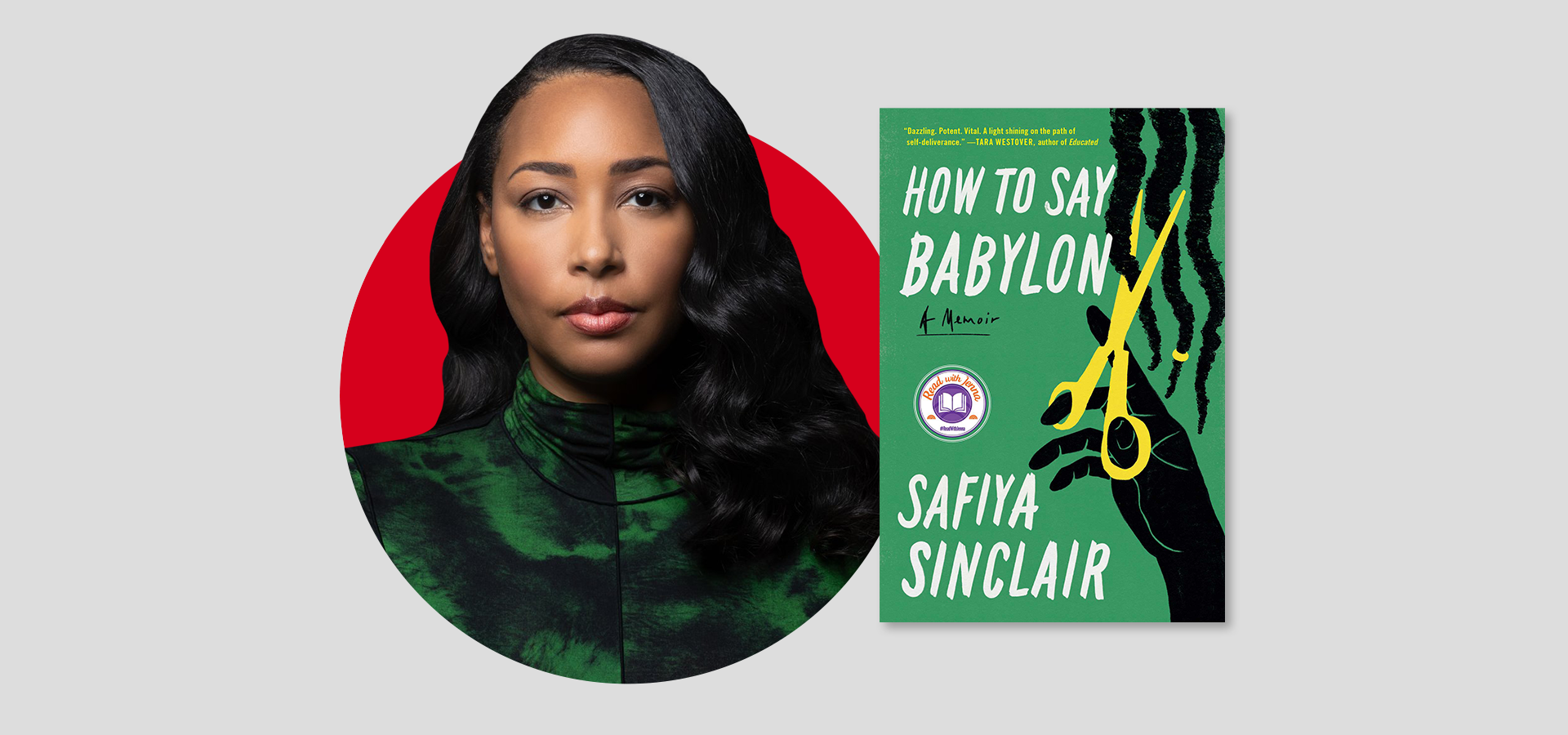

Safiya Sinclair | The PEN Ten Interview

October 18, 2023

In an exploration of home, Safiya Sinclair delivers a memoir that is honest, transparent, and brave in its grappling of Rastafari, family, and her future.

Like her name — “Clear-minded and pure. Beautiful” — How to Say Babylon is exact, musical, and meticulous in studying the relationship between father and daughter. In a conversation with Literary Programs and Emerging Voices assistant TC. Mann for this week’s PEN Ten, Sinclair shares details about her memoir, both unique in its Rastafari context and familiar in its themes—depicting the patriarchy, tradition, and Western World influences—and the inevitable collision that set her on a lyrical path. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. You walk a delicate line in this book, a bold yet careful one. Your ability to render scenes in their entirety yet love the people you write about in complete fullness is truly a gift. While reading, I often wondered about your bravery and if, at any point, you were nervous about this memoir existing in the world. Why or why not?

I was most nervous about my siblings reading the book. So much of the memoir was written in tribute to them and the love I have for them, and I wanted to make sure that when they looked into the pages, they would see themselves full-bloodedly, and feel the truth of our experiences. While writing, I consulted them on their memories of the places and people that shaped our lives, so the book itself would be a weaving of our collective memories, a record of the little world that the four of us built amongst ourselves.

2. There is so much tangled yet straightforward narrative of what occurred between your mother and father, you and your father, or your father and your mother’s sisters. What was your approach when researching and remembering your family’s history, and did it alter your remembered truth in this retelling?

I collected a lot of oral histories for How to Say Babylon. Oral folklore and storytelling are a vital part of Jamaican culture, and one that is largely matrilineal in my family. In writing this book, I wanted to save my mother’s stories—our family history—by writing them down, by making a record of our lives that says we were here, and that our lives mattered. While writing, I consulted my entire family and directly wove their memories and knowledge in the writing of the memoir. For my parents, there is an early chapter that describes their first meeting, which then follows them as adolescents who eventually decide to walk the path of Rastafari. In order to write that chapter, I recorded a lot of interviews with my parents that helped me flesh out the emotional velocity of their scenes, and would give the reader an insight into their interior lives. I consulted my siblings on many details of the homes we lived in, the people we met, and what happened in each house and when. I also consulted my family on the language of the book—both the definitions and spellings of Jamaican patois words, as well the unique lexicon of Rasta vernacular, were all constructed with their help. My family consists of natural storytellers, musicians, and poets, and they remember the details of our lives with painterly precision. I found that my memory and my own truth were only reinforced and enriched with my family’s crucial contribution, which was a gift.

“My family consists of natural storytellers, musicians, and poets, and they remember the details of our lives with painterly precision.”

3. One of my favorite images you continuously paint is your father’s musicality, him and his guitar, traveling by bus to the hotel to sing for the tourists. As a poet, how, if at all, has that shaped the way you rearrange, examine, and hear words?

My father’s musicality is his own kind of wildfire that differs from my own. As a reggae musician, his music is a form of prayer, as well as a form of protest. Reggae music is the means to spread the message of Rastafari. In many ways, my poetry is my own form of prayer, in the way that I follow the uncertainty of the lyric or the incantation of the image into an unknown place, into something that often feels bigger than me. However, I came into poetry as a way to nurture my own voice—at a time when my father desired only my silence. So, the music I developed as a poet was very much separate from him, it was a music that saved from the throttled world of his silence. Going forward in my work, I’m very interested in exploring the anti-colonial roots of Rasta dialect—a space that often excludes women—while interrogating the ways I can bloom a feminine perspective from its linguistic rebellion.

4. Before your memoir, when I thought of Safiya Sinclair, I thought of the poet, the deeply felt and melodic artist. How did the poet and memoirist find each other? Did you go through a process of learning to fit them both on the page?

The poet and the memoirist have always walked hand in hand. I’ve always written about the same themes in my poetry as I do in the memoir: family, Jamaican history, the rhythm of the sea, Jamaican womanhood and the unruly female body as a direct mirror to the landscape of the Caribbean. I wrote How to Say Babylon as more than an extension of my poetry, I also wrote it as a primer to read my poems. I’m just as concerned with the language and music in the memoir as I am in my poems, and I wanted each sentence in the memoir to sing, both on the page and if read out loud. Writing the memoir also allowed me to push myself as a writer: I had to outline the book before I began, which is something I never do in poetry. I had to learn how to create scenes, to shape the movement and cadences of dialogue, to explore world-building, character-building and constructing narrative arcs. And then there were times in the memoir where I just let the poet run free in the prose, dragging us along the jungle of her magics; to riff on hair for a long paragraph, to allow the reader to feel the bronze warmth of my mother’s hands, to feel the wind and salt-air of my island in your hair.

“I wanted each sentence in the memoir to sing, both on the page and if read out loud.“

5. You manage to move through so much time. The arrival of Haile Selassie, the departure of Haile Selassie. The arrival of you, the departure of you. How does time help shape this story?

I was really interested in time as a physical thread that pulled me through the memoir and its writing. I thought deeply about our oral storytelling and how in the Caribbean our stories and histories never manifest in a straight line; they are woven, they are circular, and the endings re-write the beginnings. I followed time as this red thread in the book—one that begins unravelling with the arrival of Haile Selassie, and one that I imagine myself pulling to recount our story, to understand where our story began. The book begins with a prologue of events that happen two-thirds of the way through the story, when I am a young woman looking into the future of herself and trying to imagine where following that red thread would take her. Time and again, I imagined myself severing this thread, authoring a new future. But eventually I decided to let go of history’s severing and unravelling; instead, by the story’s end, I wanted to pull this thread through the needle’s eye and stitch.

6. What was your creative process when exploring the different versions of Safiya? Which was your favorite version to relive and write in this project?

Poetry was my primary guide in reintroducing me to my younger self. Luckily, I’ve been writing poems since I was ten, so the poems of my youth were a perfect roadmap to revisiting and exploring different versions of myself while writing the book. Each poem from juvenilia anchored me in place and time to the girl I was when I wrote them. What were her fears, her desires? What did she dream of? It was all there on the page, full of glimmering details and imagery. Additionally, poems by other poets I treasured throughout my life were also excellent anchors in the process of diving into my memories. Music was also a very good container for memory, and the songs of my youth flooded me back to my adolescence in a very potent way. My favorite version of myself to relive on the page was my childhood self—that young girl running wild by the sea, learning to read the waves of the seaside that still calls me home.

7. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I love Jesmyn Ward, Raven Leilani, Nicole Sealey, Imani Perry, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Jericho Brown, Aracelis Girmay, Aria Aber, Bettina Judd, Paul Tran, and Danez Smith.

8. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Plato’s Symposium. I studied philosophy very seriously when I was in undergrad and I became obsessed with Plato’s Symposium, and all the different ways each philosopher at the gathering ruminates on the nature of love. For a few years I spent all of my free time analyzing and re-analyzing each speech in the text, and then began writing my own treatise on love.

“My favorite version of myself to relive on the page was my childhood self—that young girl running wild by the sea, learning to read the waves of the seaside that still calls me home.“

9. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Toni Morrison, though I’m sure she will be tired of terrestrial visitors by now. If I were in the presence of such a peerless mind, such a magician of language, I would just sit down and listen to whatever she had to say. I’d be interested in tracing and weaving all the connections between memory and music and language. I’d like to know what time of day the muse visited her, and what poem, of all poems, was her favorite. I’d like to know what she read when she needed inspiration. She once said “language is the measure of our lives.” After we have given all our good words, all our magics, our history in language, what, if anything, comes next?

10. Why do you think people need stories?

For me, and for the women in my family, our stories are the way we preserve our history, our culture, and the vital parts of ourselves that our ancestors gave to us. Storytelling is crucially rooted in the folkloric tradition of the African diaspora, and is connected to the way we navigate the land and the sea, and all the ways we love and remember each other. Without my mother’s stories, I would probably not be a poet and a writer. She taught me how to read the sea, she gave me my first book of poems, she gave me the history of our lives like a song, so I would not forget. I see it as my most crucial duty to keep this record of our stories, to write them down, so we don’t lose any part of ourselves. I write to pay tribute to the women who came before me, who first pushed their hands in the dirt and made me. I write so that whoever comes next will always know herself.

Safiya Sinclair was born and raised in Montego Bay, Jamaica. She is the author of the memoir How to Say Babylon, out from Simon & Schuster in October 2023. She is also the author of the poetry collection Cannibal, winner of a Whiting Writers’ Award, the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Metcalf Award, the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Poetry, the Phillis Wheatley Book Award, and the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry. Sinclair’s other honors include a Pushcart Prize, fellowships from the Poetry Foundation, Civitella Ranieri Foundation, the Elizabeth George Foundation, MacDowell, Yaddo, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, The Nation, Poetry, Kenyon Review, the Oxford American, and elsewhere. She received her MFA in poetry at the University of Virginia, and her PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Southern California. She is currently an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Arizona State University.

The PEN Ten Interview Series

Mona Awad | The PEN Ten Interview

Thrity Umrigar | The PEN Ten Interview

C Pam Zhang | The PEN Ten Interview