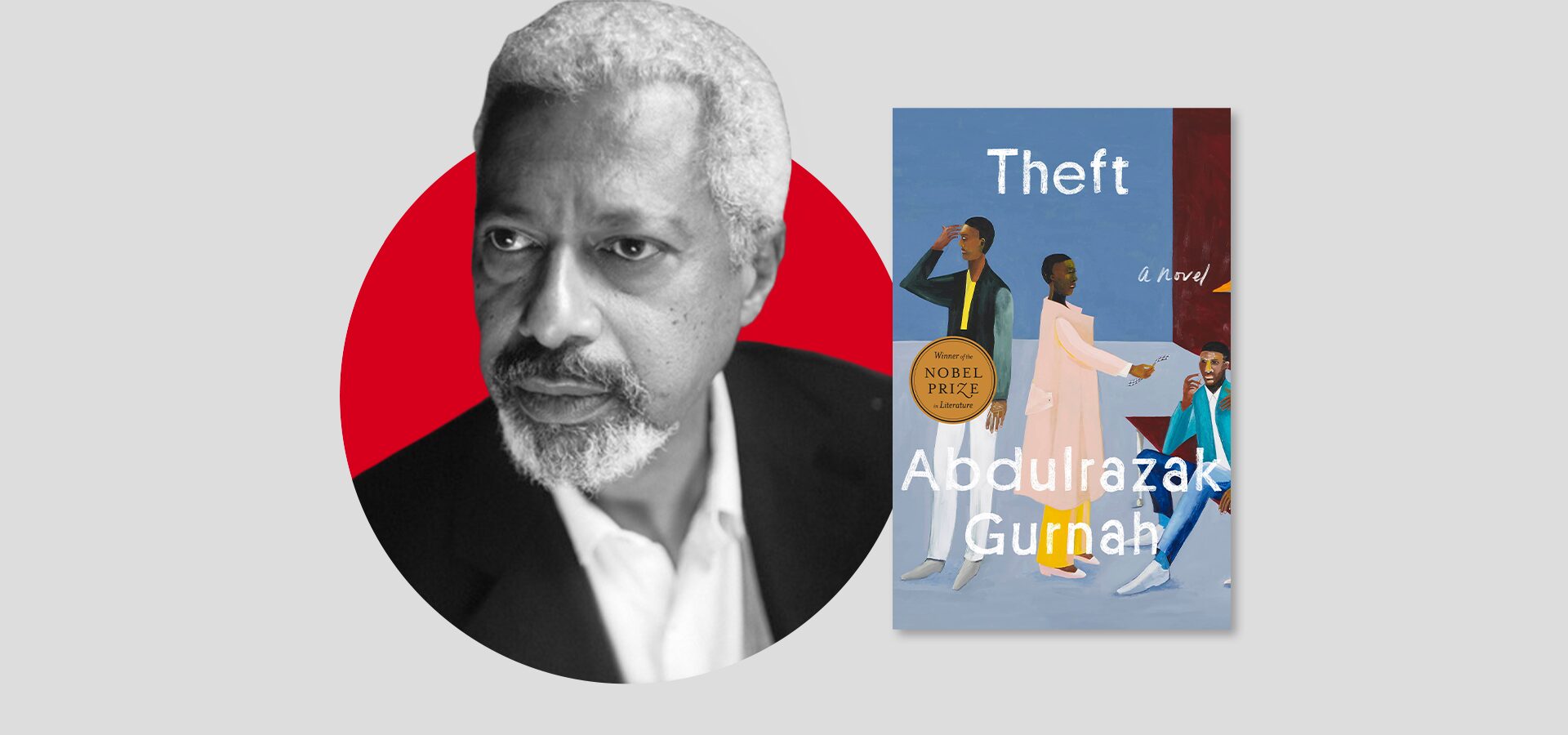

Abdulrazak Gurnah | The PEN Ten

In Theft (Penguin Random House, 2025), his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize in 2021, Abdulrazak Gurnah follows the interwoven stories of three young adults navigating questions of identity, destiny, and coming-of-age amid the globalizing landscape of turn-of-the-century Zanzibar. As their lives are rocked by the transformational tides of technology, tourism, and geopolitics, Karim, Badar, and Fauzia search for meaning and purpose, uncovering the intricate truths of their family histories in the process.

In a conversation with PEN America’s Research Program Manager Hanna Khosravi for this week’s PEN Ten, Abdulrazak Gurnah speaks about the experience that inspired the novel’s title, and explains why reading is a “complicated pleasure.” (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

This is a novel rich with intertextual references. The books that your characters are reading not only inform us of their tastes and interests but also portend key dynamic tensions. Why is it important for you that your characters are reading, and that you document what, when, and how they are reading?

Reading is a complicated pleasure. We read for different reasons, to understand, out of curiosity, to be diverted, to be entertained, and sometimes all of these pleasures are bestowed on us at more or less the same time. For some of the people in this novel, the more instrumental dimension of reading is more important, for others reading is very nearly a vocation, or a way to self-retrieval or self-knowledge.

The concept of “theft” is a propulsive through-line in this book – almost every character’s life is defined by that which is stolen from them by someone that they once trusted, and by their knowing or unknowing relationship to the deception. Of course, “theft” plays a role in much of your work, which often chronicles the theft upon which structures of colonialism are contingent – the theft of land, the theft of history, the theft of time. How did you settle on the “theft” as the central, titular tenet of this particular novel?

It began with an unjust accusation of theft which occurred many years ago. I knew someone who was employed as a servant in a neighbour’s house. I was a schoolboy, and of course he was not, but we were the same age and we shared many friendly moments. He was a servant, poor and powerless, and forced to skivvy for his betters. It was not an uncommon phenomenon. He swept and cleaned, went to the market for the mistress of the house, ran errands to the grocery store where the household had an account. He was accused of stealing a pound of sugar or a packet of biscuits or something paltry like that, and he was shamed and dismissed. Even then, it seemed such a powerful demonstration of his powerlessness. The injustice of that stayed with me, as a distant, peripheral memory. Then at some point it bubbled to the surface and needed to be written about.

In A Small Place, Jamaica Kincaid writes that “a tourist is an ugly human being.” In Theft, one of your protagonists, Badar, spends a large part of the novel working in a hotel in turn-of-the-century Zanzibar. The relationships he forms with two humanitarian workers staying at the hotel lead the characters to debate the difference between the position of the “tourist” and the “aid worker.” Why did you choose to place tourism, aid work, and the space of the hotel as a primary nodal point of Theft?

The hotel is itself a symbol of theft, of dispossession. The original owners of the building have long since been forced to leave. There are many such ‘boutique hotels’ in Zanzibar, some cheaply acquired by friends of the government. Hotel, in this context, means there will be tourists, whose presence is often ambiguous. They bring livelihood but also corruption, often unintentionally. My interest in the ‘aid’ volunteers here is not intended to typify the whole enterprise, but the particular disturbance which results on this occasion.

Reading is a complicated pleasure. We read for different reasons, to understand, out of curiosity, to be diverted, to be entertained, and sometimes all of these pleasures are bestowed on us at more or less the same time.

You have been lauded for capturing the “gulf between continents and cultures” in your novels. Unlike many of your most famous works, this book takes place entirely within Tanzania. The character of Badar, however, believes that he is actually able to travel through maps and images on his computer screen, even going so far as to memorize spatial characteristics of London’s urban life. Why did you choose to utilize technology in order to visualize space, travel, and migration, rather than actualize it as you have in your other novels?

It seemed better to let him stay home and travel the world through words and images, primarily to demonstrate the freedom that this technology had brought to so many who were cut off from the larger world of knowledge and spectacle. He does not just visit the London streets, he also travels to Hafez’s tomb in Shiraz.

Theft is brimming with dialogic vacuums – with words, stories, and histories left buried and unsaid. In your Nobel lecture, you described your sense of national history and your experience with exile, writing that “Our histories were partial, silent about many cruelties.” Why does silence, and the space that it occupies between generations, matter so much to you in your work?

The lacunae left undescribed are already familiar to most of us. Leaving them hinted at but unelaborated upon enhances their impact at times. It may also be that to provide too much detail is to risk simplification. In any case, there are many situations when silence speaks volumes, and it is a useful defence for the powerless.

One of the most rewarding parts of reading Theft is the gradual recognition of which seemingly tangential characters or generational details are actually essential to the story’s arc. However, you keep the POV firmly set between three characters of a similar age range, all of whom grow from their teens to mid-20s throughout the course of the book. Why did you choose to exclude the elder characters in this book from its POV? Why did you remain fixed on Karim, Badar, and Fauzia, and what does their particular generation represent to you?

In some respect, theirs is the transitional generation. They were not around during the last years of European colonialism and did not participate in the exhilarations of the decolonising campaigns. So perhaps they do not share the sense of resignation that followed the crushing of post-independence hopes. As they grow older, opportunities open up that would not have been there in their childhood, as do new temptations.

There are many situations when silence speaks volumes, and it is a useful defence for the powerless.

The epigraph of your book is a line from Joseph Conrad’s Chance – “In a general way it is very difficult for one to become remarkable.” Any reference to Conrad in a novel about postcolonial life is laden with meaning – of course, there have been vast movements of intellectual thought formed around criticisms and contestations of Conrad’s work, one of the most notable examples being Chinua Achebe’s lecture, “An Image of Africa.” Was Conrad’s writing a part of your thinking as you were forming this novel? Were there particular novelists who influenced you as you were approaching Theft?

No, Conrad was not part of my thinking when I was writing this novel, although I am reader of his works and I have taught several of his novels and stories over the years. His texts have been subject to much blunt criticism over the years, some of it justified, but the problems so identified are not all there is to his writings. I was re-reading Chance after I had finished writing Theft, and I thought the understated wit of this line suited Badar’s progress in the novel.

Throughout the last few years, I have often returned to a passage in your 2017 novel Gravel Heart, in which Salim, who had left Zanzibar for England in his adolescence, describes a sense of content, albeit melancholic resignation to his fate as he prepares to buy a flat in London – “I am still here after such a long time when I never thought to be here long when I first came. Everyone says that: I didn’t think I would stay for long…It just seems as if every day happens like this, coming and going with nothing to report at the end of it.” As a child of diaspora myself, I was struck by Salim’s passive acceptance, by his belief that we can grapple relentlessly with desires to control and prognosticate, but much of our life is composed by that which we simply fall into. Theft, on the other hand, treats fate differently – it speaks so directly about volition, about taking life into one’s own hands. Throughout your oeuvre, we can clearly perceive your characters actively contending with their relationships to fate. What role does the conceptualization of “fate” play in your writing process?

I would say circumstances rather than fate. The latter makes it seem as if a narrative of our lives is already constructed and waiting to work itself out. Salim in Gravel Heart stumbles from one episode of his life to another, partly because he is a stranger where he finds himself and therefore unavoidably adrift to some extent, and partly because he had somehow lost hold of his moorings a long time ago, as a result of decisions made by others. In Theft, one person speaks in such grandiloquent terms as ‘taking life into one’s own hands’. Others learn to endure.

When you won your Nobel Prize in 2021, there was a great deal of chatter surrounding the circulation of your novels and the fact that your books were difficult to find in U.S. bookstores. Since then, of course, everything has changed. Afterlives, your last novel, was a bestseller around the globe. How does it feel to have such increased attention around this release, and did you consider that potential new readership or spotlight when you were writing?

It is, of course, quite wonderful to have all the novels back in print and finding readers in so many places and so many languages. What writer would not be delighted by such an outcome. No, I did not consider the potential new readership for Afterlives as a result of the Nobel award. It was published in the UK in 2020, about a year beforehand. It came out in the US afterwards.

I would say circumstances rather than fate. The latter makes it seem as if a narrative of our lives is already constructed and waiting to work itself out.

In many ways, this is a story that revolves around power – the sources from which individuals derive power, and the colonial structures and institutions that codify power and its flagrant abuse. What do you hope that readers can take away from this exploration of power on a personal scale and on a communal scale?

I hope they will find pleasure in reading it. That is what I hope with what I write, and what I hope for when I read. As I said in answer to the opening question, such pleasure is complicated.

Abdulrazak Gurnah is the 2021 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. He is the author of ten previous novels, including Afterlives (named a 2022 Best Book of the Year by the New York Times, Washington Post, TIME, and The New Yorker), Paradise (shortlisted for the Booker Prize), By the Sea (longlisted for the Booker Prize and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize), and Desertion. Born and raised in Zanzibar, he is Professor Emeritus of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent. He lives in Canterbury, England.