In the past few years, generative artificial intelligence has become a larger part of the political conversation. Voters have had to learn about deep fakes and cheap fakes and how to identify them. They’ve had to evaluate whether a video clip is actually false, or whether the politician at the center of it is exploiting the public’s skepticism and only claiming it’s false. They’ve seen op-ed after op-ed offer conflicting advice on whether AI will ruin the world as they know it, or whether the panic is completely overblown.

Generative AI was at the center of a nuanced and wide-ranging conversation held by PEN America earlier this month that also touched on encrypted messaging apps, foreign interference operations, social media platforms, and declining distrust in institutions.

The panel was moderated by Nina Jankowicz, an author and researcher who leads the American Sunlight Project, an advocacy organization focused on fighting disinformation. Panelists included Roberta Braga, founder of the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas; Tiffany Hsu, a disinformation reporter for The New York Times; Brett Neely, the supervising editor of NPR’s disinformation reporting team; and Samuel Woolley; a University of Pittsburgh professor and disinformation researcher.

Five weeks before Election Day, the panelists discussed the most dangerous disinformation threats they were seeing in their work. These ranged from increasingly sophisticated foreign influence campaigns to fatigue among content moderators on social platforms, to an inability to get credible news to people who live in seemingly impenetrable informational bubbles.

“It’s like pollution, and we’re on a smog alert cycle,” Neely said. “Even something as preposterous as the claims around immigrants in Ohio eating pets took sustained debunking — and even then you never saw anyone withdrawing their claims. You just kind of moved on.”

A lack of content moderation on social media isn’t helping. After he took over Twitter and renamed it X, Elon Musk eliminated most engineers dedicated to trust and safety. Many of the safeguards put in place after the 2016 election on social platforms have been dismantled in the past few years at companies such as Google and Meta, and research into online disinformation has been eroded.

For Hsu, rising disinterest in content moderation is one of the most alarming recent disinformation trends. There is a rising sense of fatigue as the platforms are attacked by both parties for their shortcomings and policies, shesaid.

“It’s very concerning because without transparency, without comprehension of what’s driving changes in the quality of discourse, we can’t adapt these platforms for the better,” Hsu said.

The disinformation campaigns on these platforms are also becoming more sophisticated – and not just technologically.

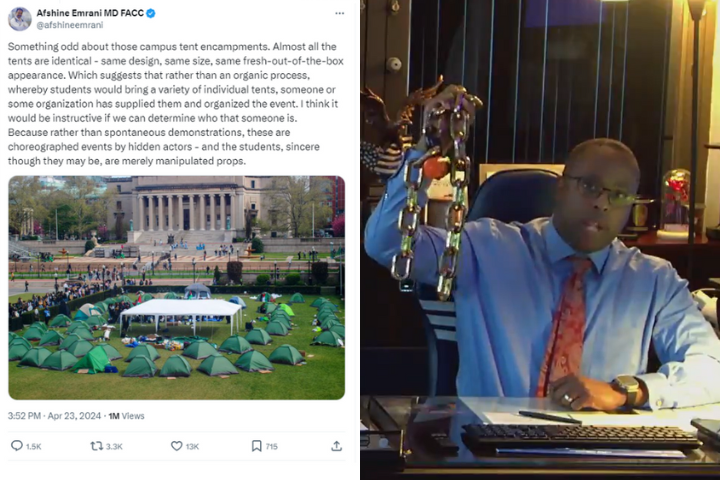

The disinformation campaigns on these platforms are also becoming more sophisticated – and not just technologically. False narratives are becoming more personal, specific and harder to spot. The messengers are evolving, as well, as social media influencers are paid to spread hyper-partisan content without having to disclose what they’re doing. Braga mentioned the oversaturation of this type of content on online spaces where people spend a lot of their time, such as YouTube or WhatsApp.

“More and more of that content is not outright false or even easy to identify as false,” Braga said. “It’s just massively decontextualized or uses one little grain of truth and manipulates it so aggressively that people take that story about the state of the world and build into it.”

This particularly appeals to people who already are politically involved or conspiratorial, Braga said. Heightened awareness of disinformation can also dampen societal trust. This can be good and bad, she said – people are questioning false information, but they’re also questioning credible information. And the sense that nothing is real often benefits manipulators.

“Propaganda is not necessarily often about persuasion,” Neely said. “It is about making you question whether anything is authentic and inspiring a sense of cynicism that encourages people to lose faith in institutions and information and to withdraw into a personal sphere and not participate as much in the political realm.”

Disinformation campaigns can also benefit those who have something to hide. When it’s unclear what is real, it becomes easier for the subject of an unflattering news cycle to capitalize on the public’s distrust and confusion. This concept is called the liar’s dividend, which Neely called the most significant part of the AI revolution, at least right now.

Jankowicz cited former president Donald Trump’s false claim that Vice President Harris’s crowd sizes are AI-generated as an example. The claim is about more than crowd sizes and ego – it starts to sow doubt among his supporters that Harris really has the support she claims to have, creating the potential for people to question her victory if she wins in November.

Some experts have claimed the panic over AI is overblown. Woolley called this line of thinking “backlash” to the spate of op-eds claiming “the sky was falling” as deep fake technology advanced. He urged people to remain measured, saying propaganda is often a sociological phenomenon and that it’s difficult to measure the true effects of day-to-day disinformation in a controlled experiment that would satisfy social scientists.

Hsu added that a lot of reactions to new technology like AI are emotional, raising the example of false claims about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio. The images or videos that were obviously fake might not have fooled anyone familiar with technology.

But it’s the volume of images moving through online spaces, she said, that creates the sense “this is a topic we can make fun of” – that it doesn’t need to be taken seriously.

“What that does is it damages trust in the information ecosystem,” Hsu said. “It also makes the underlying message that what’s happening in these communities, the targeting of these immigrants, is a laughing matter – this is not something we should worry too much about.”

Braga said AI isn’t going to be a huge game-changer in “duping” someone into behaving a certain way or believing something they didn’t already believe. But, she said,it will be co-opted to advance certain goals, using the same manipulation tactics already used to deceive: fear-mongering, cherry-picking and using emotional language.

Disinformation often exploits existing prejudices. The false narratives around Harris target her race and gender, and the outlandish claims about Haitian immigrants are clearly meant to supercharge existing anti-immigrant sentiments.

Braga said her organization, Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas – which focuses on Latinos and Latin America – is also seeing a rising level of skepticism of institutions. The most widely penetrated narrative her organization is seeing is that corporations are all-powerful in the U.S., lessening voters’ ability to make an actual difference in politics.

Minority communities are “not extra susceptible, and we’re not gullible, and we shouldn’t be talked about that way,” she said. “But there is an existing distrust in elites and institutions that plays a huge role.”

As for how to handle the AI revolution and hyperspecific, targeted disinformation campaigns, the panelists acknowledged that every fact-check and debunk can sometimes feel like a drop in the bucket. Hsu emphasized the need for transparency among journalists who are combating or covering disinformation – it’s important to not only do the fact-checking, but also explain it.

“I often say that I end up spending more time fact-checking and bulletproofing my stories than I do reporting them,” Hsu said. “Just because what I and my team have to put out there gets scrutinized in such a way that we need to be able to back up literally every word that goes into a story.”

She added: “I think just taking very, very great care in how we’re expressing what we know and what we don’t know is a big part of it. … A lot of journalists assume that readers or audience members understand how we’re producing a final piece of content when that’s probably not the case.”

And amid what Woolley called a “race to the bottom by social media platforms” in responding to disinformation, the panelists expressed hope that interventions can work and there are lessons to be learned from around the world on how to build resilience against online falsehoods.

Woolley ended on the note that misinformation is particularly potent “when it comes from someone you care about.”

“But the solutions to these problems are also particularly potent when they come from someone you care about,” he added. “That’s where the power really, really lies, it’s in our relationships and our abilities to work together to solve these kinds of issues.”