This Q&A is part of a series of interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

Political polarization, extremism and social media algorithms have contributed to a rise in partisan misinformation in the United States.

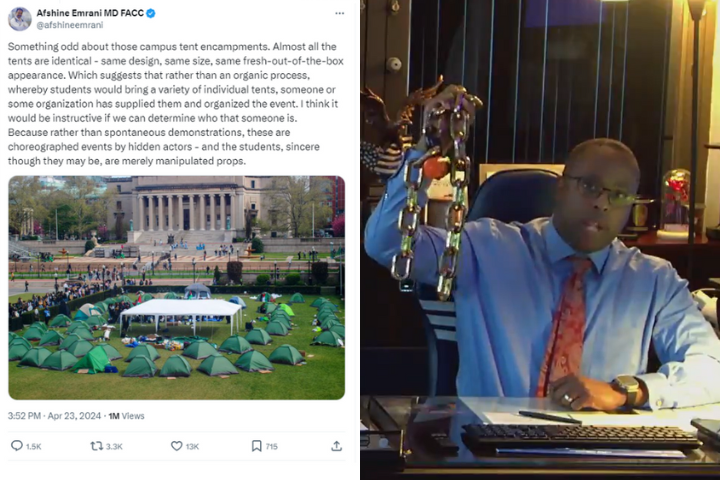

Right-leaning media can be a hotbed of conspiracy theories, from racist claims questioning former president Barack Obama’s citizenship more than a decade ago to the misinformation narrative about immigrant communities eating pets. On the left, the July assassination attempt on former president Donald Trump generated conspiracy theories, with the most popular claiming the incident was staged to boost Trump’s chances in the presidential election.

We talked to Columbia Journalism Review’s Mathew Ingram about a rise in misinformation and the underlying beliefs fueling partisan falsehoods.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

You recently wrote about the rise of left-wing misinformation after the first assassination attempt on Donald Trump. What do you think is the biggest difference between conspiracy theories that originate on the political right and conspiracy theories that originate on the political left?

I don’t think there is that much of a difference, to be honest, apart from the topics that the disinformation tends to be about — primarily race-related, such as immigration for the right. The impetus to believe or redistribute the disinformation is the same, however: the desire to see something that isn’t there because it confirms one’s prior beliefs about a person or an event.

Do you have any advice for journalists covering political misinformation coming from the left? Should the approach differ from when they cover right-wing misinformation, or are the fundamentals the same?

I think the fundamentals are the same. If a piece of information sounds a little too good to be true — meaning, it fits your preconceptions or beliefs a little too well — then you should question it even harder than you would otherwise. And also if it triggers a powerful emotion of some kind, which means it is hitting its psychological target.

What do you think tends to make a conspiracy theory or misinformation narrative more salient on the left vs. the right?

I don’t think there is anything that differentiates the two except the underlying beliefs that the misinformation is targeting: certain races and/or immigration are bad on the right, vs. Trump and his followers are fascists who want to create a “Handmaid’s Tale”-style dictatorship, etc., on the left.

I’m not sure if you watched the debate between Trump and Harris — if you did, do you think the moderators did a good job of fact-checking both candidates? Do you think fact-checking after the fact is enough when false information and ideas can spread so rapidly?

I think the moderators did as well as anyone has in that position. It’s difficult to fact-check without interrupting the flow of the event too much, but I think they fact-checked enough to make it clear just how much Trump was stretching the truth. As for whether fact-checking works at all, that is an ongoing debate! If it does help, it likely only does so for a small percentage of the audience. Many who believe the fact being checked are unlikely to change their minds — in some cases, the fact check might make them more convinced that they are right.

Left-wing misinformation isn’t new, but it’s historically less potent and common than right-wing misinformation. Why do you think left-wing misinformation has taken off so much this election cycle?

I think misinformation in general has increased, or at least the redistribution of it has — in part because of the way algorithms on platforms like Twitter (X) function now. And I also think that this election cycle, the candidates and their platforms are far more polarized than they have been in the past, which I think tends to push people in the direction of misinformation.

How do journalists cover left-wing conspiracy theories and falsehoods without creating a sense of false equivalence with right-wing disinformation?

I think they need to be fair, but also cover misinformation proportionately — not everything is equal. A rumor that Haitians are eating cats and dogs is not the same as a rumor that Donald Trump is deliberately mispronouncing Kamala Harris’s name. If journalists do this and it creates the impression of false equivalence, then that is something they will have to live with.

How do you think political journalists can gain readers’ trust amid this intense polarization?

The same way they always do: by being fair and accurate, and putting things in context.

Mathew Ingram is an award-winning journalist who has spent the past two decades writing about business, technology and digital media, as well as advising media companies on digital strategy. Most recently, he was the chief digital writer for the Columbia Journalism Review, and before that a senior writer at Fortune magazine, where he wrote about the evolution of media and the internet. Before Fortune, he held a similar position at Gigaom, a technology blog network. Ingram also spent 15 years as a reporter and columnist at the Globe and Mail in Toronto.