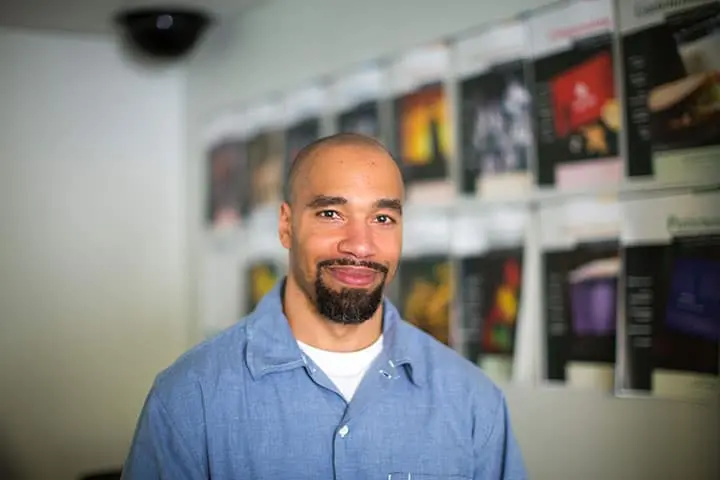

By Heather Lende

It’s a sunny July afternoon. Main Street in Haines is bustling, or as bustling as a no stop-light, fishing and tourist town that looks like Switzerland with beaches gets. The window is down, the radio plays country tunes and my dog rides shotgun as I park in front of the Olerud family market. My brother-in-law Norm, who learned to DJ in the Army and has volunteered on KHNS for decades, says it’s five o’clock somewhere and cues up Ken Chesney and Jimmy Buffet and I sing along.

Sharing the soundtrack to a happy afternoon of beers and sunshine may not convince Congress not to pull the plug on funding for KHNS and turn the lights off at our little station and others like it in rural places across the nation.

But this should.

Following nine months of Covid isolation on Dec. 1, 2020, an unprecedented atmospheric river of rain dropped 10 to 14 inches on top of many feet of melting snow, flooding homes and businesses in Haines, toppling trees and powerlines. Landslides blocked the road to the ferry terminal, and the dock where groceries arrive weekly on the barge from Seattle. It went from bad to worse quickly.

The ground turned to mush under homes and in yards, swallowing trucks and snow machines. My husband’s lumberyard and hardware store sold out of pumps and sandbags. We tuned into KHNS. Mayor Douglas Olerud left his store and was at the station to give updates and instructions. Multiple slides blocked escape routes and emergency response access; the road to the airport was out too, and the airport was flooded. Search and rescue teams from Juneau would land helicopters downtown.

We thought it was a once in 500-year event. We now know that’s not true.

The next afternoon, a huge slide crashed down on top of the Beach Road neighborhood. Trees, mud and debris from smashed houses floated in the cove near the lumberyard. At least six people were missing. Two would never be found.

At sunset, which in December is around three in the afternoon, I listened for news and instructions. Should we go or stay? Hillside neighborhoods were evacuated. More might be. The American Legion was open with food and clothing. The motels filled up. To heck with Covid, we opened our homes. Our daughter and her family, and my sister and Norm and their dog managed to walk around the gully that had been the only road to their neighborhood and get a ride here.

Our house was out of the danger zone, but what about everyone beyond the new slide, or past the ferry terminal? What about the people trapped? On the radio that dark, horrible afternoon a familiar voice, Marley Horner, the KHNS program director, said if you are cut off, if you live in the new slide zones and can walk, if your house is gone or going, help is coming. We won’t leave you. Commercial fishermen and the first responders are cruising the coastline on either side of town. “Go to the beach, shine a flashlight and a boat will come and get you.” Imagine all those lights in the darkness. The joy and grief. Imagine that.

I cannot, will not, imagine what could happen the next time, if KHNS isn’t here. And I’m sure other remote communities in Alaska and around the country whose populations have lived through floods, fires and storms no doubt are as fearful about the loss of their local stations.

Heather Lende was Alaska Writer Laureate 2021-2024 and the author of bestselling memoirs including Find the Good, If You Lived Here, I’d Know Your Name, and others about her experiences and observations in Haines, Alaska.