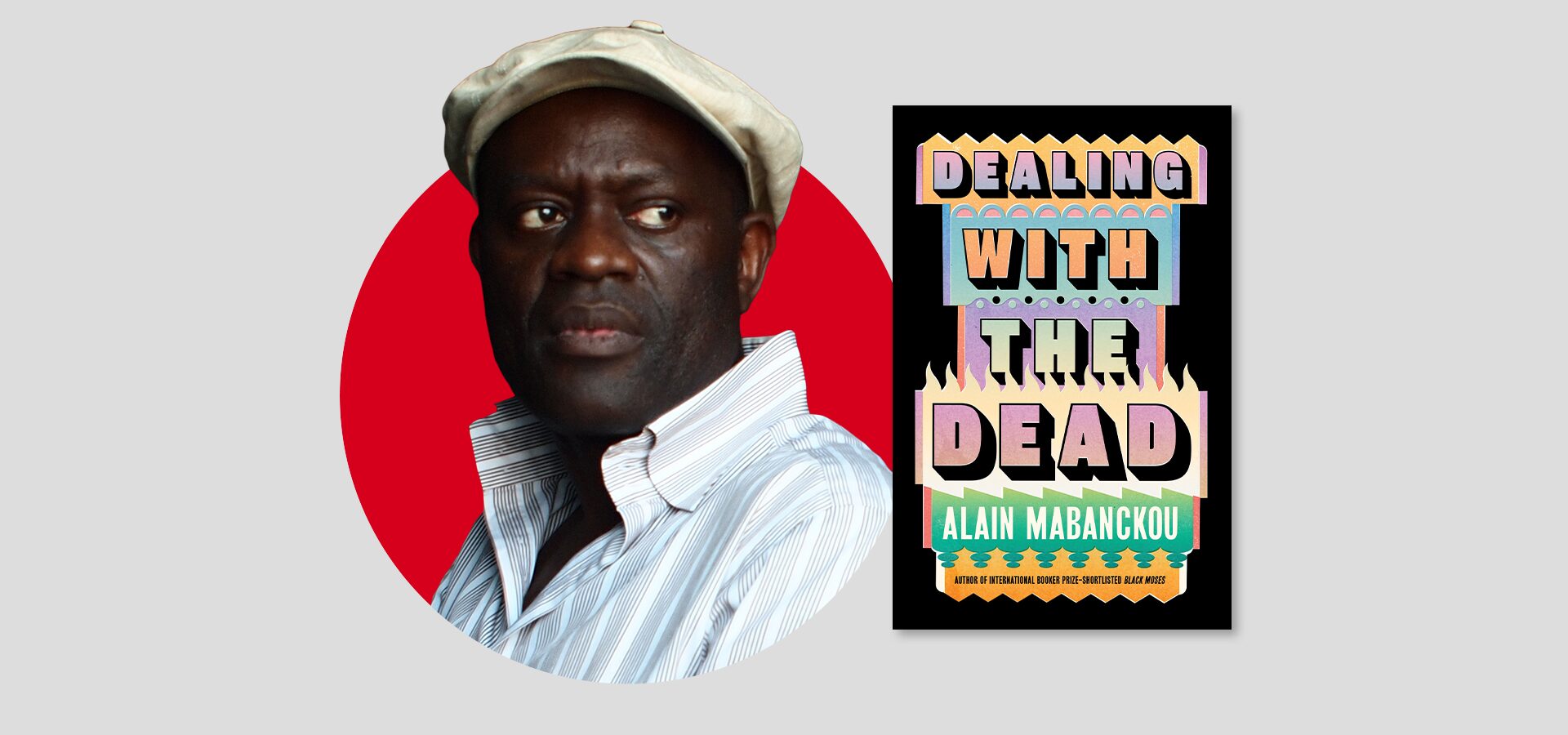

Alain Mabanckou | The PEN Ten Interview

Alain Mabanckou’s Dealing with the Dead (The New Press, 2025 – translated by Helen Stevenson) is a novel about Liwa Ekimakingaï, who wakes in a cemetery wearing flared purple trousers, a red jacket, and green shoes that he will now wear forever. As he tries to piece the story of his death together, Liwa meets the other residents of the cemetery, who share their life stories, filled with regrets and warnings. Instead of heeding their advice, Liwa leaves the cemetery and makes the journey to see his beloved grandmother one last time.

In conversation with PEN America’s Literary Awards Coordinator, Valentine Sargent, Mabanckou shares his relationship with the city of his childhood, the joy that comes with being a writer, and the power of literature in a time when government corruption is a dangerous reality and political violence upends people’s lives. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

I was struck by your decision to write the story from “you” – placing the reader in Liwa’s perspective. Why did you decide on the second person perspective for this story?

I used the second person to tell this story because I was seeking complicity with the reader, a way of making the narrative feel very close to the one who is reading. The second person singular is perhaps one of the most intimate forms of narration, and for me it was almost a way of stepping back and reflecting on my own work.

Political corruption is constant throughout Dealing with the Dead, and is apparent in the Congolese and United States governments. How does your writing navigate truth? What do you believe is the relationship between truth and fiction in times of political unrest?

Yes, corruption runs throughout this book. However, there is also an interplay between truth and fiction during times of political and economic hardship. The book is a fable showing how corruption has already taken hold and continues to eat away at African governments.

The vivid details of Pointe-Noire really stand out, to the point where the port city is a character in itself. In the translator’s note, Helen Stevenson writes that you once spoke of yourself as a migratory bird ‘who remembers the country he’s come from but chooses to stay and sing on the branch where he’s perched.’ Can you share your relationship to your home country and how writing sustains that relationship?

The city of Pointe-Noire is very present in this book because it is the city of my childhood, the city of my adolescence, and the city that has always stayed with me, even though I now live in the United States. My translator, Helen Stevenson, once said that I am a migratory bird, that the country I come from is like a tree on which I once perched. But more and more, I resemble a leaf detached from that tree, carried from continent to continent. She was right.

My novels are always, in some way, a celebration of literature itself.

You reference a variety of characters in the novel such as Tom Sawyer and Quasimodo. Which books did you return to while writing Dealing with the Dead?

As mentioned, American figures like Tom Sawyer and French ones like Quasimodo helped me study how my own characters might behave. My novels are always, in some way, a celebration of literature itself.

I’m curious about your writing process, specifically regarding writing in French and working with your translator, Helen Stevenson. You are a widely recognized Francophone Congolese writer, known to poke and prod at the French language. What literary and linguistic choices are at the forefront of your mind as you write?

I am deeply satisfied with the work I do with my translator, Helen Stevenson. Even though she is European, from the UK—even though she is white and I am Black—what matters is the strength of literature. She has always understood me and has always accompanied me in transmitting thought from one language to another. Our collaboration proves that translation is not a matter of color. Whether you are Black, white, yellow, or red, what matters is the color of literature, and that color may be able to speak to everyone.

In the book there are days-long mourning and rituals where the living assist the dead to the afterlife. How do these rituals counteract the deaths of the characters caused by political violence?

There are many rituals in this book: funeral rites that last for days, rituals where women weep around the body. These rituals are themselves a response to local political violence. They embody the belief that death is not the end of the individual, but rather the liberation of the human spirit.

Our collaboration proves that translation is not a matter of color. Whether you are Black, white, yellow, or red, what matters is the color of literature, and that color may be able to speak to everyone.

What made you want to focus on the dead, specifically victims of political violence, in this novel?

What pushed me to describe death—especially death caused by political violence—was its overwhelming presence. It is always there. And, too many people today disappear because they are victims of political violence.

While political corruption is a consistent theme, I also found community to be a constant thread. Readers can see what happens to characters who chose themselves over others, and those who put others before themselves. What do you want readers to take away from this novel?

Corruption, especially political corruption, is indeed a constant threat. Readers see what happens to my characters, and to others, what is taken away from their existence. I think readers should take away the idea that even when we talk about the most tragic events, there are still other tragedies, even greater, unfolding within the machinery of political violence.

As a novelist who often writes satire, what is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I don’t believe I have any restraints or taboos in what I write. I write what comes to me, regardless of how governments may receive it, regardless of how people may judge my prose. In Africa, writers are always considered dangerous people. That, too, is part of the joy of being a writer: risking one’s life for art, and perhaps saving the lives of others in the process.

In Africa, writers are always considered dangerous people. That, too, is part of the joy of being a writer: risking one’s life for art, and perhaps saving the lives of others in the process.

Language is an incredible tool and asset to all individuals. When did you learn that language had power and what did you gain from that experience?

Language is everywhere in this book—the language of individuals, the language of power, the language of domination, even the language of despair. This book, in its own way, tries to restore courage to those who have lost it. Even in death, the struggle continues. That is the meaning of this book—but also laughter, irony, the pleasure of reading, and the journey through literature.

Alain Mabanckou was born in Congo in 1966. An award-winning novelist, poet, and essayist, Mabanckou currently lives in Los Angeles, where he teaches literature at UCLA. He is the author of African Psycho, Broken Glass, Black Bazaar, and Tomorrow I’ll Be Twenty, as well as The Lights of Pointe-Noire, Black Moses, and The Death of Comrade President (The New Press).