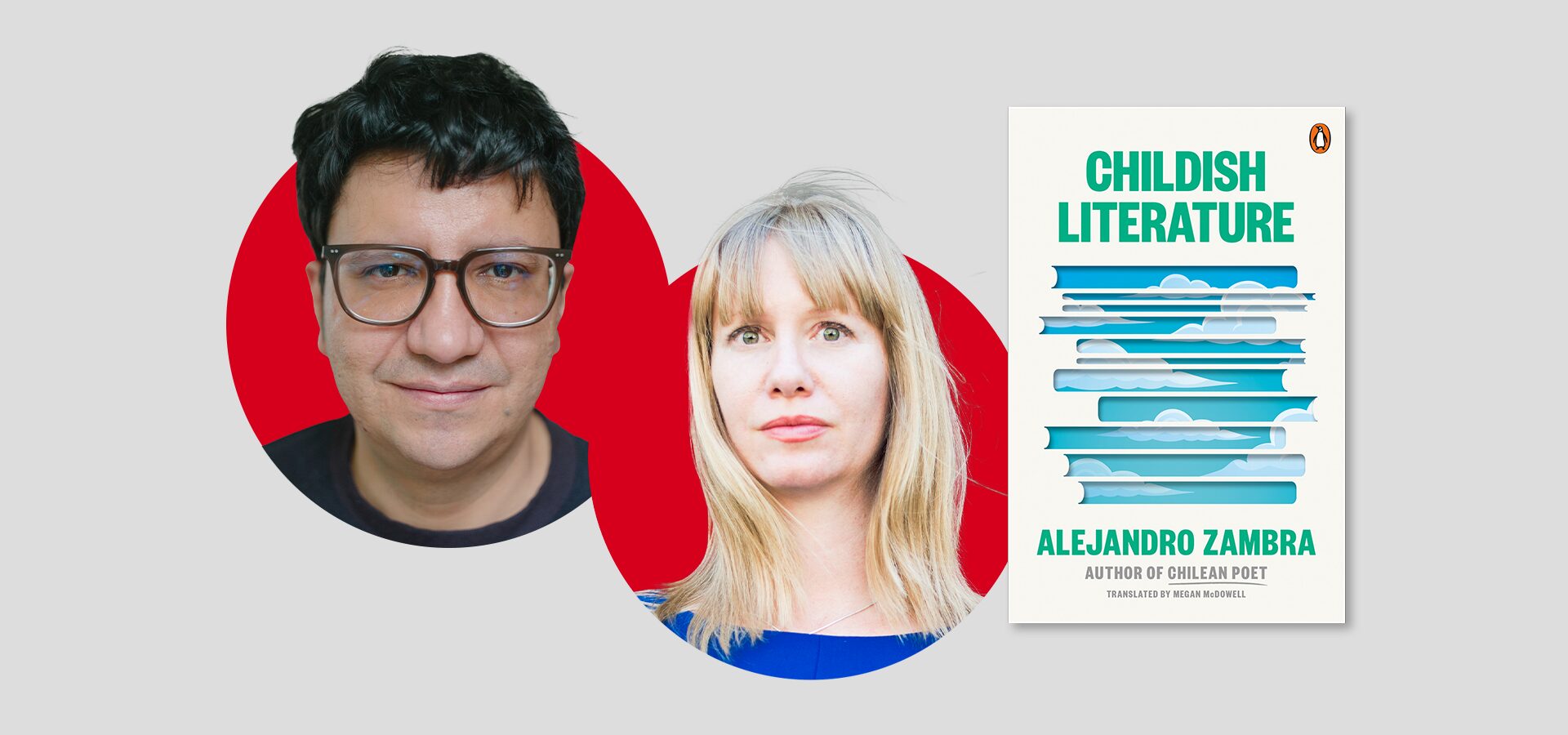

Alejandro Zambra’s new collection Childish Literature (Penguin Books, 2024), translated by his long time translator and friend, Megan McDowell, combines short stories, essays, and poems around the theme of fatherhood to explore this life-changing experience in a way that captures it in all its complexity. Unveiling his childish side, Zambra reveals what he saw for the first time through his son’s eyes in prose, shining in McDowell’s translation, that is at once poetic and personal, playful and philosophical.

In conversation with Amulya Hiremath, Communications Consultant for PEN America, author Alejandro Zambra and translator Megan McDowell offer their insights on the creative choices they made, how to work with such a personal subject, and why language is key to preserving memories. Zambra’s interview responses were translated from Spanish to English by McDowell. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

Childish Literature is a collection of various types of literature–essays, short stories, and poetry. How did working across forms capture the breadth of experiences that are fatherhood? How did you decide which ideas and stories were better served as fiction and poetry and which were better served as non-fiction?

AZ: I don’t decide beforehand whether I’m going to write a poem or a novel or a trip hop-based tango… I tend to simply start with an image that for some reason attracts and obsesses me. Writing is for me much more like a walk with no fixed destination than a 100-meter dash. In this book, all those initial images arose in the first months of my son’s life, especially in those first weeks when night and day are indistinguishable for the baby and therefore for you and your partner. So you live in a perpetual semi–awake state, like the surrealists wanted… All the pieces of this book had their origin in the rocking chair, so to speak. Suddenly, with the child sleeping, new memories came, or sensations of new memories, which I would write down or whisper into the phone. Even a story like “The Kid with No Dad,” —which, along with “Skycrapers,” are the pieces in this book that can be most fully understood as fiction— has its origins in the rocking chair. I was there with the baby on my chest, and I suddenly had this terrible memory of sitting on a bench with other children, at seven or eight years old in the school’s crowded playground, watching the older children fighting and shouting while I was eating my bread and avocado. It was an everyday scene that now I swear happened many times in that exact way, but I had never remembered it before. So perhaps it is a false memory, who knows. What is not false is that violent atmosphere of a boys’ school, the fights at recess that ended with noses dripping blood, and which we painfully understood as some sort of stupid masculinity contest. And of course thinking about that scene abstractly is very different than thinking about it with your little son sleeping in your arms. That same day or a few days later, walking through the neighborhood with my baby, I came across a very loud and belligerent little dog, and I remembered my fear of dogs when I was a child, how important that fear was throughout my childhood. So those were the starting points of a series of thoughts about fear and violence between men and about the difficulty we had in establishing lasting bonds of trust, of true friendship, that led me to write that story.

You discuss how the writer Baudelaire parallels the artist and child when he defines artistic genius as “childhood recovered at will.” You write, “More than remembering or relating, a writer is trying to see things as though for the first time.” (page 6) What were some of the things that you saw for the first time through your son’s childhood? How did writing about it help you process this phase?

I have always liked how Baudelaire compared artists to children, and also to convalescents who, after being near death, experience life again as though for the first time. In this sense, a father or mother is always a convalescent, a beginner. We forget precisely that early childhood, those first years of our lives that we later witness as parents in our children’s learning. We do not remember the time when we didn’t know how to speak or walk, and witnessing those processes in our children’s lives is wonderful, decisive and moving. Mothers, fathers, older siblings, uncles, grandparents, all the people who have had the incredible opportunity to accompany, for example, a kid’s acquisition of speech –my God, those first steps, those first words, those days when children know four or five words and with them they manage to name twenty or thirty things. Or when they learn to tell jokes, or when they use language for the first time in an ironic sense. My son’s birth changed everything from the roots, and the truth is that I also have the feeling of having learned to speak and to write again thanks to him.

I became a biological father at 42 years old, so I belong to that very small group of men who had the opportunity to think deeply about fatherhood before freely deciding whether or not to have children. It was a valuable opportunity, which also allowed me to form an idea of fatherhood that didn’t not depend solely on my experience as a son. I was able to see how friends, men and women, changed when they became parents; I was able to accompany them, I was able to learn from them.

You compare the way women pass on the knowledge of maternity to the way fathers fall short in passing down their knowledge of paternity; “Our fathers tried, in their own ways, to teach us to be men, but they never taught us to be fathers. And their fathers didn’t teach them either. And so on.” (page 4) Is this book your way of teaching your son something about fatherhood? Was there anything you wanted to share with him through the book, but failed to capture through words?

He will certainly be able to decide in the future whether or not to read this book, which for me is more of a script or a draft for the conversations I hope to share with him when he grows up. I have to say that for me being a father to this particular boy has been pure joy and learning. But of course I am not saying that parenthood is easy, of course it’s not, the worries are endless and varied. Maybe kids give us more hope than we are able to give them. I think this book is hopeful and realistic, two things that are not exactly easy to reconcile—what with all of the wars, genocides and climate crises, optimism is not exactly the order of the day. Sooner or later all parents have to find a way to guide their children through the minefields of all of those devastating things, but we hope to approach those conversations with a spirit of compassion, empathy, and openness.

A large part of the book is also a dedication to your father and how he shaped your childhood and upbringing. Why did you think it was important to bring in that thread of generational connectivity and continuity? What do you hope your son will learn from the dynamic you had with your father?

Well, they have their own relationship and I am very grateful for that. Both «Blue-Eyed Muggers» and «Late Lessons in Fly Fishing», the last long pieces of the book, came about when the book was almost done, and they transformed it, although it already was a book about fatherhood and masculinity. In different ways, those pieces relate to the moment when my father became a «present» grandfather to my son, and I use quotation marks only because he lives in Chile and I live in Mexico so it wasn’t easy for my father to create a presence. One day he started calling him every Saturday and Sunday morning, not just to ask how school was going, but in order to spend a full hour playing very abstract games I don’t totally get while we make breakfast. So every Saturday and Sunday my son waits for those calls, and they have fun. We grew up with this feeling that our parents were inaccessible and only payed attention to us when we started behaving like adults, but sometimes, when I hear my dad playing with my son, I think that that feeling might have been unfair, the same way that in the future I might think that things my son says about me are unfair. I can certainly imagine how hard it has been for my father to accept his own son’s constant questioning. Also, many Chileans who grew up in a dictatorship one way or another associated the word father with the word dictator, so we created our sense of identity by deeply interrogating the inherited idea of authority and the idea of family. But there is one thing that has always been present between my father and me: love. And I think my son already clearly perceives that. I became a biological father at 42 years old, so I belong to that very small group of men who had the opportunity to think deeply about fatherhood before freely deciding whether or not to have children. It was a valuable opportunity, which also allowed me to form an idea of fatherhood that didn’t not depend solely on my experience as a son. I was able to see how friends, men and women, changed when they became parents; I was able to accompany them, I was able to learn from them. I can never thank them enough for sharing their hopes and uncertainties and deepest fears with me.

I’m not against photos or videos, although I think literature always seems less fixed, less definitive, more subjective, and therefore better communicates what tends to fade away over time. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but writing is what I do, so I’m passionately writing those thousand words anyway.

In the final essay, ‘Late Lessons in Fly-fishing,’ you write, “The experience of fishing functioned in a decidedly similar way to literature. For those couple of days, our languages coexisted. What I mean is: we coexisted, it worked.” (Page 196) Has literature helped you coexist with your son? How important is using language to preserve this precious phase of life rather than photos or videos?

My son’s mother is Mexican and I am Chilean but we are both writers and the territory that we share most fully and intensely is literature. We never discussed it, but we were in complete agreement that we did not want our son to grow up hating literature. He knows that literature is our work, but we have tried to make him see that our work is not his enemy, we have tried to show him that what we do is done out of passion, that we like it a lot, and that he can participate in that work, that it is not a forbidden or inaccessible territory for him. He has grown up in a house full of books, and every night of his life his mother or father or grandmother or step-grandfather -who are painters and who live next door and are utterly important people in his life– have read with him. So far –he is six years old, but I am sure that he would ask me to say that he is almost seven– his childhood has been, in this sense, very different from mine and more like his mother’s, because I grew up in a house without books or bedtime stories, but I was lucky to have a maternal grandmother who instilled a passion for writing in all her grandchildren. I never saw her with a book in her hands, but she always gave us notebooks and pencils as a gift and wrote poems and songs for us and encouraged us to keep diaries. And, since she was the funniest person we knew— perhaps the only truly fun adult we knew—we liked writing, and then later we liked literature. So thanks to her, writing was, from a very early age, a habit and a game, and I think that even though I can now say that it is my work, it has never stopped being a habit and a game. So perhaps watching my son grow up I have finally understood that my true role model is my maternal grandmother… As for the second part of your question, it is such a significant topic that could lead us to endless discussions of what kinds of knowledge emerge from literature; I think in one way or another, every piece of writing includes that question. A great deal of my work comes from looking at photos and imagining what was around: who took this photo, why this person is there, and why other people weren’t. I don’t think I’m alone in having played the melancholy game of imagining what those photos didn’t show, but I only had a few images, the entire archive was small, so the blank spaces were huge. My generation’s children are going to play that same game differently, considering the many gigabytes of videos and photos we’re saving for posterity. Of course, I’m not against photos or videos, although I think literature always seems less fixed, less definitive, more subjective, and therefore better communicates what tends to fade away over time. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but writing is what I do, so I’m passionately writing those thousand words anyway.

Megan, you have such an impressive portfolio of translations, most of which are fiction. As Alejandro chose to have many forms of storytelling in this one work–essays, short stories, poems–what was it like to translate something so vast all into one book with a coherent theme?

MM: There’s a way in which everything Alejandro does surprises me—that’s why it’s a joy to translate his work, and why readers keep reading him. But I can also see the through-lines that run throughout his work, his interests in family relationships and memory and masculinity; he’s been writing about fatherhood since long before he was a father. I don’t know that my approach changes very much in different genres, though I do think different texts ask different things of you. Alejandro’s work in general tends to ask for both meticulousness and creativity, a focus on each individual word as well as on the voice or music of the text. In this book I found myself interrogating certain words and exploring their branching resonances in both Spanish and English, words like “teenager,” childhood”, “childish”, “father”, “son/child”, “parent.” It’s amazing how these words that we think we understand start to shift under a more focused and sustained gaze, and that’s something that happens to me every time I translate an Alejandro Zambra text, no matter what the genre.

How has the process of translating Alejandro over the years changed how you work together? Does the process of translating him differ from working with other authors you regularly translate like Mariana Enriquez?

I really like for the translating process to be collaborative, and I’ve learned that by working with Alejandro. After all these years he’s a great friend of mine, and someone whose voice and presence I depend on in my life. It’s by working with Alejandro that I’ve learned there isn’t really a “right” or “wrong” translation—or if there is, it’s not really the most interesting thing to think about—but that everything in a text can be questioned. Asking questions when I translate is pretty important to me, I always feel like I can understand more or more deeply, and the ability to have those conversations with my writers feels crucial. That’s why I like to keep working with writers, because I feel like that trust is built up over time, and that the project of making their books in English is a shared one, and one that we both care about enormously.

In general, to be a translator, you have to maintain a deep curiosity. Writers do too, of course, but in a slightly different way, because translators have to cultivate an externally directed curiosity, one that specifically seeks out the unfamiliar, maybe, rather than exploring the familiar or finding ways to make the unfamiliar familiar.

In the opening essay that traces the birth of Zambra’s son from day 0 to 365, he chides the expression ‘children’s literature,’ as condescending and offensive, stating that all literature is childish. Did translating this book awaken a childish side in you? Is there a childish quality to the art of translation?

Absolutely, I think the childish side of literature, and of translation specifically, is something that I cherish and cultivate. Learning a new language as an adult is a little like reverting to childhood: you’re learning the names for things, which means you’re shaping a system of interpreting the world all over again. I remember when I first moved to Chile, my friends would specifically compare my language learning to growing up— at first I spoke like a baby, I only knew how to say a few words, then I could make very simple sentences. Occasionally my friends would “award” me years, saying “Megan, you’re more like a 5-year old now,” “Now you’re 7,” or “Oh, you’ve graduated to 6th grade by now,” and it was a joke but that’s really how it feels. I’d say now I’m in my early 20s in Spanish: I think I have it all figured out, but really I’m still learning a lot in terms of cultural references and politics and nuance.

In general, to be a translator, you have to maintain a deep curiosity. Writers do too, of course, but in a slightly different way, because translators have to cultivate an externally directed curiosity, one that specifically seeks out the unfamiliar, maybe, rather than exploring the familiar or finding ways to make the unfamiliar familiar.

How important was translating something so universal yet unique and culturally rooted and nuanced like fatherhood with care to a global audience? Are there any special measures you took to accommodate the specificity of Zambra’s experience, especially having to tie in his growing relationship with his son and his long, sometimes tumultuous, relationship with his father?

Fatherhood is a universal subject and Alejandro’s take on it is specific and personal, so in some ways I didn’t have to think much about the shift to a global audience. But I reread that sentence and I know it’s a lie, because there’s a part of me that’s always thinking about that shift, even when it’s unconscious. And I did have to learn some language about things that are outside my wheelhouse, like soccer and fly-fishing, in order to tell these stories of fatherhood in a way that could have that universal impact. One of my favorite pieces in the book is the one on “Soccer Sadness,” but it’s also one I had to work the hardest on. I don’t know anything about football/ soccer, I don’t even know how to talk about it in English, and that’s one language people are very particular about (our editor at Fitzcarraldo is very helpful here, but I also know there are differences between British and US soccer speak). I also haven’t assimilated the history of teams and players in Chile, and I had to do a deep dive into Colo-Colo and Claudio Borghi and what the hell a panenka is in order to convey the fundamental context of the piece, which is about how, growing up under a dictatorship in a culture of repression, little boys only saw their fathers express despair when when their soccer team lost. What does that teach them, the essay asks, about how and when to express their own emotions? Certainly the displacement of emotion into the realm of sports is applicable elsewhere, but I hope people get a sense from the essay of the particular situation of silence (dictatorship) and scream (cheers, boos) that pertained in Chile.

In the final essay, ‘Late Lessons in Fly-fishing,’ Zambra writes, “The experience of fishing functioned in a decidedly similar way to literature. For those couple of days, our languages coexisted. What I mean is: we coexisted, it worked.” (page 196) As a translator, how did you tap into the language Zambra used to coexist with his son? Were there any challenges involved in carrying this private, ever-evolving language between a parent and a child from Spanish to English?

Alejandro lives in Mexico, and his son Silvestre mostly speaks Mexican Spanish like his mom; he uses Chilean words when he wants to please his dad, like it’s part of their own private language (they also make up their own words, they’re constantly playing with languages and accents). The question of how to convey the different Chilean and Mexican words is pretty recurrent in Alejandro’s work these days, and it doesn’t have a consistent answer. Often the humor relies on this difference—the cry of “There’s no comfort!” Is only funny if you know that Confort is the Chilean “genericized trademark” that means toilet paper. Other times leaving the words in Spanish and conveying variety is enough to get across the narrator’s sense of confusion or dislocation, as when he uses all the words (Bottle mamila mamadera biberón) for “bottle” because he forgets which one is right. And Silvestre uses his dad’s Chilean word for Santa Claus (Viejito Pascuero) when he wants to win him over, which could happen in English, too—in the British edition of the book, it’s the Chilean word for “Father Christmas.”

In general, there’s a sense of playful attention in Alejandro’s use of language that I love to incorporate into the translation. It’s that sense of play and poetry that lets him change the meanings of words, as in a story like “The Kid with No Dad,” in which the childish insults of a pair of 12-year-old boys become tender declarations of affection. That’s the spirit of the approach I try to enact in the translation, as well.

Alejandro Zambra is the author of ten books, most recently Chilean Poet and Multiple Choice. The recipient of numerous literary prizes, as well as a New York Public Library Cullman Center fellowship, he has published fiction and essays in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, The Paris Review, and Harper’s Magazine, among other publications. He lives in Mexico City.

Megan McDowell is the winner of the 2022 National Book Award for Translation and the recipient of a 2020 Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among other awards. She has been nominated four times for the International Booker Prize.