The PEN Ten: An Interview with Darrel Alejandro Holnes

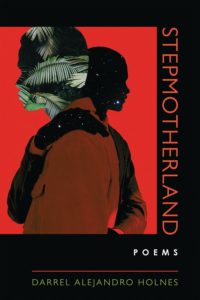

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Darrel Alejandro Holnes, author of Stepmotherland (Notre Dame Press, 2022) – Amazon, Bookshop.

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

1. What is the role of a writer in an era of social unrest? Polarization? Democracy in decline?

For many of us, writing is a means of surviving and working through the problems that come from social unrest. For others, writing in an era of social unrest is about empowering themselves and enacting change. And then there are those for whom it’s about speaking truth to power or documenting oppression. All of these intentions are important but I’d like to make room for writers who take breaks during eras of social unrest to focus on their family, health, or personal affairs such as immigration. There was a meme circulating on the internet at the top of the pandemic saying that Shakespeare wrote King Lear during a plague. I don’t know if that’s true, but I do know that being product-driven can lead to increased stress that can affect health and personal relationships, which can create huge obstacles to writing. I don’t think writers who take breaks should feel worthless or like they’re letting down “the revolution.” There will always be a revolution—show up for yourself during eras of social unrest and then show up for others through your writing.

2. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

I’ve always felt inspired by the mere fact that there are countless stories on every block in New York City, going back hundreds of years. This place has inspired me to keep writing because when I’m here/there I feel surrounded by fascinating characters, intriguing plots, complicated secrets, and passionate promises. It’s an incredibly giving place for writers, I think. There is inspiration everywhere. I tell my college students all the time that it’s such a privilege to be a young artist in a city that is as inspiring as this. But truly, wherever you are, you can make your city, town, suburb, or rural setting part of your writing process—inspiration can be everywhere for you too. Art is what you make of it. Consider this: each time you lift paint from the palette with your paintbrush make sure to refill the palette with more colors from the world around you. You’ll quickly realize just how rich that world, even if it’s not New York City, how rich that small town or big city world really is. It’s the same with language, you can pull from the world of images, sounds, and symbols physically around you when writing, even when writing about a far off or imagined place. Place can be a never-ending source for your creativity, it’s up to you to take advantage of what you’re given.

“We, as people, have more in common than we have that sets us apart. Pick up a book, make a friend with a stranger, however you can—connect, and you’ll see the proof is in the pudding—we are made to show compassion to one another, we are made to understand each other, we are made to connect.”

3. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

A few years ago I was consulting for nonprofits and I had the chance to work alongside staffers at the United Nations on various projects. From observing them, I learned the importance of precise language because in that setting you not only have to communicate to be immediately understood—you have to communicate to be translated. This is not dissimilar to how I grew up as a child surrounded by global politics and geopolitics, diplomacy, foreign aid and philanthropy, and international trade deals that happened in, around, or had a lot to do with the Panama Canal.

In my family, we speak Spanish, English, Spanglish, West Indian/Jamaican Patois, French creole/patois, French, and Panamanian slang. We code-switch constantly. And in Panama, there are others who speak Cantonese, our various indigenous languages, Arabic, Hebrew, Hindi, and many more. To believe that Standard American English or the Spanish of the Real Academia was better than the creoles, patois, or other colloquial blends would be to believe that my education in a U.S. or international school system made me somehow too good to converse with other members of my family and community-at-large, it would have put stones in my ears, and what a shame that would have been to miss out on their incredible ideas, meaningful stories, and the joy of long conversations with someone like my grandfather who told me stories while he fixed the radio on his kitchen table. I wouldn’t trade those memories for the world. All of these other languages help make me who I am today, help make my language what it is when I write. I try to learn new languages every day; I’m currently working on strengthening my French and have long added African American Vernacular Ebonics to my growing list of languages and lingos.

4. Why do you think people need stories?

People are stories. All a person is, is their memories, ones they share with others, ones they keep to themselves. Our personalities, our behavioral patterns, our ability to reason and form logic, how we use our motor skills, all of it is based on memory. And all memories are stories your brain has created to organize information it has stored using information it recorded when your past experiences were present ones. Right now, you, reading this, are making a memory. Maybe this is obvious to you or maybe this is confusing or a revelation, regardless, you will remember this—people are stories, not much more, not much less. And it’s a beautiful thing.

5. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Oh, so many. I’m re-reading Panamanian writers ranging from contemporary ones like Javier Alvarado and Cristina Henriquez to folks like Joaquin Cedeno, Cubena, and Gerardo Maloney. I’m a huge fan of Ingrid Rojas Contreras’ writing—super excited about her memoir coming out in July—Garth Greenwell, Ocean Vuong. Javier Zamora has a new memoir coming out, and of course, Rosebud Ben-Oni’s If This is The Age We End Discovery is game-changing. Lots of love to them all.

6. Stepmotherland, as well as your last collection, Migrant Psalms, give readers insight into Panamanian experiences of migration and pursuits of a new home. Though immigrants will certainly identify firsthand with the growing pains, transformative discoveries of self, and difficult losses that come with leaving their home country, many of your readers might not have these experiences. Why do you think it’s important for people to read narratives of migration, regardless of their citizenship history?

6. Stepmotherland, as well as your last collection, Migrant Psalms, give readers insight into Panamanian experiences of migration and pursuits of a new home. Though immigrants will certainly identify firsthand with the growing pains, transformative discoveries of self, and difficult losses that come with leaving their home country, many of your readers might not have these experiences. Why do you think it’s important for people to read narratives of migration, regardless of their citizenship history?

It’s simple. We, as people, have more in common than we have that sets us apart. Pick up a book, make a friend with a stranger, however you can—connect, and you’ll see the proof is in the pudding—we are made to show compassion to one another, we are made to understand each other, we are made to connect. Especially with travel being limited during the pandemic, all the more reason to go somewhere through great literature. It’ll remind you that all of the problems of today are manageable if we work together. It’ll give you hope that the pandemic will end soon. It’ll give you something to look forward to when the world is in a better place.

Narratives of migration are important because they remind us that national borders are in our heads. They remind us that at our core, everyone is striving for a better life, whether you do that by staying put and investing in your local community as we see in books that center being local, or if it is about personal growth and working on yourself as we often see in first-person, coming-of-age, character-driven literature, or if it’s in books like mine that tell stories of coming-of-age and coming out through a migratory experiences. They’re all connected; no matter the nation-state we were born in or want to be in, we’re all connected or want to connect.

7. In line with the previous question, is there a work of art (literary or not) that hinges on experiences altogether different from your own, that surprised you in teaching you something about yourself?

I’m reading The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts by Maxine Hong Kingston. It’s a Chinese American woman’s story of family secrets, Chinese mythology, and California life. I find the stories to be fascinating, poignant, and interesting. I’m excited to find ways of connecting with it despite many of the experiences in the book being outside of my own. The writing is strong; it was recommended to me by Ingrid Rojas Contreras, and I’ve been reading it in parts and find the stories to be both challenging and empowering. I highly recommend it to anyone looking to see life through a different lens.

8. In addition to writing, you are also a professor of dramatic writing at NYU. What is a lesson that you always make an effort to impart on to your students?

I was recently talking to them about how they shouldn’t base their self-worth as artists on the amount of followers they have online, how big of a payday they get for a project, or even how much good press they receive for their work. Social media has made everyone capable of becoming a celebrity. Although, as artists we engage in that marketplace to help promote our work, remember that the actual work is to make good art and good art comes when you make something that really matters to you and not exclusively when you are chasing a trend or a following, especially because you can’t always plan for trends. Make the work that makes a difference to you, and it will make a difference to someone else. And that person will always check out your next project because they’ll never forget how your previous work made them feel. That’s the best re-tweet or “like” that’s out there—that’s the cake, the rest is just frosting.

“Make the work that makes a difference to you, and it will make a difference to someone else.”

9. What are the connections between writing, performing, and teaching? Looking back, do you think you would’ve been surprised about the ways in which you’ve integrated your passions in storytelling, music, and education?

I come from a literary and performing arts community in Panama where everyone wears many hats. If you have an idea for a show you write it, and if you can’t find a director you direct it, and if you can’t find an actor you star in it. It’s not like there is an absence of talent in Panama, it’s just to say that come hell or high water, we get things done. If you really care about a project you find a way to work it out and give it your all and through that process you grow into different roles—producer, designer, publicist. That’s how I fell into taking on so many roles. I had an idea and I knew it was up to me to figure it out; it was only a matter of time before all of my skills and interests started to come together. Now I try to work from the intersection rather than stretch myself thin across multiple jobs. It’s a shift in mindset and has led me to be more productive while still finding time off to spend with family and friends.

My passion for education comes from my love of people and community. Civic engagement and responsibility is a major tenet in my family and the reason many of us enter public service or giving professions. I come from a family of nurses, doctors, teachers, professors, government officials, and politicians. They’ve always taught me that it’s important to work in service of the greater good of your community. That’s why I decided to name my short play commission, The Greater Good Commission because it’s part of my family legacy to center, celebrate, and support my community(ies), and it’s part of my cultural heritage to make it work no matter what.

The commission awards mini-grants to underrepresented Latine playwrights, the inaugural year focused on Afro/Black-Latine playwrights, the second year focused on LGBTQIA+ Latine playwrights; I can’t wait to announce what next year’s focus will be. The festival has especially become popular with college students seeking out new work by diverse playwrights with Latin American and Caribbean heritage. I’m thrilled that the plays we support can be a tool for their education as well as an excellent form of entertainment for all.

I’m excited that the commission and its accompanying virtual play festival contributes to the incredible tradition of great festivals produced by other artist-advocates that has made this city great, and that has made the digital space a safe space for innovation in arts as well as in education, especially during the pandemic. I see the digital space as one where people like me can continue to integrate and explore their passions.

10. Throughout Stepmotherland, there are so many images of hope among hardship. What is something that is providing you with hope today?

I search for hope every day. Sometimes I find it in my students and their excitement and interest in seeing a Broadway show for the first or the fortieth time. Sometimes I find it by flipping through old family photos in Panama. Sometimes I find it at an old friend’s birthday party in Brooklyn. Sometimes I find it over brunch with a new friend in Los Angeles. Sometimes I find it on Zoom with other Black queer writers. Sometimes I find it at an old college haunt in Houston with an old roommate. Or at a karaoke bar in Berlin singing in German for the first time.

Hope is important because it’s the seed of dreams and the antidote to despair. And there’s so much to despair over these days that finding and holding onto hope has become a full-time job. Nonetheless, I’m determined to keep dreaming and to, as Rev. Jesse Jackson once said, “keep hope alive.”

Darrel Alejandro Holnes is an Afro-Panamanian American writer. His plays have received productions or readings at the Kennedy Center for the Arts American College Theater Festival (KCACTF), The Brick Theater, Kitchen Theater Company, Pregones Theater/PRTT, Primary Stages, and elsewhere. He is a member of the Lincoln Center Director’s Lab, Civilians R&D Group, Page 73’s Interstate 73 Writers Workshop, and other groups. His play, Starry Night, was a finalist for the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center’s National Playwrights Conference and the Princess Grace Award in Playwriting. His play Bayano was also a finalist for the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center’s National Playwrights Conference. His most recent play, Black Feminist Video Game, was produced by The Civilians for 59E59, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Center Theater Group, and other theaters and venues. He is the founder of the Greater Good Commission and Festival, a festival of Latinx short plays.

Holnes is the author of Migrant Psalms (Northwestern University Press, 2021) and the forthcoming Stepmotherland (Notre Dame Press, 2022). He is the recipient of the Andres Montoya Poetry Prize from Letras Latinas, the Drinking Gourd Poetry Prize, and a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship in Creative Writing (Poetry). His poems have previously appeared in the American Poetry Review, Poetry, Callaloo, Best American Experimental Writing, and elsewhere. Holnes is a Cave Canem and CantoMundo fellow who has earned scholarships to the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Postgraduate Writers Conference at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and residencies nationwide, including a residency at MacDowell. His poem “Praise Song for My Mutilated World” won the C. P. Cavafy Poetry Prize from Poetry International. He is an assistant professor of English at Medgar Evers College, a senior college of the City University of New York (CUNY), where he teaches creative writing and playwriting, and a faculty member of the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University.