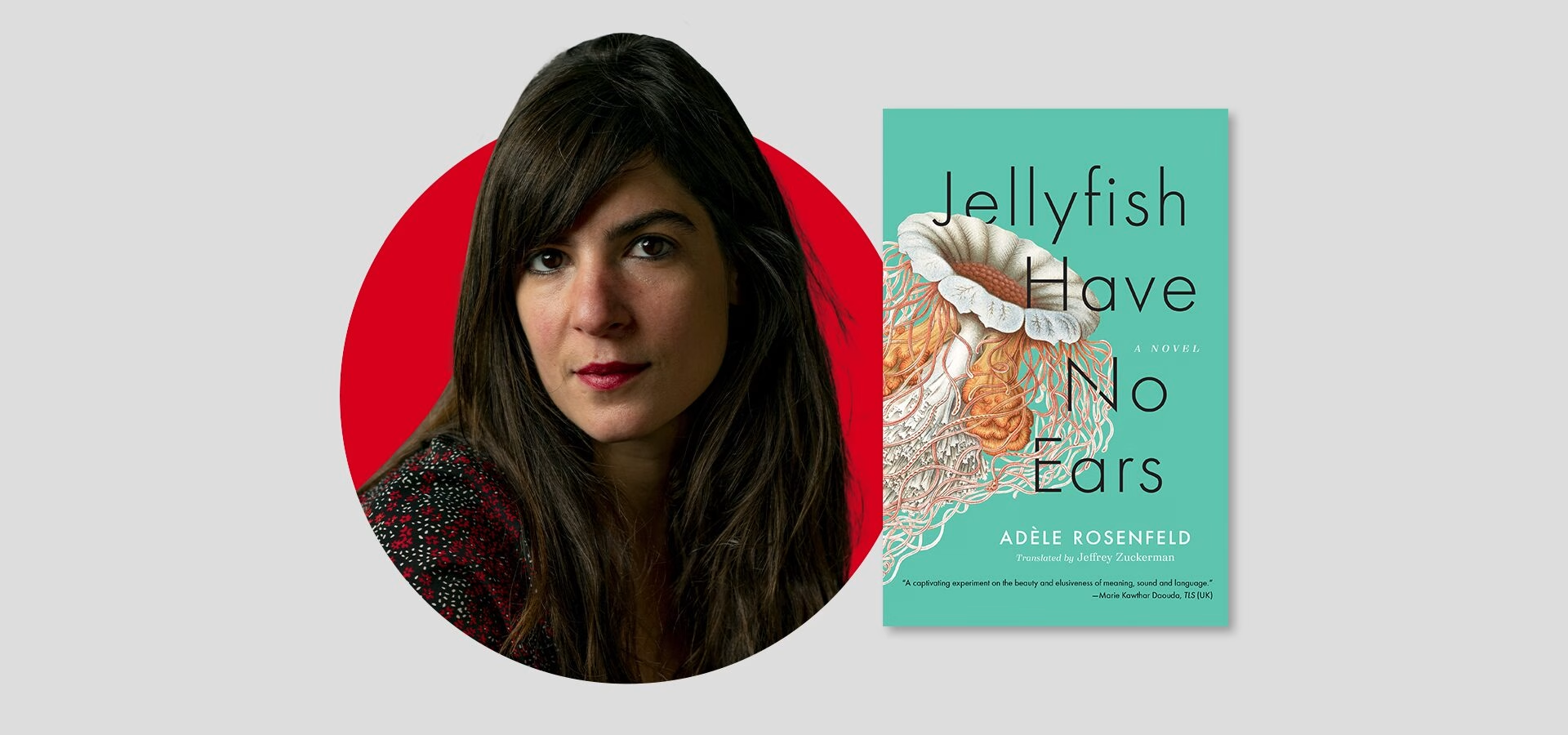

Adèle Rosenfeld | The PEN Ten Interview

August 7, 2024

Adèle Rosenfeld’s debut novel Jellyfish Have No Ears (Graywolf, 2024), translated from French to English by Jeffrey Zuckerman, is a colorfully sonorous story with surreal details. As the reader follows protagonist Louise grappling with the decision of whether or not to get a cochlear implant, they are brought into a world that is challenging, imaginative, and filled with love. Through Louise’s professional life as a Town Hall employee to her personal life with friends, family, and lovers, Jellyfish Have No Ears intimately invites readers to explore what it’s like to live with a hearing impairment.

In conversation with World Voices Festival & Literary Programs Coordinator, Sarah Dillard, Adèle Rosenfeld shares what she believes we can learn from animals, defines onomatopoeia, and describes what she believes encompasses our identity. The English portion of the interview was kindly translated by the books’ translator, Jeffrey Zuckerman. (Bookshop and Barnes & Noble)

August 15, 2024 Editor’s note: This interview has been updated with newly translated answers in English by the translator of Jellyfish Have No Ears, Jeffrey Zuckerman. Translation was provided as a courtesy by the translator to the publisher, Graywolf Press. An earlier edition of this interview was amended to include proper citation of Jeffrey Zuckerman as the novel’s translator.

1. Congratulations on your debut novel! Where did Jellyfish Have No Ears start? Was it a short story that grew into a novel or was it always meant to be a longer piece?

Coming to write on this essential subject wasn’t something I imagined; deafness as a subject imposed itself on me. As such, for quite some time, I only wrote short stories on that theme, such as the science-fiction piece “The Hearing-Aid Brigade,” forthcoming from Words without Borders. And then, one day, while I was in a hospital waiting room for a doctor’s appointment, I wrote the first chapter of Jellyfish Have No Ears. From the outset, I knew it would be a novel. All the throughlines of the text were there; the voice was there.

2. There are such vivid and detailed descriptions of sound throughout the book. How has your own hearing impacted your relationship to sound?

An altered perception of sound results, oddly enough, in a sharper focus on sound and a more emotional relationship with hearing. The loss is overpowering, the obsession with hearing is outsize. Putting hearing into words has allowed me to hear better, to commit sounds to memory the better to hear them.

Étrangement, une perception altérée du son entraîne une attention encore plus fine au son et un rapport affectif à l’ouïe. Le manque est si fort, l’obsession de l’écoute, si importante. Mettre des mots sur l’écoute m’a permis d’entendre mieux, de mémoriser les sons pour mieux les entendre.

“An altered perception of sound results, oddly enough, in a sharper focus on sound and a more emotional relationship with hearing. The loss is overpowering, the obsession with hearing is outsize.“

3. Animals show up throughout the novel and even hold a place in the title. What do you think humans can learn from animals?

Animals’ sensory systems: their understanding comes through their senses, as a matter of survival, of reading the world around them. When one sense is gone, humans can redistribute that acuity across their other senses. Animals make it possible for us to take a different tack in our approach to a situation, and this different tack, for humans, amounts to abandoning a standard premise, trusting in other capabilities, changing perspective, considering it from another angle. Maybe that’s what we can learn from animals: to decenter ourselves in order to get around obstacles.

Le système sensible des animaux, leur compréhension passe par les sens, c’est une question de survie, de lecture du monde. La déficience d’un sens permet de déployer chez l’homme cette acuité primaire aux sens. Les animaux peuvent nous permettre de faire un pas de côté dans notre appréhension d’une situation, et ce pas de côté, chez l’homme, signifie quitter un système, normé, s’en remettre à d’autres capacités, à changer un point de vue, à aborder sous un autre angle. C’est peut-être ça qu’on peut apprendre des animaux, à se décentrer pour contourner des obstacles.

4. In chapter 9, Louise mentions shaving her head so people can see her hearing aid and know that she has a disability. How do novels help reveal the invisible?

Literature is a space in which we can willingly enter someone else’s interiority. It’s a place of peaceful meeting, as nobody will force us to read the book we hold in our hands, which provides a special premise for discovering difference. The act of reading creates an especially singular, intimate relationship, a relationship woven in silence. And the unconstrained form of a novel allows us to explore the possible, the complicated, the paradoxes that make it possible for us to get closer to reality.

La littérature est l’endroit où nous pouvons accéder à une intériorité autre, de notre plein gré. C’est un lieu de rencontre pacifique, puisque personne ne nous obligera à lire le livre que nous avons entre les mains, ce qui crée des dispositions exceptionnelles pour découvrir une altérité. Il y a dans l’action de lire un rapport si singulier, intime, qui se tisse dans le silence. Et le roman dans sa forme libre permet d’explorer le champ des possibles et d’explorer la complexité, les paradoxes qui nous permettent d’approcher plus finement la réalité.

5. You describe how the sounds from the words jour and nuit don’t align with their meaning. Are there ever moments when sound and sense align? If so, do these moments transcend differently than the others?

Close attention to sound is a matter of language, too. The experience of a hearing loss that warps language is an opportunity for the narrator to explore language’s asymmetries and discrepancies; it’s a linguistic deep-dive! And she takes some comfort from this: she may be at a remove, and, sometimes, so is language.

With the “sound herbarium,” which is a poetic way of translating particular sounds, she brings sound and poetic image into alignment with meaning.

Onomatopoeia is a space where language or sound and sense align. Poetry tries to align sound and image, which is what I was playing with for the “sound herbarium” by making the word and the idea reverberate so that the narrator could recall the acoustic effect.

L’extrême attention portée au son est aussi une affaire de langage. L’expérience d’une déficience sonore qui déforme le langage est l’occasion pour la narratrice d’explorer les dissymétries de la langue, ses incohérences, c’est une plongée linguistique ! Elle en tire un certain réconfort, si elle est décalée, la langue l’est aussi parfois !

Avec « l’herbier sonore », qui est un moyen poétique de traduire certains sons, elle fait coïncider le son et l’image poétique avec le sens.

Les onomatopées sont des endroits de langage ou son et sens coïncident. La poésie tente de faire coïncider son et image, c’est ce avec quoi j’ai joué pour « l’herbier sonore » en de faire sonner le mot et l’idée pour que la narratrice se souvienne de l’effet auditif.

“The experience of a hearing loss that warps language is an opportunity for the narrator to explore language’s asymmetries and discrepancies; it’s a linguistic deep-dive! And she takes some comfort from this: she may be at a remove, and, sometimes, so is language.“

6. The Soldier, Cirrus, and the Botanist change over time in a way that reflects Louise’s character development, hearing loss, and decision-making process. What was your intention? What role do they play in Louise’s life?

Each character symbolizes one of the narrator’s emotional states: the dog represents her anger, the soldier the war between the deaf and the hearing as well as the struggle to keep going, and the botanist the archive of lost sounds and the imagination needed to fill these gaps. But these imaginary travel companions also hem in the narrator, serving their own ends and isolating her from reality. I wanted to orchestrate this tension between reality and imagination all the way to Louise’s final decision.

Chacun des personnages symbolise un état émotionnel de la narratrice, le chien représente la rage, le soldat la guerre entre la sourde et l’entendante et la lutte pour tenir et la botaniste l’archive des sons disparus et l’imagination pour combler ces vides. Mais ces compagnons de route imaginaires enferment aussi la narratrice, fonctionnent pour leur propre compte et l’isolent de la réalité. C’est cette mise en tension entre réalité et imagination que j’ai voulu mettre en scène, jusqu’à la décision finale.

7. Many of the people in Louise’s life have a strong opinion on whether or not she should get an implant and deprive her of the opportunity to self-determine such a life-changing decision. In several cases, these characters talk about the impact on their own lives instead of prioritizing Louise’s needs. However, Louise loves them all nonetheless. How have the allies in your life been? Who has been the most supportive?

We always know better than others what we’d do in their place! That’s what I got a kick out of with staging all this.

I don’t have a cochlear implant. This novel is just that: a novel. Not a memoir. The narrator is a fictional character and I needed this fictional counterpart to widen the range of possibilities, to evolve just as she had on these questions, to share them. I had her live out one of my possibilities. As Kundera said: “A novel examines not reality but existence. And existence is not what has occurred, existence is the realm of human possibilities, everything that man can become, everything he’s capable of.” That’s what I’ve tried to do with this novel: explore one of my futures, or a present possibility in order to master these questions.

On sait toujours mieux que les autres ce qu’on ferait à leur place ! C’est ce qui m’a amusée de mettre en scène.

Je n’ai pas d’implant. Ce roman est justement un roman, ce n’est pas un témoignage, la narratrice est un personnage fictif et j’ai eu besoin de ce double fictif pour ouvrir le champ des possibles, évoluer avec elle sur ces questions, les partager. Je lui ai fais vivre un de mes possibles. Comme le disait Kundera : « Le roman n’examine pas la réalité mais l’existence. Et l’existence n’est pas ce qui s’est passé, l’existence est le champ des possibilités humaines, tout ce que l’homme peut devenir, tout ce dont il est capable. » C’est ce que j’ai tenté de faire avec ce roman, explorer un de mes futurs, ou une possibilité présente pour apprivoiser ces questions.

8. In chapter 31, Anna says; “If you lose something, you haven’t had anything subtracted from your being.” What encompasses our “being”?

Anna is saying that when something is lost—in this case, a sense—nothing is taken from the person’s essence. What matters is thinking carefully about this notion of identity: her disability is not her identity. It’s part of her, but she can’t be reduced to this loss. As Louise goes through an identity crisis, experiencing life solely through this loss that becomes an obsession with loss, sense, and language, she tries to fill it however she can, and therefore through imagination. Anna is trying to move the stakes of identity so as not to lose Louise. No matter what happens, even if she drains her ability to adapt, nothing can change her.

Ce que veut dire Anna, c’est que la perte de quelque chose, ici un sens, n’enlève rien à l’essence de l’être. Il s’agit de faire attention à cette notion d’identité, sa déficience n’est pas son identité, ça fait partie d’elle, mais elle n’est pas réductible à cette perte, alors que Louise traverse une crise identitaire, ne vit qu’à travers cette perte, qui devient une obsession de la perte, du sens et du langage et cherche à combler par tous les moyens (et donc par l’imagination), Anna cherche à décentrer l’enjeu de l’identité pour ne pas perdre Louise. Quoi qu’il lui arrive, même si elle épuise ses capacités d’adaptation, rien ne pourra l’altérer.

9. What mythological history would you create for the deaf and hard of hearing? What role would they play in a founding myth of mankind?

The deaf person, seeing that there weren’t myths around the deaf, that all the myths about disability were about the blind, whose language is distorted, cannot hear the language of God (“in the beginning was the Word”—in French, verbe means “spoken word”) and so is exiled from myth. In this context, in the jellyfish, I saw the Oedipus myth anew, because in reality, it’s not about eyes but about ears: he misheard the oracle, misinterpreted him.

The hard-of-hearing and the deaf restore communication where it belongs, specifically because it’s about actually listening, not a distracted ear.

Constatant qu’il n’y avait pas de mythes autour des sourds, que la place était réservée aux aveugles, le sourd, dont le langage est altéré, ne peut entendre la langue de dieu (« au commencement était le verbe »), et donc est banni des mythes. Dans cette perspective, dans les méduses, j’ai revu le mythe d’Œdipe car en réalité, ce n’est pas une affaire de vue mais d’oreilles, il a mal entendu l’oracle, l’a mal interprété.

Les malentendants et les sourds remettent la communication à sa place, justement parce qu’il s’agit d’écouter véritablement, non pas d’une oreille distraite.

“I don’t have a cochlear implant. This novel is just that: a novel. Not a memoir. The narrator is a fictional character and I needed this fictional counterpart to widen the range of possibilities, to evolve just as she had on these questions, to share them. I had her live out one of my possibilities.“

10. What do you hope people gain from reading Jellyfish Have No Ears?

When I was writing Jellyfish Have No Ears, a friend asked me if I was writing a political book. Was it a book against the hearing? The question really helped me to pinpoint the tone: I didn’t want to write a screed, even if there are spots in the text where I had to describe scenes in an ironic manner—the consternation of institutions and businesses at those who don’t fit neatly in boxes, and who don’t stay put. That’s what I was showing in the narrator’s work life at the municipal office where the more disabled she became, the more she was demoted: it was another way to speak out against the phenomenon of HR repeatedly “reassigning” employees whose invisible disabilities are misunderstood and progressive.

This book is another perspective on difference, a deep dive into otherness, a refusal to take stereotypes for granted.

Quand j’écrivais Les méduses n’ont pas d’oreilles, un ami m’a demandé si je faisais un livre politique. Est-ce qu’il s’agissait de faire un livre contre les entendants ? Cette question m’a beaucoup aidée pour trouver le ton de l’écriture, je ne voulais pas écrire un livre à charge, même s’il y a des endroits du texte où j’ai eu besoin de mettre en scène des situations de façon ironique, le désarroi des institutions/des entreprises face à des cas qui ne rentrent pas dans les cases habituelles, et qui évoluent. C’est ce que j’ai montré dans la vie professionnelle de la narratrice à la mairie où plus elle est handicapée plus elle est déclassée, autre manière de dénoncer les phénomènes de « placardisation » face à des employés dont les handicaps invisibles sont méconnus et évolutifs.

Un autre regard sur la différence, être plus attentif à l’altérité, à ne pas tenir pour acquis nos représentations.

Adèle Rosenfeld lives in Paris where she runs writing workshops. Jellyfish Have No Ears was a finalist for the 2023 Prix Goncourt for a first novel.

Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé | The PEN Ten Interview

As authors, we create something we hope will be beautiful out of nothing. The outcome of our hard work is never guaranteed.

Dalal Mawad | The PEN Ten Interview

Women are survivors and victims, they bear a large brunt of Lebanon’s protracted violence and crises, but they are also changemakers, mediators, powerful actors and storytellers and so I wanted them to own their narrative.

Marcela Fuentes | The PEN Ten Interview

For Pilar, her anxieties and insecurities solidify into this belief that she has been cursed. She accepts it as true, and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.

Matthew Mendoza | The PEN Ten Interview

Place and story are important to me. The best work exists where the amazing and magical meet the sinister.