Dimitri Nasrallah | The PEN Ten Interview

August 29, 2024

Dimitri Nasrallah’s latest novel Hotline (Other Press, 2024) offers a stirring look into the immigrant experience, drawing from personal history and collective experiences of deracination and adaptation. Set in the 1980s, Hotline follows the protagonist, Muna, through her first 12-months in Canada after fleeing civil war in Lebanon. Recently widowed single mother Muna is harshly welcomed by a brutal Montreal winter. Forced to navigate an inaccessible job market while raising her son Omar alone, the novel explores how she must adjust to a life determined by the assumptions of others. Inspired by the author’s personal history, this novel is a peek into the vulnerable, the lonely, and the mundane moments of the immigration experience.

In conversation with the World Voices Festival & Literary Programs Intern Esmé O’Brien Smith, Dimitri Nasrallah discusses his own childhood memories, the intricacies of language in a transitory state, and the universality of beginning anew. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

1. Hotline is a novel that contains multitudes. You explore the themes of motherhood, immigration, isolation, language, and violence, to name only a few. In your writing process, where do you begin when writing such a multifaceted story?

The inspiration for this novel comes from my family’s first year in Canada. At the time, we had been accepted for immigration after seven years of living in Greece and then Dubai. We had left Lebanon quite abruptly in the early 1980s during the Israeli invasion of Beirut portion of the civil war, and were accepted to live in Quebec based largely on my parents’ French skills. But once we got there, my mother, who is a French teacher by profession, was unable to find a job in that field.

After many months, she had to settle for the only job that would have her, which was working at this weight-loss centre where they sold pre-packaged food from catalogues. So this story, of coming from civil war only to end up contending with these unexpected challenges in this new society with its own language and nationalism debates underway, was borne from her circumstances. They ended up leaving their mark on me as well, and affected our relationship for many years after.

2. You draw from deeply personal experiences in your latest work. These personal touches are central to the story; did you feel as though you were sculpting your own memories into fiction? What difficulties come along with that practice, and what did you learn?

When the novel was first published in 2022, one critic noted that I had written a first novel for my fourth, in that this kind of personal approach is the type of thing that comes out when writers are young and working out their personal histories. But I wrote this book in my early 40s, more than three decades removed from the events that inspired it. I began with these diet-plan food packages that showed up in our apartment, and which sometimes ended up in my school lunches. In writing their story, I realized I was writing a version of my mother’s story, something I had never done before.

The fact that I’d avoided writing about that before revived for me some of the challenges we’ve had in our relationship over the years. Those boxes showed up at a time when I only ever saw her as someone who was stressed and impatient and preoccupied. That built up into anger in me. Three decades later, after becoming a parent myself, I knew the reality was that she had had to contend with these societal challenges that I couldn’t see at the time. It seemed like the right time to tell that story, to put this period of our life to rest. Things haven’t changed much in Quebec since, where anti-immigrant sentiment continuously pushes through into discriminatory policy, often affecting teachers.

“Once I settled on Muna and began writing from her voice, this entire world came to life. Her voice belonged to the Lebanese women I’d known growing up. That voice became the heart of the story for me, and I wanted readers to feel they really knew Muna inside and out, in a way that real life would rarely afford them. In using that voice, I was also communicating with my mother in a roundabout way, to let her know that I see things differently now.“

3. One thing that I both find interesting and admire about Hotline, is that your protagonist Muna feels deeply isolated. However, you were able to deftly craft other characters and seamlessly incorporate them into the story without writing from their perspectives. Why did you choose to tell the story using Muna’s voice, and hers only? Why not from Omar’s perspective, for instance?

My second novel Niko, published eleven years earlier, had covered the move from Lebanon to Canada from a young boy’s perspective, so I was conscious of not wanting to repeat myself. Once I settled on Muna and began writing from her voice, this entire world came to life. Her voice belonged to the Lebanese women I’d known growing up.

That voice became the heart of the story for me, and I wanted readers to feel they really knew Muna inside and out, in a way that real life would rarely afford them. In using that voice, I was also communicating with my mother in a roundabout way, so let her know that I see things differently now. After she read the book, she said it was the first work of mine she’d read that didn’t feel like I was angry anymore.

4. Muna works, specifically, as an operator at a weight-loss hotline (hence the name of the novel). She is immediately successful in the field, selling record numbers of meal plans and cultivating lasting relationships with her clients and her boss, Lise Carbonneau. Could you speak to the connections between being a hotline operator and some of the less obvious aspects of the immigrant experience?

Early on, after I’d established Muna and her work at the weight-loss centre, I came up with the idea of adding a hotline to the business model. Hotlines were all the rage in the 80s and well into the 90s, before the internet – and now AI – evolved the ways we connect with others. Immigration was way more isolating then. It was often very costly to call home and there was no way to keep in touch with your culture other than through a similar community where you’d landed. So this idea of the hotline as a way for isolated people to connect with others visualized one of the major themes of the story for me.

The hotline gave Muna a way to speak without being seen. The people who are calling the hotline are facing social stigmas regarding their body image, and Muna is facing her own discrimination as a newly arrived immigrant. Fatphobias and xenophobias – both of the visual discriminations are eliminated on the hotline, where people are able to make connections with only their voices.

5. Louis Laflamme and Sylvie Leduc are the two main clients that call Muna’s weight-loss hotline. We readers get to know them just as Muna does, yet there remains a perpetual sense of one-sided intimacy. Could you speak about how that relationship, from caller to operator and vice versa, may in fact be somewhat like an act of translation?

With Louis and Sylvie, I wanted to showcase the alienation of modernizing society and how it leaves so many people quietly on their own. Hotlines in that era offered people connectivity and a sense of community, for a price. It was procured and completely one-sided; Muna cannot reveal anything about herself, not even her real name, for fear of either breaking the illusion or creating a false connection or pushing the customer away. She’s there on the outside to listen, to discern and offer back what this society needs. It is an act of translation because Muna must read these customers if she is to keep the relationship going, and she must understand their feelings and offer back a summation of therapy in order to build trust.

“The hotline gave Muna a way to speak without being seen. The people who are calling the hotline are facing social stigmas regarding their body image, and Muna is facing her own discrimination as a newly arrived immigrant. Fatphobias and xenophobias – both of the visual discriminations are eliminated on the hotline, where people are able to make connections with only their voices.“

6. Speaking of other characters, I found Lise Carbonneau to be a particularly fascinating character. Muna’s feelings towards her are complex: there are feelings of admiration and intimidation, camaraderie and inadequacy. What do you feel Lise Carbonneau represents in the novel? Were you writing her character with any person or type of person in mind?

Lise was a fun character to write! I got to play around with these popular philosophies of self-actualization and the business models that were built around them at the time, which is how this sort of commission-heavy work is often pitched. A person can control their own financial fate, if only they can solve the puzzle of their client base. This is what Lise has done, moved herself away from the cosmetics counters of a large department store and into the managerial sphere of a budding industry, which at the time was still looked down upon as a scam and pushed to the side as “women’s work”.

For Muna, who has so few access points into Montreal life, Lise is a success story, an embodiment of who she can become if she does well at this job. It’s her way of remaining optimistic even as she drifts further away from her chosen path of teaching. The big difference, of course, is that Lise is white and blonde and the ideal of what this 80s society wants from women, and Muna is none of those things.

7. There is a mystical aspect to Muna’s character, as she frequently conjures up the apparition of her disappeared husband Halim in times of need. Despite maintaining her grip on reality, this imagined Halim helps Muna cope with her isolation. How did this hallucinatory relationship materialize in your story? Was it inspired from your own experiences with grief?

I wouldn’t quite call it mysticism or conjuring or hallucination so much as Muna letting her mind wander, often after stressful episodes, in a world that doesn’t allow her many reprieves. The fate of her husband is an unresolved void in her life, and in many ways it’s holding her back from fully letting go of Lebanon and investing herself in the present that she was supposed to share with him. Muna’s exchanges are with a consciously idealized version of this imperfect man she married. There’s no one to tell her not to indulge these episodes, and she needs to speak to her mind after long days of being a consoling ear and voice to others.

8. To me, the Montreal weather is almost a full character in your novel. Nature intimidates, threatens, and limits. Most importantly, the weather serves as a constant reminder of the characters’ new lives. Is there a metaphor between the harshness of a Canadian winter and the sometimes quiet violence of the immigrant experience?

The space of a novel should always function like a character and not merely a backdrop. We interact with the places we inhabit, and they push and pull us along the way, shaping who we become. Especially in a new city like Montreal, which is so drastically different from Beirut in almost every way, the language politics, neighborhood divisions, and weather are going to call into question every assumption a person has about how to live. It certainly was that way for me and my family when we first immigrated to Canada, especially the harsh climate. Montreal is a city where the conditions can change quickly every few hours. This is perhaps the most universal aspect of the immigrant experience for anyone who tries to make a life there.

9. The concept of translation plays a large role in this novel and in your career. As the editor of Esplanade Books, the fiction imprint of Vehicule Press, and as a working translator, how do you feel your professional experience with international (and intercultural) literature shaped your experience writing, and how it shaped the content of Hotline?

As an editor, I think a lot about “decolonizing” the editorial process, or simply being more aware of where certain books are coming from and not trying to prescribe an approach to how they will be edited that will reduce them and their authors’ intentions. When it came to Hotline, I was able to apply some of these ideas quite practically to the interplay of different languages in the novel. This is a story told in the first person by a woman who thinks in Arabic and communicates in French, all while having the story related in English. Often, novels featuring a second or third language will go out of their way to signal it to the reader – an italicization, quotations, footnotes, or even a quick follow-up translation embedded in the text. That in itself, it occurred to me, was a colonial approach that prioritized the English mindset as the basis of all assumptions. But it’s not how a multilingual person would operate, dipping in and out of pockets of language fluidly, as required.

So in editing this story, we decided that the Arabic and French would appear without demarcations, and that the reader would do a little extra work of eventually figuring out what it meant from context. And readers have reacted positively to that approach. The use of language has become one of the points of discussion for the book, and people have seen in it the ways their families or extended families will normally function across languages.

“The space of a novel should always function like a character and not merely a backdrop. We interact with the places we inhabit, and they push and pull us along the way, shaping who we become. Especially in a new city like Montreal, which is so drastically different from Beirut in almost every way, the language politics, neighborhood divisions, and weather are going to call into question every assumption a person has about how to live.“

10. In your book, you write “C’est une langue secrète, the art of understanding what isn’t said.” Not only is this a beautiful line, but it illustrates the significance of language, comprehension, and communication in your novel. Your writing flows seamlessly between French, English, and Arabic. What inspired you to keep those barriers fluid? Did you model this choice after any specific text you’ve read?

Keeping those barriers fluid came from the increasingly prevalent reality of living in multilingual worlds, where people will speak one language with their families and another outside the house, or where some vocabulary will jump the language line and become recognizable in another language. As someone who has operated in more than one language ever since I was very young, it has always felt limiting to fit into an “English” frame of reference. With this novel, my fourth, I decided I wasn’t going to do that anymore and just take the risk of being who I am, even if French can be intimidating to English readers and Arabic is quite far off from both of them, to say nothing of the barriers to Arabic in the West that go far beyond linguistics.

11. In other interviews of yours, you’ve been asked about what defines Canadian and/or Quebecois literature. You once said that “Quebec literature takes imaginative and aesthetic risks, pulling in strands from both the English and French literatures of the world.” Considering the fact that Muna does not speak English, why and how did you decide to tell her story in English, as opposed to French or Arabic?

When I was five years old, my family left Lebanon on a boat with only a few suitcases with us. We started a new life in Greece, where I attended an American international school that was frequented mostly by the children of US troops and diplomats stationed there, as well as international students who didn’t fit into the Greek education system. That’s where I first learned English, and where English eventually became my primary language.

As the war drew on and the prospect of a return diminished, my parents thought it would be better for us to leave Arabic behind, thinking it would only hold us back. That was the logic of the times (along with Westernizing names, which comes up in the novel). When I moved to Quebec, French was a politicized and exclusive language, a function of laws and nationalist aspirations, and I never felt I belonged fully in that world. Later on, as an adult, I began to look at French differently, and the ability to translate from French to English played a large part in making me feel useful here. As a result of all these circumstances, I think and dream and write in English.

12. Hotline is now coming out in the United States, almost two years after its release and subsequent great success in Canada. What can you say to your new American readers about how Hotline portrays the immigrant experience in Quebec?

Hotline may use the specific circumstances of leaving behind the Arab world in the 80s on account of a civil war, and moving to the French-speaking part of North America which had its own unique nationalist aspirations. But its universal resonance and the reason why it has found so many readers comes more from the fact that we all live through major transitions at some point on our lives, changes that will traumatize us and test our will and fundamentally evolve and break us, and the story of how we make it through to this other side of ourselves is what ultimately makes our journeys meaningful.

Of the several major transformations I’ve experienced along the way, I’ve always found that the first year is the most challenging. Everything happens for the first time, and there are no clearly defined guidelines. And then seasons change, we see the journey in all its permutations, and the second year brings with it a sense of stability. We’ve done this before, we have a basis to believe in what’s possible. Whether it’s immigration or divorce or death or new life, we will all go through that journey of a first year.

If Muna connects to readers, it’s because she’s open and honest about those first twelve months. My hope is that American readers will read past the specifics that make up her immigration, and invest in the larger journey of personal transformation here that connects us all.

Dimitri Nasrallah is the author of four novels, including Hotline, a Canadian bestseller that was long-listed for the 2022 Giller Prize and was a 2023 finalist for Canada Reads. Nasrallah was born in Lebanon in 1977, during the country’s civil war, and moved to Canada in 1988. His previous books include The Bleeds (2018); Niko (2011), which won the Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction; and Blackbodying (2005), which won Quebec’s McAuslan First Book Prize. His books have also been nominated for the Dublin Literary Award and the Grand Prix du Livre de Montréal. Nasrallah lives in Montreal, where he is the editor of Esplanade Books and teaches creative writing at Concordia University.

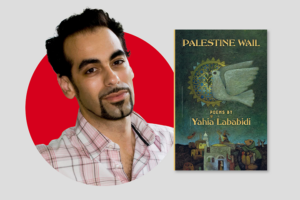

Yahia Lababidi | The PEN Ten Interview

When we refuse to acknowledge the suffering of others, and the role we play in it, we contribute to our own suffering, since we are One. The violence we commit throughout the world or allow to take place in our name is like a karmic serpent that will find its way home, to our doorstop.

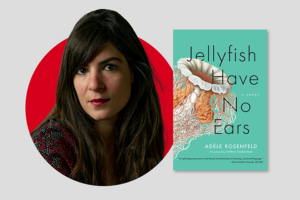

Adèle Rosenfeld | The PEN Ten Interview

An altered perception of sound results, oddly enough, in a sharper focus on sound and a more emotional relationship with hearing. The loss is overpowering, the obsession with hearing is outsize.

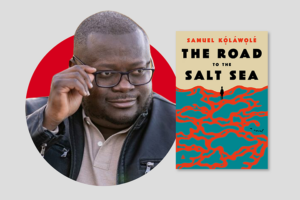

Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé | The PEN Ten Interview

As authors, we create something we hope will be beautiful out of nothing. The outcome of our hard work is never guaranteed.

Dalal Mawad | The PEN Ten Interview

Women are survivors and victims, they bear a large brunt of Lebanon’s protracted violence and crises, but they are also changemakers, mediators, powerful actors and storytellers and so I wanted them to own their narrative.