What began in 2023 as a group of just 10 Rhode Island Library Association members concerned about nationwide book bans blossomed into a coalition of more than 300 impassioned community members, whose collective advocacy culminated in the passage of the nation’s strongest Freedom to Read Act last month.

“This was not librarians against the world,” said Nicole Dyszlewski, a member of the Rhode Island Freedom to Read Coalition. “I think that was the key to success, that this wasn’t reduced to a librarian issue or a teacher issue or a parent issue. It was an everybody issue. It was a democracy issue. It was a diversity issue, and I mean that in the best way possible.”

The new law is the first in the nation to provide a private right of action against censorship to librarians, authors, public library patrons, students, and parents and guardians, allowing them to seek relief in court.

The legislation also mandates the creation of policies to limit censorship in public and school libraries. Per the legislation, the policies will restrict who can submit reconsideration requests: Only residents of the municipality where a public library is located can object to its materials, and only teachers in the same district as a school, parents or guardians of students enrolled in a school, or students enrolled in a school can object to content in the school’s library. “That was a big deal, because so many of these attempts [to ban books] are coming from national groups,” explained Cheryl Space, a member of the Rhode Island Freedom to Read Coalition and the co-chair of the Rhode Island Library Association’s Legislative Action Committee.

The policies will also establish committees to evaluate reconsideration requests, which cannot be approved based on “the origin, background, or views of the library material or those contributing to its creation.” The addition of the second clause serves to protect authors and illustrators, many of whom are targeted solely on the basis of their race or sexual orientation, said author Padma Venkatraman, a member of Rhode Island Authors Against Book Bans and the Rhode Island Freedom to Read Coalition.

The legislation also states that individuals who object to content must “review the material as a whole” and that “[s]elective passages from the material taken out of context shall not be considered” by the review committees. And while material is under review, it cannot be removed from the library — a provision that ensures students do not abruptly lose access to large swaths of literature.

A Coalition Begins

Hardly any explicit book-banning efforts have taken place in Rhode Island. According to Space, the most well-known case of an attempted book ban occurred at Westerly High School, where Maia Kabobe’s Gender Queer was unsuccessfully challenged. The memoir, which topped PEN America’s list of the most banned books during the 2021-2022 school year, seeks to offer its readers language that can help them describe their gender identity. Of the more than 16,000 instances of book bans PEN America has documented since 2021, just one — a ban on Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home — occurred in the state.

But in 2022, a few members of the Rhode Island Library Association attended a seminar at the New England Library Association Conference, where they learned about book-banning efforts in other states. They also learned that Rhode Island was the only New England state that did not already have protections for library workers and educators embedded in obscenity law, Space said. Obscenity laws have been weaponized across the country to threaten library and education staff with criminal charges.

In 2023, a small cohort of the Rhode Island Library Association members and other activists proposed a piece of legislation that would protect employees of schools, museums, or libraries facing obscenity charges related to literary and artistic works.

The bill died in committee, and efforts to pass a similar piece of legislation were unsuccessful the next year. The group also tried in vain to pass a complementary bill that sought to prohibit the practice of “banning, removing, censoring or otherwise restricting access to specific books or resources due to partisan or doctrinal disapproval” in public libraries.

“I’m going to be honest, I’m actually glad [they] died last year, because we have a much better bill this year,” Space said. “It’s just such a thrill that it’s here, and it’s really a win for everyone in Rhode Island.”

Two members of Rhode Island Authors Against Book Bans — Venkatraman and Jeanette Bradley — provided testimony for the prior bill protecting library workers and educators, but they believed it would be stronger if it included protections for Rhode Island authors and illustrators. Directly following the presidential election, which the pair said gave a new sense of urgency to their work, they joined forces and reached out to dozens of groups to form the Rhode Island Freedom to Read Coalition.

By the time the coalition had shepherded the passage of the bill, it included more than 20 organizations, including the Rhode Island Council of Churches, the Rhode Island Jewish Alliance, the New England Independent Booksellers Association, the Rhode Island League of Women Voters, EveryLibrary, PEN America, and the youth groups Young Voices and the Alliance of Rhode Island Southeast Asians for Education.

Model Legislation

In drafting the legislation, coalition members contacted legal experts at Penguin Random House and Rhode Island ACLU to assist with the writing of the bill. They modeled the bill on New Jersey’s Freedom to Read Act, which Governor Phil Murphy signed into law in December 2024. Among other strengths, New Jersey’s bill clearly outlined the elements of a collection development policy for both public and school libraries, according to Space.

Now, Rhode Island’s law can serve as a model for other states. “The law’s robust protections for librarians, writers, and readers set an exemplary model that we hope to see other states replicate,” said Laura Benitez, state policy manager at PEN America. “As the Trump administration and book-banning groups continue their attacks on libraries and free speech, we urge legislators nationwide to make their states safe havens for the freedom to read. You can never be too prepared to stop book bans.”

Finding Like-Minded Allies

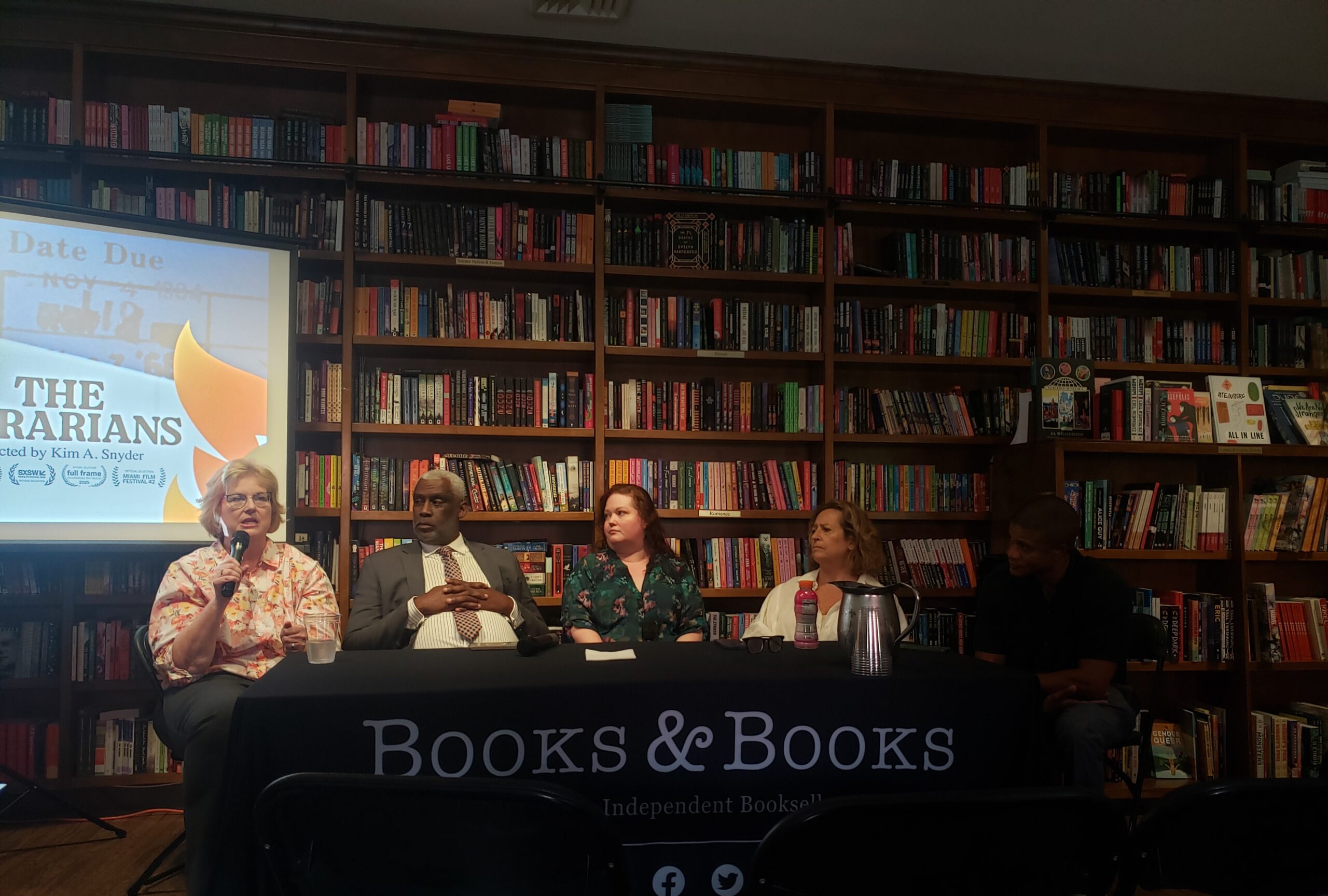

In order to garner support for the bill, the Rhode Island Freedom to Read Coalition held a number of events across the state. They hosted a series of discussion panels, which typically featured four speakers: an author or illustrator, a librarian, an educator or representative of a school committee, and a fourth supporter who could offer a different perspective on the bill, such as a faith leader or member of the Rhode Island ACLU.

“I was always so impressed by how many people showed up and how engaged the folks who came to these panels were,” Bradley said. “They were fired up and wanted to make a difference.”

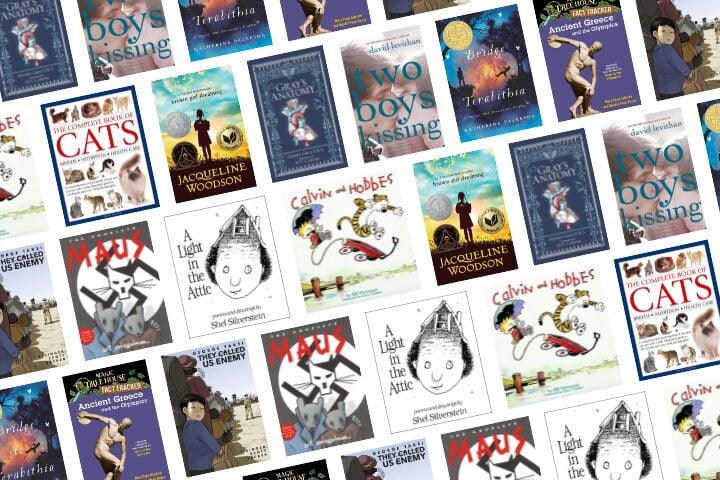

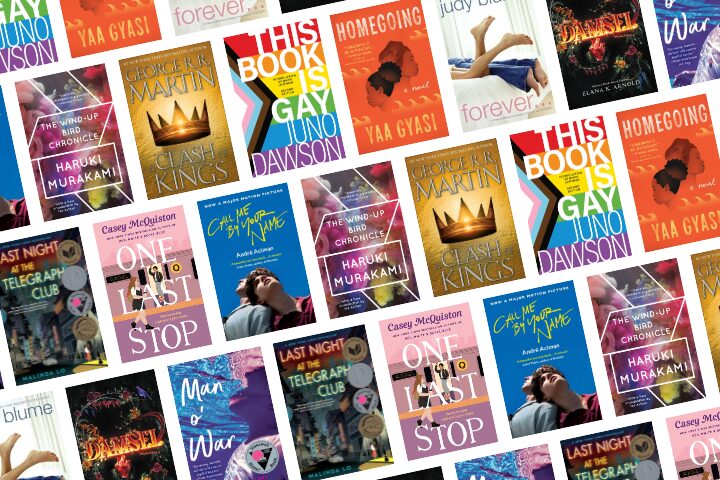

The group also held statewide “postcard parties,” where they distributed postcards created by local illustrators, many of which featured banned books by Rhode Island authors and anti-censorship slogans that played off of the titles of the books. Following a loose template provided by the coalition, attendees wrote about why the freedom to read mattered to them and urged their legislators to pass the bill. Libraries across the state also handed out postcards to patrons.

“We tried to meet people where they were at, and where they were at was all over the state, at a variety of different places, including libraries [and] churches,” Dyszlewski said. “And we got largely a positive response from the citizenry of Rhode Island — not just positive, but passionately positive.”

The coalition also hosted an “artivism” event at the Rhode Island State House, where they displayed banned books by Rhode Island creators. The event served to raise awareness about the kinds of literature commonly targeted as well as the ways in which that literature is targeted, Venkatraman said.

Bringing the Effort Home

In her efforts to protect literature throughout the state, Venkatraman took inspiration from a character in another one of her novels, Born Behind Bars, who declares, “Fear is a lock, courage is a key.” “I thought about that a lot. I thought, ‘I can’t just write books in which kids are heroes. I need to take action myself,’” Venkatraman said. “I felt very much like I needed to live the words that I was writing.”

Space said that opponents of the bill, who rarely interacted with the coalition but who provided testimony at its hearings, argued that it represented an attempt to push a “woke agenda” onto students and interfered with parents’ rights. “We just kept trying to reiterate that you still have every right to control what your child is accessing,” she said. “If you’re a vegetarian or a vegan and you go to the grocery store, you don’t demand that everything else be taken off the shelf. You choose what’s right for your family. It’s really the same thing in a public library.”

She added that advocates for similar legislation in other states should know that the coalition’s success rested on its size and diversity. “There are so many bills that are introduced, and there has to be a tidal wave of momentum to actually get the bill to the floor for a vote,” she said. “Building that very broad coalition is the best advice we can possibly give.”