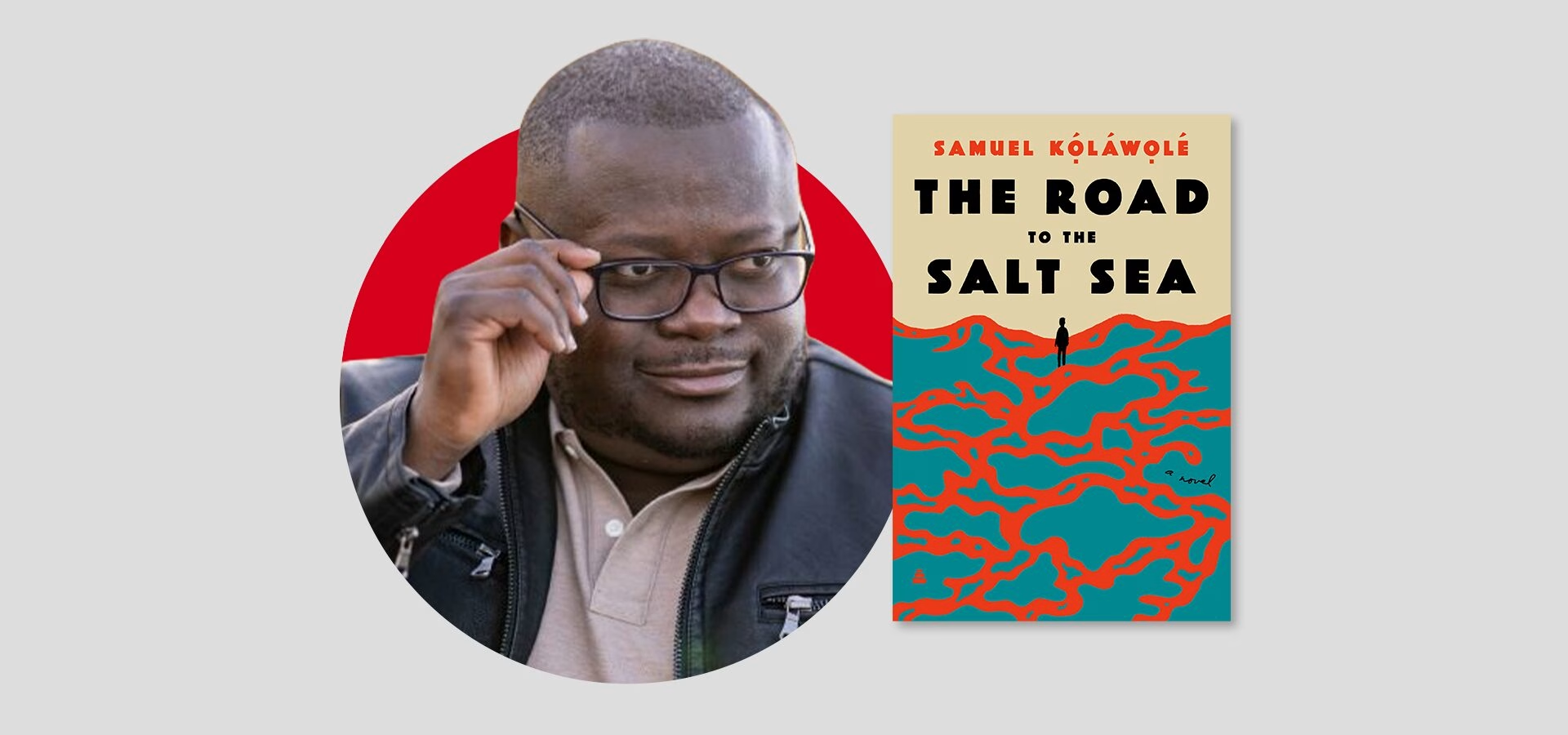

Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé | The PEN Ten Interview

August 1, 2024

A beautifully brutal and vivid novel, The Road to the Salt Sea (Amistad, 2024) is Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé‘s heartbreaking story of Able God–a low wage worker at a four-star hotel who gets wrapped up in a treacherous journey. Trying to save himself, Able encounters a group of migrants who attempt to make it to Europe but fall prey to traffickers, starvation, and life-threatening traumas.

In conversation with PEN America Senior Accountant Andre Booker for this week’s PEN Ten, Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé shares insights into his writing process, the cultural influences behind The Road to the Salt Sea, and where he believes resilience comes from. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

1. Congratulations on the release of your novel! What inspired you to write The Road to the Salt Sea? Was there a particular moment or experience that sparked the idea?

Many years ago, I took part in an artistic road trip with a group of authors and photographers. We visited three nations in West Africa to showcase our work and establish connections with local artistic communities. During one of our stops in Accra, Ghana, I met a group of migrants who had made a risky journey over the Sahara and had been deported. Their stories haunted me for months until I decided to write a short story. It was published by the prestigious literary journal AGNI under the title “Sweet Sweet Strawberry Taste.” Surprisingly, the story resonated with readers, and I recognized that it had the potential to be expanded into a novel.

2. What is your creative process? Do you have any unique ways/habits to get in the zone?

I have this weird habit of getting up early in the morning to write. The greatest time to write, in my opinion, is between three and seven in the morning when everything is quiet and your mind isn’t yet overtaken by the problems of the day. (Do what works for you.) I haven’t been writing much lately, but I still wake up around those hours. When I do, I sometimes do something else. Thinking and observing is also part of my process. Before they are turned into fiction, my ideas go through a protracted gestation stage. Making excursions to bookstores also inspires me. There’s something special about seeing or smelling the finished copy of a book.

“We are a nation of dreamers, which may sometimes create a very competitive and hostile environment where the end justifies the means, but it is also what makes Nigerians some of the most successful individuals in the world today.“

3. Can you describe the cultural influences that shaped the narrative of your book?

I started my literary education by reading works by Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley, Zora Neale Hurston, Shirley Jackson, and James Baldwin, Henry James, Jack London, Charlotte Bonte, and Ernest Hemingway, to name a few. I also loved Stephen King’s writing. After that, I was introduced to the African Writers Series, published by Heineman, which had a profound influence on me and shaped me into the writer I am now. Therefore, works that interrogate issues of gender and class injustice, as well as those that depict the macabre and spooky aspects of life, shaped my literary sensibility. I also drew on my experiences living and growing up in Nigeria’s social and political climate.

4. What message or emotion do you think readers will take away from Able God’s experience witnessing the hotel murder? Do you think sexism or classism will impact the reader’s opinion on the characters?

I wrote the first part of The Road to the Salt Sea with elements of thriller in mind, so the hotel murder serves as a watershed moment for the protagonist. Able God’s life is forever changed after that. The victim, Dr. Badero, is affluent, powerful, and abusive. Able God, a man down on his luck, works to serve people like Dr Badero at the hotel, so the hotel scenes in the story, like other parts of the novel, highlight social class disparities. The misogyny is far worse. My work interrogates social class and gender privilege as intertwined, even inextricable, especially in Africa. I want readers to come away from my novel feeling that my characters are real, even if they are sometimes unlikeable or flawed.

5. I don’t think many people from first-world countries can truly put themselves in Able God’s shoes. What would you say about Able God’s resiliency? Where does it come from?

I think his resilience comes from a history filled primarily with hardships. When all you’ve ever done is strive for what you want, that becomes your posture in life. Many people believe that in Nigeria, you either have to control your own fate or become a victim of your environment, thus you must have the willpower to persevere through difficult times. It’s a case of the strongest surviving. Even when you don’t succeed, you keep trying. Furthermore, religion instills in Nigerians the optimism that no matter how horrible the past was, the future will be better. We are a nation of dreamers, which may sometimes create a very competitive and hostile environment where the end justifies the means, but it is also what makes Nigerians some of the most successful individuals in the world today.

“I enjoy giving my characters names that make them stand out. I wanted to reflect the modern Nigerian custom of giving newborns names of that appear arbitrary but are actually meaningful upon deeper inspection. It was also my way of relinquishing control and allowing them to be themselves on the page.“

6. Chapter 16 is brief but brimming with anxiety as Able God finds himself at the Nigeria-Niger border. Do you believe an audiobook can evoke the same tension in this scene as reading the chapter would? How do you think audiobooks have changed your profession?

Some say that listening is an inferior form of engagement because those who listen to books recall less than those who read them. I disagree. As simple as it is to multitask with audiobooks, the format makes it more difficult to return to the place where your attention wandered. But I think audiobooks elevate the reading experience beyond the text. Atta Otigba was an excellent narrator for The Road to the Salt Sea and a great match. Atta’s deep voice perfectly captured the rhythm of my work, and he brought an amazing energy to the dialogue. Listening to the audiobook of my novel was a surreal experience. It was almost as if I hadn’t written the book, as if I were peering in from outside. Chapter 16 was no exception. The narrator made it even better.

7. Names such as “Able God,” “Ghaddafi,” “Dr. Badero,” “Abdulrazak,” and “Ben Ten” can be quite captivating. How does a character’s name impact their persona and vice versa?

I enjoy giving my characters names that make them stand out. I wanted to reflect the modern Nigerian custom of giving newborns names of that appear arbitrary but are actually meaningful upon deeper inspection. It was also my way of relinquishing control and allowing them to be themselves on the page. The novel’s earlier incarnation had a different name. Once I renamed it Able God, I saw that it related to one of the main themes of the book. I suppose that’s part of the magic that happens while writing fiction.

8. Does character development become easier with more writing experience? Have any parts of Able God’s story shown up in your previous work?

It does, in some ways because more writing experience makes you a more skilled practitioner of the craft of fiction writing. In other aspects, no, because each character is unique, and you learn more about them as the story progresses. Sometimes you think you know your characters and you try to control them, but they show you they can’t be controlled. “Sweet Sweet Strawberry Taste,” written in first person plural, grew into The Road to the Salt Sea. To make it into a novel, I had to change the narrative from a collective voice to the third point of view; Able God came out of that process. Able God was a new creation. Perhaps he might reappear somewhere down the road.

9. How crucial is it to be descriptive in order to make the most out of a pivotal moment in your book?

Very crucial. You want to draw the reader in; it’s like inviting them into your most intimate moments. It’s like saying to the reader “slow down, pay attention.” You don’t want to draw too much attention to it, but you want it to be enough to show its importance. Nothing beats offering an immersive experience to the reader when the story requires it the most.

“The whole creative process, in my opinion, is an exercise in taking chances. As authors, we create something we hope will be beautiful out of nothing. The outcome of our hard work is never guaranteed.“

10. I find that many of your chapter opening sentences are thought-provoking and attention-grabbing. In particular, the beginning of Chapter 11 made me reflect on the nature of risks. How do you perceive risks in the context of artistic expression, writing, and bringing ideas to life?

The whole creative process, in my opinion, is an exercise in taking chances. As authors, we create something we hope will be beautiful out of nothing. The outcome of our hard work is never guaranteed. There are many unknowns at every stage of the process, from creation to getting the book into the reader’s hands. Therefore, to be a great artist, one must be a dreamer and a believer. You must also be ready to fail.

11. I really liked Ben Ten’s words: “There can be no success without risking something.” Do you have any advice for those who allow fear to stand in the way of their dreams?

You don’t know what’s on the other side of your fears. Maybe it’s the fulfillment of your long-awaited dreams. Go for it!

12. Of all the talented Nigerian creatives, are there any you would like to give a shoutout to? What’s notable about their work?

Poets like Romeo Oriogun, Gbenga Adesina, Saddiq Dzukogi, and Damilola Aderibigbe, as well as fiction writers like Tochi Eze, Uche Okonkwo, and Pemi Aguda, to name a few, give me hope for the future of Nigerian literature. And of course, Atta Otigba. The works of these writers reflect a diverse range of styles, genres, and subjects. They are bold and refuse to be pigeonholed.

13. What would be a one sentence summary for your novel, The Road to the Salt Sea?

Able God works at a high-end hotel in Nigeria, but an incident sends him fleeing into the desert with a gang of drug-addled migrants.

Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé was born and raised in Ibadan, Nigeria. He is the author of a new, critically acclaimed novel, The Road to the Salt Sea. His work has appeared in AGNI, Georgia Review, The Hopkins Review, Gulf Coast, Washington Square Review, Harvard Review, Image Journal, and other literary publications. He has received numerous residencies and fellowships, and has been a finalist for the Graywolf Press Africa Prize, shortlisted for UK’s The First Novel Prize, and won an Editor-Writer Mentorship Program for Diverse Writers. He studied at the University of Ibadan and holds a Master of Arts degree in Creative Writing with distinction from Rhodes University, South Africa; is a graduate of the MFA in Writing and Publishing at Vermont College of Fine Arts; and earned his PhD in English and Creative Writing from Georgia State University. He has taught creative writing in Africa, Sweden, and the United States, and currently teaches fiction writing as an Assistant Professor of English and African Studies at Pennsylvania State University.

Dalal Mawad | The PEN Ten Interview

Women are survivors and victims, they bear a large brunt of Lebanon’s protracted violence and crises, but they are also changemakers, mediators, powerful actors and storytellers and so I wanted them to own their narrative.

Marcela Fuentes | The PEN Ten Interview

For Pilar, her anxieties and insecurities solidify into this belief that she has been cursed. She accepts it as true, and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.

Matthew Mendoza | The PEN Ten Interview

Place and story are important to me. The best work exists where the amazing and magical meet the sinister.

Parul Kapur | The PEN Ten Interview

There is always a cost to defiance. The question is whether you can bear it or how you can transcend it.