Elisabeth Houston | The PEN Ten Interview

November 2, 2023

It’s always exciting to witness how a writer or artist deepens their craft across multiple works, but it’s even more interesting to see how one character is developed across genre and medium. In Standard American English, Elisabeth Houston writes poems that center a character, baby, she’s been working with for many years in her performance art. In this book, she engages the fetishization of Blackness, mental illness, body image, sexual abuse, and other forms of power struggle. Infusing surrealism and satire, Houston’s work requires readers to move beyond the realms of the conventional. The questions are big, and the page (stage?) is endless.

In this PEN Ten interview with Malcolm Tariq, Senior Editorial Manager for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, Houston discusses her experience developing one character over multiple mediums, how she learned to embrace popular culture in her writing, and how her writing practice varies. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. At the center of Standard American English, is the main character, “baby.” From my understanding, baby is a character you have been developing for years. Despite the name, baby goes through all sorts of changes and transformations that would seemingly make her much older than a child. From her time at school to how she engages with the art world and sexual relationships, I eventually began to read baby’s life here as a coming of age story. Was that how you intended this figure to be read?

That’s an interesting interpretation. Coming of age stories aren’t really a category I’d considered in relationship to the book, but what you suggest doesn’t seem wrong. The term seems to brush against young adult fiction, which the book is decidedly not. YA lit might make cameos in the book, but paradoxically so much of what exists here seems far too grim to really ever be considered “coming of age” in a traditional sense of the word. The work is visceral and psychologically difficult, so I think of its audience as being mature – but I might be wrong about audience and also definitions of genre, also definitions of maturity. It’s not for kids, yet there are so many references to “baby” – but who is baby?

I don’t know. I guess coming of age stories can take so many forms and they can have many audiences. I suppose when I read or encounter film or TV I am just too absorbed in a story to think about its literary frame. It’s a living thing, the work of growth and change. So much of what it means to transform can spark a good story and maybe that is what it means to “come of age.”

2. While we’re on the subject: baby. For the same reasons that I asked the previous question, I’m wondering about the intentionality behind this name. “Baby” can mean an actual baby or it can be a term of endearment. I am also thinking of how women (and people read as women) are catcalled on the street and expected to respond positively to strangers making unprovoked comments on their physical appearance. Why did you choose this name and were there others you considered?

I never considered other names for baby. Baby was always “baby” – who is always baaaaby, who is also always baby! or baby? or baby. I’m interested in the elasticity of the word, what it conjures and what contradictory ways it is read. The nuances of the ways in which I write baby – as baaaby or “baby!!!!” or baby – shape the ways I understand who is speaking in the text and who is writing baby down. Each subtle change in language shapes the ways we understand baby and also who might be authoring baby. Is it the narrator or author – or is it another character inside the text? Is it the reader? Who are the many voices who dictate who baby is and also how she is represented? These are critical questions.

“I think that the strange thing about working with fear is that once you get in the ring, you kind of can’t stop staring it down; it can even become exciting to confront. And addressing fear vaporizes it sometimes.”

3. What role does popular culture play in your work? Standard American English makes references to celebrities such as Gwyneth Paltrow, but also some throwbacks to Lisa Frank (which I loved when I was younger) and cartoon characters Ren and Stimpy. Especially with the latter two, I see them as cultural, time-oriented references, more than an engagement with the contemporary.

What’s funny is how much pop culture was a vernacular I resisted when I began writing; my resistance was ideological, it was kind of pathetic. I am embarrassed as I look back on it. I began with a flimsy idea that poems could only be constructed through simple, elegant metaphors – each poem needed to be stamped with a big white moon, a quiet lake. A pastoral romance hovered over my ideas of poetry and the poems I was writing when I started out; they were never very good. There was one stack of poems with a bright white moon and I believed these were the poems should be served to workshop, so called sophisticated poetry readers. It was bullshit. Then there was another secret stack of poems I constructed furtively, which satirized Gwyneth Paltrow, which detonated pop culture. I didn’t understand the pop culture poems. I believed I was failing. I believed I was failing poetry and also what poems I wanted to write – but poems will assert themselves whether you like them or not. I certainly didn’t want a daytime soap opera to appear in any poem of mine. I was kind of a snob. I had high literary aspirations which I could never meet in my own work. I always felt absurd. I wanted to be serious, but the writing always felt like a joke. Then I started to ask myself about what seriousness meant anyway and why I chased it. At a certain point, I just gave up and allowed the poems to be what they wanted to be. I am constantly failing at the project of capital P poetry. It takes time, I’m still learning.

4. What inspired and motivated you to write this book? Why was it time to write baby into this existence, textually?

I don’t have a simple answer to this question. I suppose I’m driven to put my work out in the world precisely because of the desperate state of the world. I see connections between the work and its obsession with consumerism and technology, power and politics and also the news stories which rapidly reveal our deteriorating and violent world. Rape, revolution, war. Sometimes it feels so intimate, sometimes it feels so alien. None of it is new – but it does feel like the internet has saturated our minds with violence on an unprecedented scale.

I look out at the world and I see it refracted, in jagged pieces, in the book. Yet this is a book I did not want to write. I resisted baby and also writing baby down for a long time. I also witnessed within this resistance an enormous energy and then at some point that energy overtook me and became fuel for the text. There is shame, transgression, violence in this work. There’s also a dark, malevolent comedy. It wasn’t easy to contend with any of this, certainly not as I wrote. I had to overcome tremendous fear, and I think that the strange thing about working with fear is that once you get in the ring, you kind of can’t stop staring it down; it can even become exciting to confront. And addressing fear vaporizes it sometimes.

“I also learn a lot from watching people engage with the work in real time. It’s interesting to see when people cringe, laugh, flush with shame. The expressions on another’s face often mirror my own at some stage of the process.“

5. Poets who have endorsed the book include Khadijah Queen, Tracie Morris, and Pamela Sneed—writers who incorporate performance into their work, while resisting the limits of form. Reading these poems, which I describe as vignettes, I can’t help but feel like I am watching a film or an animated project. Even the words themselves move across the page in ways that require me to read them aloud, or to image them with sound. What is your relationship to performance and sound in poetry?

I’ve been performing for a while now, and I’ve got a tortured relationship to the medium; it has birthed me as an artist, but it has also destroyed me as an artist. It requires so much – body, soul, spirit, language. It can all be chewed up by the machinery of performance. There’s a lot on the line, which is terrifying and exhilarating at once. A performance can also fall apart in flash, you’re really walking a tightrope. Sound is certainly part of it, but I also approach silence carefully and reverently. There is so much alive in silence.

6. I’m curious about how you wrote this book, and what writing looks like for you in general. This feels like something you can’t write sitting down. Can you tell us about your process?

I don’t rely on a particular writing routine, but I try to generate a lot of material. It depends on what stage I am in the writing process; the beginning stages are mostly about generating material. I don’t try to shape the material until later, and I am constantly reshaping the text. I write by hand, but not exclusively. I usually begin writing by hand and I also try to switch up the materials with which I write: I sometimes write on newspapers, post-its, index cards. I like notebooks too. A computer comes into the process in the later stages. I also share writing in performance, so there is sometimes a body moving about a room, passing out pages of text.

I also make videos; the form transformed my writing process and taught me to loosen up. Process can be tedious or it can be fun, and I love engaging with mediums – video, digital media, photography – which force me to consider language in new and surprising ways. I also learn a lot from watching people engage with the work in real time. It’s interesting to see when people cringe, laugh, flush with shame. The expressions on another’s face often mirror my own at some stage of the process.

7. Who and/or what are some of your influences? What writers have you recently enjoyed or studied?

I find myself far more concerned with the practice of creating than I am with whatever may or may not be influencing me; influence can change at any moment and subject is always a moving target, but the rituals of writing will always be demanded of me and I find this to be the more important task. I always need to put pen to paper, whether I am inspired or not. Influence and inspiration are strange and hard to locate.

That said, I love poets and novelists. I also sneak in the occasional memoir. Metta Sama’s first collection, South of Here, is so good. It’s published under her legal name, Lydia Melvin. I’m also really enjoying Nicole Sealey’s new book. Other poets – avery r young, Campbell McGrath, TC Tolbert. Luster by Raven Leilani is remarkable; I was floored by the daring plot, beautiful language, psychological complexity. That novel blew my mind. What else? I’m really into Michelle Tea, she’s influenced me particularly as a queer writer. What she’s written about sexuality and femininity is electric. The way she uses language is so bold and there’s this recklessness to her voice that’s raw, fierce, and crystal clear. I also loved Frank Wilderson’s memoir Afropessimism – so lyrical, so brave. It was a portal into the past and reanimated the present.

8. I read that you have experience teaching in prisons. At PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program serves writers who are incarcerated throughout the United States, and we receive letters from writers daily explaining the barriers they face with censorship and finding resources. What did you learn or become more aware of in regards to incarceration or the challenges writers face while in prison?

I learned a lot. There are so many challenges and yes, censorship and an absence of resources are major problems. But I’ve also witnessed in my incarcerated students a fierce urgency to write. Education becomes more potent behind bars – whether education comes through school or it’s autodidactic – people really want to learn. It’s a different ballgame in prison. Books are valuable because they’re heavily policed; yet so much can be done with some paper, pen, and imagination. It’s amazing.

There’s a stirring hunger that can arise when so much is stripped away; it’s so painful to witness. The hunger is also inspiring – there’s ingenuity, creativity, and wisdom which can come from the isolation of incarceration. What might be deemed trivial outside of prison becomes charged with meaning inside. Books, poetry, art – they hold more significance, I think, behind bars because they are harder to access.

“Rejection can breed tons of shame, but it can also make you stronger. I’m super tender, but I had to get tough as I wrote this work. So maybe I learned to be vulnerable and also be tough? I’m still learning how to be both because they are important to being an artist, being a writer.“

9. As a teacher of writing, what is one piece of advice you give to students?

Write into mystery. Write into fear.

10. Lastly, one of my favorite questions: What did you learn about yourself while working on this project, if anything?

It is such a hard question to answer. I got tougher, I think. I gained a thicker skin because I had to face so much rejection. Rejection from publishers, rejection from readers, rejection from audiences. There was also so much personal rejection. Rejection can breed tons of shame, but it can also make you stronger. I’m super tender, but I had to get tough as I wrote this work. So maybe I learned to be vulnerable and also be tough? I’m still learning how to be both because they are important to being an artist, being a writer.

Elisabeth Houston is an artist and writer; they work in text, performance, and video. Standard American English is her first book (Litmus, 2022). They live in Los Angeles and teach at Cal-State LA.

Safiya Sinclair | The PEN Ten Interview

For me, and for the women in my family, our stories are the way we preserve our history, our culture, and the vital parts of ourselves that our ancestors gave to us.

Mona Awad | The PEN Ten Interview

Really the novel explores how we often focus on the surface in order to avoid pain, or any kind of difficult, deep internal work.

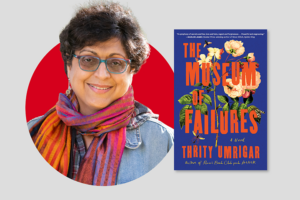

Thrity Umrigar | The PEN Ten Interview

Because what I’m most interested in is examining the systems and forces that create divides between people, those power dynamics that separate us.

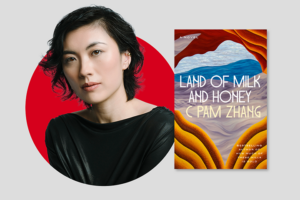

C Pam Zhang | The PEN Ten Interview

Like language, food is essential and theoretically accessible to almost anyone. The real question is which culinary voices are permitted, celebrated, amplified, valued.