Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Georgia quickly emerged as the poster child for democracy in a tumultuous part of the world. For three decades, the South Caucasus country enjoyed industrial and cultural growth supported by a free press, a dynamic parliament, and an engaged civil society. It also weathered several significant challenges, including the ongoing Russian occupation of about 20 percent of its territory.

Yet today, just days before crucial parliamentary elections, Georgia appears to be sliding back into a Soviet-style authoritarian regime, with democracy and civil liberties in dramatic decline. This summer, the Georgian government made sweeping legislative changes: from the smearing of NGOs as “foreign agents,” to censorship and criminalization of LGBTQ peoples’ rights in the “family values bill,” and promises to ban opposition parties. The Georgian Dream-led government has conjured nightmares, handing down serious penalties for free expression and cultural independence.

So what went wrong? How did Georgia change course so quickly?

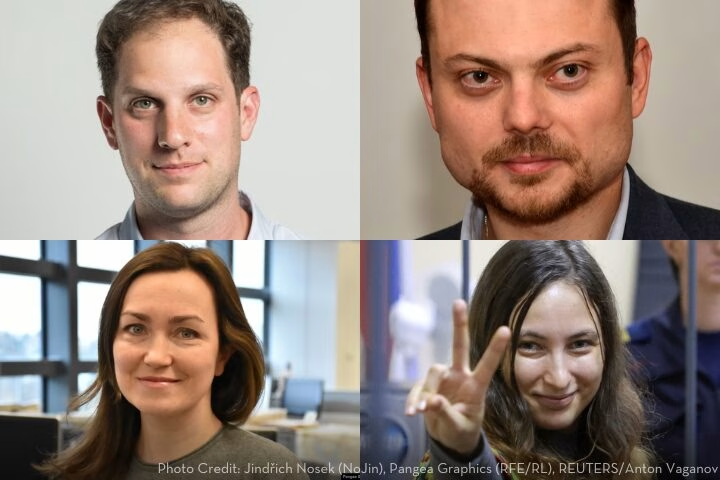

PEN America’s report Taming Culture in Georgia: Georgian Government Clamps Down on Freedom of Speech and Cultural Expression offers some answers to these questions by providing case studies of government threats against writers, artists, and cultural workers and its ongoing suppression of free expression. The timeline starts over three years ago, when Tea Tsulukiani—a senior member of the Georgian Dream—was appointed as minister of culture, sport, and youth. Her appointment kicked off an escalated government campaign of suppression of writers’ and cultural workers’, resulting in, for example, the politically-motivated firing of the head of the Writers’ House of Georgia.

Late last month, Georgian writers Ekaterina Togonidze and Lasha Bugadze, along with Taming Culture in Georgia report author Polina Sadovskaya, met with key U.S. officials and other influential figures, seeking increased support for Georgian civil society, in particular writers and cultural sectors. While in New York, Togonidze sat down for a conversation with PEN America staff about democracy and culture in Georgia. She was joined via video by PEN Georgia President Khatuna Tskhadadze.

Here are some takeaways from the fascinating discussion, which have been condensed for clarity and length:

Georgian society has weathered many challenges since independence; how do you feel about your ability to withstand the current democratic backsliding?

Ekaterina Togonidze: “I was born in the Soviet Union. We had wars, civil wars, hunger, no electricity, cruelty. But we always knew in which direction we were moving, that our goal was integration into Euro-Atlantic structures and freedom was our main value. Now that the world is open and everybody knows what it’s like to be free, they no longer know what it is like to be a slave. My daughter has only known freedom.

“Instead of telling the truth about the Soviet lifestyle, the Georgian Dream has created a new lie, saying they are protecting us from a perverted world. And they are pushing the buttons of fear, saying to Georgian people, ‘Your children will be perverted. You won’t multiply and survive’.

In our report, we highlighted the Writer’s House in Tbilisi as a vital hub for Georgian writers and artists, which was being taken over by the Ministry of Culture. What is the situation today?

Ekaterina Togonidze: “One early sign of the cultural clampdown was the government’s intervention in the independent literary prize Litera hosted by the Writer’s House, where legal maneuvers were used to oust its executive director Natasha Lomouri and install a government-friendly leader. The Writer’s House is now boycotted by leading authors who have united under the PEN umbrella in protest.”

Khatuna Tskhadadze: “The Writer’s House used to be a happy place for writers and younger generations, an island of freedom of speech and artistic expression. Today, artists are considered ‘dangerous people’ by the government and we no longer have our Writer’s House.”

Despite mass protests, Georgia’s “Law on the Transparency of Foreign Influence,” better known as the “foreign agents” or “Russian” law, recently went into effect. It mandates that civil society and media organizations receiving more than 20 percent of their funding from foreign sources must register under a “Foreign Influence Agents Registry.” You have been outspoken against this law – why do you believe it will be so harmful?

Ekaterina Togonidze: “This law means organizations have to label people, they have to provide personal information about everyone who works there and who they interact with, including their religious views and medical or sexual information. People are scared to do this. If we register as a ‘foreign agent,’ no one will come to our events or give us a venue.”

Khatuna Tskhadadze: “‘Why don’t you want to be transparent?’ the government asks us. But of course, NGOs already have to be transparent! They can ask us everything about PEN, for example, they can see everything on our website.

“Many organizations are relocating to Baltic countries. Others are waiting for the elections. I think the situation will dramatically change after the election – we are now in limbo, waiting.”

At PEN America, we understand the power writers hold in promoting openness, independent thought, and visions of a better future. And we regularly see how autocrats instinctively recognize this as a threat and are quick to silence dissident voices. Is there an official censorship program in Georgia today?

Ekaterina Togonidze: “There is no official blacklist accessible to the public, but we are seeing and experiencing it. For example, how invitations to hold speeches are withdrawn, grants for projects are suddenly canceled. I am often asked to self-censor my writing, the most recent time was in September for an op-ed I wrote about Abkhazia. They asked me not to criticize the government because it would make the piece become too ‘political.’

“And it’s only getting worse, for example with the new anti-LGBTQ law. I was invited to be on the jury of a prestigious journalism award, and now we are really confused about how to evaluate works that talk about sexual minorities, which is now illegal. The same with literature, it is now forbidden to write about so many things!”

What are your expectations for the Georgian Dream party in the upcoming elections?

Ekaterina Togonidze: This is the first time when there are no election promises, they don’t promise us that they will build something or improve our lives., There is nothing positive in their campaign, instead they promise to arrest everyone who is against them. They promise to ban opposition parties. They call us Nazis (this is their label for the name of the largest opposition party, the National Movement).

“So if we are against this crazy regime and even on the blacklist, it is now a matter of pride!”

Khatuna Tskhadadze: “The government has also made clear that cultural output—books, films, and other media must be ‘patriotic,’ which means it is aligned with Georgian ‘traditional’ values. Minority voices and LGBTQ are being silenced.1 In September, just one day after the passage of a major anti-LGBTQ bill, Kesaria Abramidze, a well-known transgender singer in Tbilisi, was stabbed to death.

“It’s very dramatic to see how fast things spiral.”