Learning Together: How One Family Is Navigating Life in Florida

October 23, 2023

Abigail Walker was excited to pursue an opportunity as a full-time music teacher at a Christian private school in Florida. As a musician with more than a dozen years’ experience teaching music at colleges, she knew her résumé and background made her a top candidate for the role.

She’d already completed the paperwork—and was about to be called into her interview.

But she had just one last box to check on her application.

At another stage of her life, Abigail might have viewed checking this box as simply a formality. But today, it stood as a massive obstacle in her way. Her prospective employer was asking her to check a box saying she shared the Christian’s school’s religious opposition to both divorce and homosexuality.

She thought of her good friends, gay friends, who had come out to their Christian families and were kicked out of their homes, shamed, and even told that their hearts, in the sight of God, were already turning cold.

Reminded of the “black heart” demerits from her sister’s childhood, “I was devastated that their faith, a faith that I still held at that time, had driven such a wedge into our family and knew it was boxes like this that had done it.”

She left the box unchecked and headed into the interview.

“They asked me what I would teach and then spent 40 minutes telling me how I needed to rethink my understanding of God and homosexuality,” she told me recently.

To Abigail, the incident was about more than not getting a job.

“I freaked out,” she said. For a while, she even contemplated uprooting her family.

Abigail Walker and her family.

But Abigail, her husband and their three sons stayed in Pensacola, Florida. Abigail found another job soon after. She now teaches music at a local secular school.

I met the Walker family in Florida in the summer of 2023 when I was making videos for PEN America ahead of this year’s Banned Books Week. It just so happened that Abigail’s optometrist is Lindsay Durtschi, one of the parents involved in PEN America’s current lawsuit over banned books against Escambia County. When Abigail went to pick up some eyeglasses, Durtschi (whom I had already interviewed) asked her if she knew any kids who might be interested in participating in a video interview.

Abigail immediately saw this as an opportunity for her family, “to speak for what we believe and not into a vacuum. This is important for our children to see that their voice matters—and that someone is going to listen to what they think and what they say.”

Abigail asked her three sons—Winston, Liam and Jules—and her oldest, 13-year-old Winston didn’t hesitate to volunteer.

PEN America’s Damarcus Adisa with Winston.

When I showed up at the family home, I didn’t plan on spending several hours with the Walker family—or on being invited for dinner, or seeing their backyard farm, or staying up chatting till close to midnight.

In addition to interviewing Winston, I learned that Abigail and her husband both had a Christian home school upbringing. She met her husband at age ten and they started junior college together at 14. But along the way they decided they wanted to give their own kids a different kind of upbringing and education than the one they had experienced.

After the visit, I invited Abigail to a Zoom call to learn more about her history, how her own thinking has evolved along the way, and what she tries to teach—and learn from—her kids as they navigate life in Pensacola, Florida today.

She told me that her mom began homeschooling her and her siblings in the late ‘80s after her elder sister, attending a private Christian school, was given a “black heart” demerit that both the child and Abigail’s mother found upsetting. Her mom—a historian—did more than just teach academics. She also started a homeschool band and got involved in politics to allow homeschoolers to participate in extracurricular school activities.

“There was just this feeling from our family that politics and getting involved in what is happening on a legislative level is something that can make a difference, that it’s important that you speak out for what you believe in.”

In junior college, Abigail began getting exposed to literature “that had rape and murder and nudity and profanity and all these things that are being banned from our schools today. I asked my professor, ‘can I read something else?’ And he said, ‘if you want to go live in your glass house you can go back to Pensacola Christian College where you came from.’” Unsure how to respond, Abigail dropped the class.

At the time, Abigail felt compelled to challenge the stigma against Christian homeschoolers. “Homeschool Christians are taught to debate, but not the facts,” she said with a laugh. ““So we end up debating around the facts or sometimes in spite of the facts just to prove our premeditated moral point.”

She went on to study music at Florida State and earn a Master of Music at Rice University, where, “I was around quite a few people who spoke pretty verbally about how I didn’t know what I was talking about.”

After marrying her husband, who by now had an engineering degree, the couple began discussing their roles within the marriage. Abigail rebelled against the idea of staying at home. “There was no me that was ever good at keeping house or taking care of babies. That was never on my mind.”

“I could not honestly agree with what the people around me were saying, based on what I saw.“

Abigail gave birth to three kids, and has continued to perform with orchestras and teach music at schools and colleges in the Pensacola area.

Abigail is learning from Winston, too.

In recent years, Abigail sought to stay true to her faith while realizing, “I could not honestly agree with what the people around me were saying, based on what I saw.”

She is now trying to learn more about Black history through listening to Black voices. “Students need to learn where to find knowledge and how to recognize fact from fiction. They need to learn to use their voice to tell their story, not to erase the stories of others.” She wants to give her students and children more resources, more facts than she was given.

She has also allowed herself to be educated by her own kids who “easily empathize with people I was taught to look at in a more segregated way. My kids and students have been critical in waking me up from my entitled dreams of what America is supposed to be for the white Christian moderate and accept it as it is.”

“Winston never met a person that he could make sense of pushing away,” she told me. “That’s just who he is.”

“Winston never met a person that he could make sense of pushing away. That’s just who he is.”

As for my interviewing Winston, “I didn’t know what to expect,” said Abigail. “I didn’t know what Winston was going to say. I just told him, ‘Just say what answers you have.’”

Winston’s a 13-year-old with his own strongly held opinions, and the ability to think for himself as is evident in the video interview I did with him.

If “woke” means being open-minded and willing to listen to a version of history that counters a heroic white nationalist narrative, Winston is down with that. His attitude is that wrongs should be corrected, not denied—and that it’s more important to do what’s right than live in a bubble.

Gov. Ron DeSantis may think that Florida is “where woke goes to die,” but based on what I saw on my recent trip, that message hasn’t gotten through to kids like Winston—or moms like Abigail Walker—just yet.

Damarcus Adisa is PEN America’s video producer.

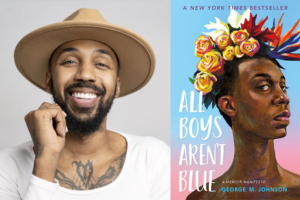

Banned in the USA Spotlight: George M. Johnson

Pride Month: A Banned Book Reading List