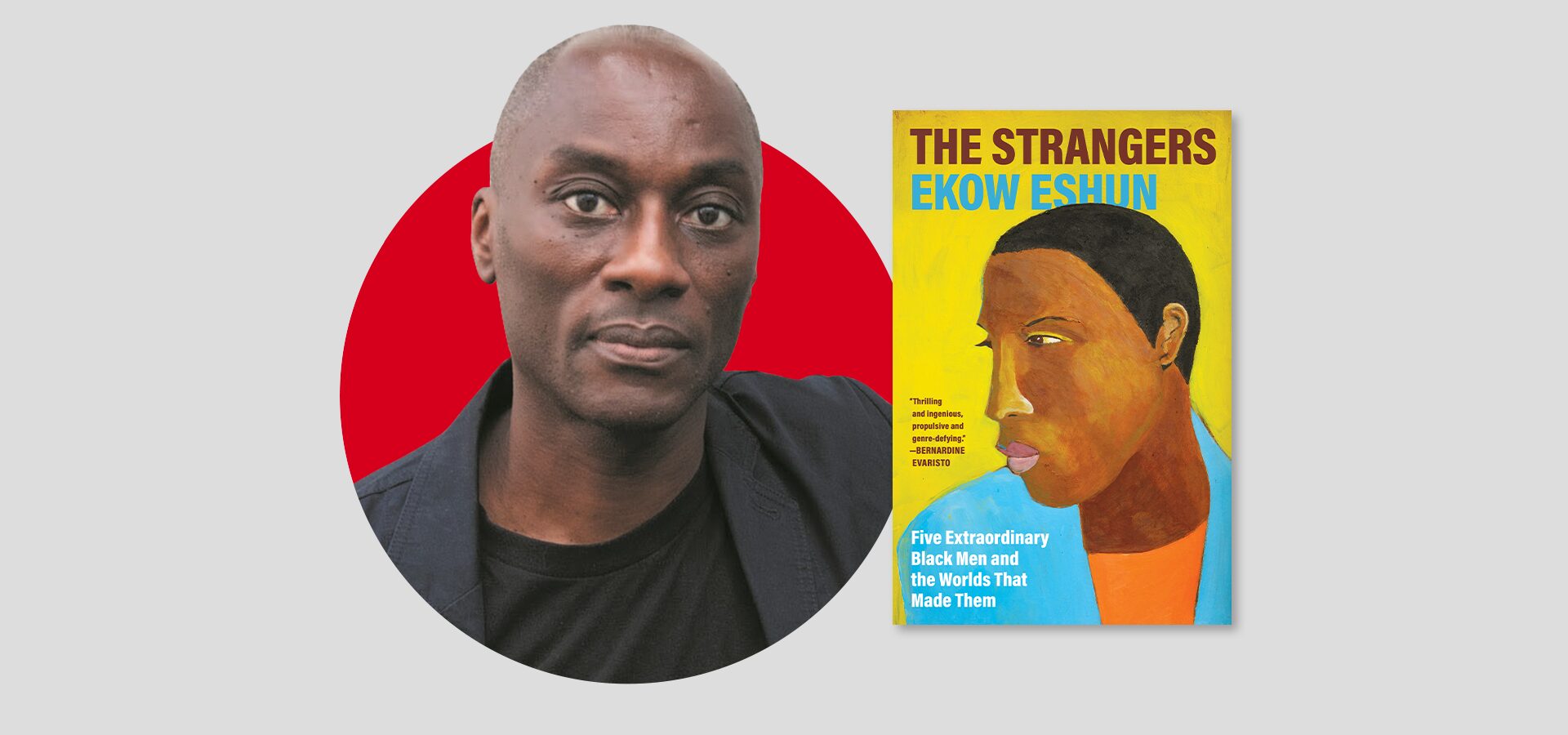

Ekow Eshun | The PEN Ten

In a scintillating tour de force, Ekow Eshun’s latest book The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them (Harper, 2025) interrogates the centuries-long social condition of Black men as strangers in the Western imagination through illustrative portraits of five noteworthy men: Ira Aldridge, Matthew Henson, Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, and Justin Fashanu.

In conversation with PEN America’s Government Affairs Liaison Christian Omoruyi for this week’s PEN Ten, Eshun reflects on the process and motivations that foregrounded his work of creative nonfiction; the dynamics and implications of stranger status that his Black male characters contend with; and the relevance of his literary exploration for Black men in contemporary civic life.

Plaudits to you for a magisterial book! How did you organize your literary process in writing this work of creative nonfiction?

From the outset, I knew that I didn’t want to offer exhaustive biographies of my five subjects—Ira Aldridge, Matthew Henson, Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, and Justin Fashanu—but rather to illuminate pivotal moments in their lives where they stood at existential and historical crossroads. That decision allowed me to focus in depth on periods of transformation, tension, and decision-making.

My process was rooted in a dual commitment: to historical fact and to emotional truth. While the documented details of these men’s lives provided a necessary framework, I also allowed myself the creative freedom to imagine the inner lives and emotional landscapes that the archive often omits—particularly in the case of Black men, who have too often been written as objects of history, not subjects within it.

I wanted to approach the Black interior as a space of possibility rather than definition, and to reimagine these men not just as historical figures but as deeply human beings navigating extraordinary constraints. This intent led me to adopt a second-person narrative voice, a stylistic choice that enabled a more intimate perspective—one that invites the reader not just to observe these figures, but to become them, if only briefly.

You reflect on W.E.B. Du Bois’ notion of double consciousness as seen in the superhero character of the Black Panther—“embodied alienation.” Du Bois discusses this sensation of “two-ness” from the perspective of a Black American. Given contrasts in structural racism among countries in the Anglosphere, would you identify any notable differences in how this manifests in the experiences of Black men in Britain?

The structures of racism in Britain and America differ in form. In Britain it’s often more insidious and covert. In America it’s arguably been more historically explicit. The alienation that can follow from that in Britain is particularly suffocating – that sense of being of a place but never fully belonging to it. It’s an attitude summed up very neatly by our Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s despicable pronouncement recently that immigration risks turning Britain into ‘an island of strangers.’

With that said, I’d argue there’s less that separates the experience of Black people in Britain and America than unites it. The racial othering that defines Black experience in the Anglosphere—whether in the form of American segregation or British bigotry —is, at its core, a refusal to see Black people as fully human.

In the book, Frantz Fanon has an epiphany while working at the psychiatric hospital in Blida, Algeria, that adopting culturally literate methods of treatment would better help his patients, lamenting that “colonial delusions are hard to shake off.” How does Fanon’s time in French Algeria illustrate the pitfalls of ideological assimilation, even among Black men conscious of their social position as outsiders?

One of the reasons that Fanon remains such a resonant figure in culture and ideas is his extraordinary journey from colonial subject to revolutionary thinker. Despite his very personal awareness of the psychic harm of racism he initially approached psychiatry through the lens of the colonizer. Only through his direct experience in Algeria did he come to reject these frameworks. He went from seeing his Arab and Berber patients as the Other, as he’d been taught all his life, to embracing them as kin. For Fanon, revolution began in the head.

I wanted to approach the Black interior as a space of possibility rather than definition, and to reimagine these men not just as historical figures but as deeply human beings navigating extraordinary constraints.

There was a certain poignancy in your recounting of your own dreams and nightmares, a testament to how the status of ‘stranger’ can transcend wakefulness. In your inquiry for this book, did you encounter fellow strangers of color—contemporaries or those from the historical record—who also grappled with their dream lives?

Writing the book brought me closer to the awareness that the experience of being regarded a stranger isn’t limited to external circumstances—it infiltrates the interior, even the dream life. Surprisingly, though, I didn’t encounter other figures that have documented this explicitly through their dreams. Although I guess you can make the argument that a whole raft of books, from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man to Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad are essentially journeys through dreamscapes/nightmares.

You discuss progressive evolutions in the lyrical expression of Black masculinity beyond popular caricature by prominent hip-hop artists. You specifically commend Jay-Z for his “open embrace of vulnerability, a reckoning with love as the signal marker of Black humanness.” Your commentary prompted me to revisit Kendrick Lamar’s album “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers.” Have you observed a trend of other artists following suit?

In writing about Jay-Z, as well as the likes of Nas and Mobb Deep, I was interested in hip hop artists who came to the fore in the 1990s and how the hyper masculinist ethos of that era provided them a space of opportunity and an environment of constraint. Hip hop culture has happily moved on since then to allow for greater emotional transparency among its artists. You definitely see that in Kendrick. And also in the likes of Tyler, The Creator, J. Cole and Kid Cudi, who speak more candidly about depression and vulnerability than would have been fathomable a couple decades ago. That’s not to say that the ‘90s lacked introspection. Artists like 2Pac, Nas, and Scarface did explore pain and inner conflict but the emotional spectrum was narrower, with vulnerability largely sublimated into anger or masked by bravado.

In Malcolm X’s final reflections shortly before his assassination, he expresses regret about his stinging rebuke of Maya Angelou when they first met—she had asked him to join a protest. In what ways does the social othering of Black men you elucidate impact their relations with Black women?

In The Strangers, I explore how the social othering of Black men—our persistent casting as alien or incomplete—creates an emotional burden that shapes not only how we are seen by the world, but how we relate to those closest to us. The way Malcolm treated Maya Angelou when they first met speaks directly to this: a moment where the psychic toll of racialized masculinity occluded the possibility of solidarity and mutual recognition.

Part of the reason I wrote the book to begin with was to try to reach beyond those limited perspectives on maleness and to depict men as emotionally complex beings shaped by history yet striving to define themselves on their own terms. A big inspiration was the work of Black feminist scholars like bell hooks, Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe who’ve been essential to the larger project of articulating Blackness and being by pushing the discourse beyond survival toward possibility.

In The Strangers, I explore how the social othering of Black men—our persistent casting as alien or incomplete—creates an emotional burden that shapes not only how we are seen by the world, but how we relate to those closest to us.

I appreciated the ontological and disciplinary diversity of the five men you profiled. Were there other Black men of distinction, of both renown and obscurity, who you also weighed featuring in The Strangers?

There was a whole bunch of figures that didn’t make the final cut for a variety of reasons. I considered writing about Michael X, the 1960s leader of the British black power movement. But he was also a pimp, a conman and a convicted murderer and just too unsavoury a character for me to live with for a sustained period of time. I also thought about James Baldwin during the decade when he lived on and off in Istanbul, beginning in 1961. Happily I came to my senses and realised that would be a fool’s errand – Baldwin didn’t need anyone’s help to write about his interior life.

You are not only a bracing writer, but a celebrated curator. In your exhibitions, by what means have you interrogated the reality of the “legacy of caricature” that you contend each Black man inherits?

It’s a joy working with artists because they have the capacity to invoke worlds of possibility and wonder, of strangeness and depth, often without using any words at all. I learn a lot from them about how to evoke feeling, mood, tone. I curate exhibitions at museums and galleries around the world and my mantra is the same with each project: show, don’t tell. When I’m dealing with Blackness as a subject, for example in a large group show like “The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure,” then I’m bringing together works that are summoning visions of Black beauty and dreaming and richness and complexity. All of it antithetical to that legacy of caricature and all of it dedicated to articulating what the scholar Kevin Quashie calls “Black aliveness” – that is, the invocation of Black being as a multiple not singular state, a condition of endless possibility.

What did you enjoy the most about writing this book?

Good question. The book took about five years. Which meant that for a year at a time I was either living, in my head, in revolutionary Algeria with Fanon. Or early 19th century London with Ira Aldridge. Or trekking to the North Pole at the turn of the 20th century with Matthew Henson. It was hard going at times. But in the end it was a joy to spend time with these men. And I hope I did them some justice in telling their stories.

I tend to feel double consciousness can also be seen as a kind of gift. It grants a sharpened perspective—a capacity to see the world with a depth and nuance often unavailable to those not forced into a daily reckoning with their own personhood.

In the wake of your assessments of the men in your book, how would you counsel Black men to reckon with their status as strangers in the West without forsaking their capacity for joy and hope?

The men I write about each lived at the edges of belonging. They were exiles, outsiders and pioneers. Yet with that outsiderness, there was also a kind of freedom: a space to imagine oneself otherwise.

Back in 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois coined the term double consciousness to describe the “peculiar sensation” of living as a Black person physically within, yet psychologically outside, white society. For him it was a painful proof of the exclusion of Black people from the heart of society. I tend to feel double consciousness can also be seen as a kind of gift. It grants a sharpened perspective—a capacity to see the world with a depth and nuance often unavailable to those not forced into a daily reckoning with their own personhood. A reckoning with strangeness in these terms becomes a routeway to self-authorship. It is a refusal to be reduced or erased. It is an assertion of the right to complexity.

Ekow Eshun is a British writer, curator, broadcaster, and author of the memoir Black Gold of the Sun, which was nominated for the Orwell Prize for its exploration of race and identity. He writes for the New York Times, the Financial Times, and The Guardian, and has created documentaries for BBC TV and radio. Eshun was the first Black editor of a major magazine in the UK and the first Black director of a major arts organization and has curated exhibitions internationally. Described by Vogue as ‘the most inspired—and inspiring—curator in Britain’, he is Chairman of the Fourth Plinth, overseeing Britain’s foremost public art program. He lives in London.