A responsive series from PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, featuring original creative reportage by incarcerated writers, accompanied by podcast interviews with criminal justice reform experts on the pandemic’s impact in United States’ prisons.

Volume 13.0 Table of Contents

- Introduction: Frances Keohane

- Temperature Check: An update on the state of vaccines in prisons

- Where are they now?: Catching up with some of our guests and writers featured in previous editions of Temperature Check

- Where are we now?: The latest developments in advocacy efforts and how you can get involved

Introduction To Volume 13.0:

The Closing Issue

At least 398,627 incarcerated men, women, and children infected.

Over 2,700 dead.

Though these numbers paint one devastating picture of the past 17 months, COVID’s impact behind bars endures beyond statistics. Fragments of the virus’s ruin live in the letters family members wrote when visitations ended; in thousands of compassionate release applications denied; in news articles, poems, and drawings from those on the inside detailing desperation for fresh air and human contact, toilet paper, and empathy. Fragments of ruin in empty promises of decarceration; in lockdowns and isolation, the psychological consequences of which will not be fully known for decades.

Fragments of ruin that threaded through the dispatches and interviews of this Temperature Check series. Closing our year-and-a-half rapid response newsletter, in this final issue, we check up on the people, organizations, and advocacy efforts featured in Temperature Check’s previous 12 installments. What changes have been brought about during this period of acute disaster? And what work still needs to be done? We hope that this issue serves not only as a reflection on the past 17 months, but also as a springboard for rebuilding a post-COVID world that embodies our values.

The much-desired return to a post-pandemic “normal” is now rattled by a new layer of consciousness about the many forms of injustice and inhumanity within the United States’ legal system. The notion of public safety, for example, has been blown open by the eruption of carceral facilities as viral hotspots. As COVID spread through jails, prisons, and detention centers, those on the outside wondered, should we include the health and well-being of incarcerated individuals in our definition of “public safety”? Do we have an ethical obligation to protect the most vulnerable, even if it means releasing them from prison and challenging our beliefs—be they grounded in data or not—about the threat of decarceration to public safety?

Though decarceration efforts were sorely lacking—of the 31,000 federally incarcerated individuals who sought compassionate release, for example, only 36 were approved by the Federal Bureau of Prisons—25,244 people have been released from prison to home confinement since the onset of the pandemic. Though sensationalized in the news media, in truth, only three individuals were on record for committing new crimes, one of which was violent.

These statistics pose a direct challenge to the fundamental assertion of the American prison system; they indicate that public safety and incarceration are not one and the same, and that releasing incarcerated people does not in itself pose a threat to the outside community.

Yet now, over 4,500 of the 25,000+ individuals released to home confinement—many of whom settled down, rebuilt ties with children and parents and spouses, found a new job or a house, received necessary medical treatment that they lacked in prison—are at risk of returning to prison. On January 15, 2021, the Trump administration issued a memo saying that those whose sentences lasted beyond the “pandemic emergency period” would have to go back. Despite his campaign promises to reduce the legal system’s footprint and recent urging from lawmakers and advocates across the political spectrum, President Biden and his legal team have maintained the ruling. Once the official state of emergency ends, there are two ways to prevent these individuals from returning to prison if the ruling holds: Congress could enact a law to expand the Justice Department’s power, allowing them to remain under home confinement; or Biden could use his clemency powers to commute the sentences.

Biden’s decision presents a critical junction, a nexus where incarceration’s status quo meets the possibility of reform. The opportunity at hand, informed by the past 17 months, is to create a new normal that elevates empathy and restoration, to choose an alternative to incarceration that strives for the safety of us all.

As we move beyond the pandemic, and beyond Temperature Check, we urge you to look to the injustices that the pandemic has uncovered about life behind bars—the inadequacy of prison health care, the failure of compassionate release, the challenges of an aging carceral population, and many more—as fuel for continued change.

Thank you for spending these 13 issues with us.

In gratitude,

Frances Keohane, 2020-2021 Fellow

PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Team

Caits Meissner, Director

Robert Pollock, Manager

Mery Concepción, Volunteer Coordinator

Frances Keohane, 2020-2021 Fellow

Mahima Akula, Summer 2021 Intern

Mely Kornfeld, Summer 2021 Intern

Seraphina Halpern, Summer 2021 Intern

Freedom Constellations is an interactive public art project that imagines a world where all youth have what they need to thrive and stay free. The banners, which can be seen from miles away, include an interactive augmented reality experience that illustrates a world where all youth are free in the clouds above city hall. The animation illustrates a collective poem co-created by youth organizers from RISE for Youth and Performing Statistics in Richmond, as well as dozens of youth organizers from across the country. View the full animation here. Photos by Mark Strandquist

Temperature Check An update on the state of vaccines in prisons

At the time we published Temperature Check Vol. 11, only 39 states included prisons in their vaccine rollout plan and only nine included them in phase 1. Now, as vaccines are widespread with abundant supply, only 49.3 percent of the United States is fully vaccinated. Public health officials are continuing to encourage people to get vaccinated as the delta variant surges around the globe—but what does this mean for incarcerated people, who have proven to be one of the most vulnerable groups to COVID-19?

- As of May 2021, 17 state prisons and the Federal Bureau of Prisons had vaccinated less than half of their prison populations, and as of April, 20 different states and the Federal Bureau of Prisons claimed that less than half of correctional staff had received their first dose. In Utah, South Carolina, and Alabama, less than 20 percent of the prison population has received their first shot—an undeniable repercussion from the fact that prisons and jails were not considered high-risk or prioritized for the vaccine. Some states have had more success, such as Rhode Island, where correctional staff went from cell to cell and asked residents if they wanted to get vaccinated; 73 percent of the incarcerated population is now vaccinated in Rhode Island.

- Multiple studies and surveys conducted by the CDC have demonstrated vaccine hesitancy among incarcerated people. As Belly of the Beast—a new and powerful film about forced sterilization in California women’s prisons—shows, the mistrust in prison medical services is rooted in real histories of abuse. Adding fuel to residents’ fear is the lack of accessible, accurate information they have about vaccines, and the growing number of correctional officers who are declining the vaccine.

- In Florida, an unofficial Facebook poll taken by correctional officers resulted in the majority of officers replying “hell no” to getting vaccinated. Unvaccinated prison staff pose a serious threat to residents, especially if incarcerated people are also not vaccinated. To learn more about the complicated relationship between incarcerated people and medical practitioners, the lack of information of vaccines, and why correctional officers refusing vaccinations is so dangerous, watch this episode of “Inside Story,” a new video series created by The Marshall Project for incarcerated people, and people on the outside, across the country.

These three pieces are from a larger series curated by Mahogany L. Browne, representing the new organization she helms as executive director, JustMedia, an open access, lens-based archive designed to assist and support advocacy efforts for systemic change through the art of storytelling. These works were also featured at Lincoln Center, as part of Browne’s groundbreaking role as poet-in-residence until the end of August 2021.

Where are they now?

Join us in celebrating some of the most exciting and life-shifting developments in the lives of our featured writers and guests:

- In Temperature Check Vol. 10, we talked with Ebony Underwood about how her father’s incarceration shaped her childhood and inspired her to found We Got Us Now, an organization supporting children and young adults with incarcerated parents. In March 2021, her father was released from prison. Celebrate this win by supporting We Got Us Now’s new campaign for accessible family visitation.

- Join us as we congratulate Vincent Schiraldi, an admirable and outstanding voice in the juvenile justice field, on his appointment to commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction. Revisit our conversation with Schiraldi from Temperature Check Vol. 4 to hear his vision for a community-based, restorative justice system.

- Lacino Darnell Hamilton, whose piece “Commitment To The Prison Movement Requires Belief In Incarcerated Citizens Capacity To Transform The World” partially appeared in Temperature Check Vol. 6 as an excerpt, was exonerated and released in September 2020. Read more about his wrongful conviction and incarceration.

- Juan Moreno Haines, whose reporting on the devastating COVID-19 outbreak at San Quentin State Prison was featured in Temperature Check Vol. 12, was awarded a 2021 Writing for Justice Fellowship. Haines will write a longform journalism piece analyzing San Quentin State Prison officials’ lack of adequate response to the coronavirus outbreak.

Where are we now?

What did the advocacy efforts we featured across Temperature Check accomplish, and where can your support still make a difference?

Legislative

- In Temperature Check Vol. 6, we spoke with Gloria J. Browne-Marshall about the racialized history of mass incarceration and the consequences of the 13th Amendment. This Juneteenth, U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and U.S. Representative Nikema Williams (D-GA) proposed an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would prohibit the use of slavery as punishment for a crime, undoing the loophole created by the 13th Amendment.

- The Less is More campaign: Community Supervision Revocation Reform Act (S.1144A / A.5576A), which we featured in Temperature Check Vol. 8 and which will restrict the use of reincarceration for technical violations of parole, was passed by the New York State Senate and Assembly in June 2021 and awaits signature into law. Contact Governor Andrew Cuomo to urge his action now!

- In Temperature Check Vol. 9, we covered felony disenfranchisement laws and the harms of prison gerrymandering. When the issue was published, only two states—Maine and Vermont—allowed incarcerated citizens to vote. Now, a nationwide movement has spurred many states to revisit their felony disenfranchisement laws. In the past five years, 13 states have overturned laws that prohibited people with felony convictions from voting. However, legal mechanisms do little to reflect realities; most people with felonies are unaware that they can now vote. Check your state’s ongoing efforts to restore voting rights through The Marshall Project and the National Conference of State Legislatures. Recent wins include:

- Proposition 17 in California was passed, restoring voting rights to over 50,000 Californians on parole for a felony conviction.

- Florida Senate Bill 7066 prohibited returning citizens from voting until they paid off all legal financial obligations imposed by a court before conviction. Twenty-three percent of the total debt still needs to be funded. Donate here to help fight the criminalization of poverty and restore voting rights to thousands of Floridians.

- On April 22, 2021, New York passed legislation that restored voting rights to people on parole.

- In Washington, effective January 1, 2022, 20,000 people will have their voting rights restored after a new law signed on April 7, 2021 automatically reinstated voting rights to people upon their release from prison.

- Following suit from Illinois, on May 27, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont passed a bill that ended prison gerrymandering. Connecticut is now the 11th state to abolish prison gerrymandering.

- In Temperature Check Vol. 10, Dunasha Payne and Ebony Underwood discussed the countless barriers that inhibit family relationships through the bars. In June, Connecticut became the first state to provide free phone calls to incarcerated people and their loved ones. Massachusetts may be the second—learn more about two recently introduced bills and lobby your representatives here and here. Federally, you can support the Martha Wright Act to limit the fees imposed on prison phone calls.

- In Temperature Check Vol. 10, Dunasha Payne also spoke about mothering while in prison. A congressional bill to improve health care for pregnant people and babies in custody passed in the U.S. House of Representatives last October. Contact your senator now to push it forward!

- Throughout the Temperature Check series, many people—incarcerated writers, family members, criminal justice experts—spoke about the harms of isolation in prison as it exists during and before the pandemic (the latter most often being in cases of solitary confinement). On April 1, Governor Cuomo signed into law the HALT Solitary Confinement Act, which restricts the prevalence and extent of solitary confinement in New York State correctional facilities.

organizational

- The Appeal, a leading source for news about the U.S. criminal legal system, closed in its original form in June. The Appeal Union seeks a worker-led relaunch and is accepting donations.

- The Marshall Project published their final report on the prevalence of COVID-19 in prisons in June, though updated data can be found at the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project. The Sentencing Project also covered the known cases of COVID-19 in juvenile facilities (last updated in May).

- Thanks to grassroots donations, the National Bail Out collective raised $1.2 million to #FreeBlackMamas, allowing them to liberate 80 Black mamas and caregivers. You can donate to National Bail Out and take other actions through their website.

- Die Jim Crow Records, the first record label for incarcerated musicians in America, raised $25,000 to distribute more than 30,000 masks to prisons across the country. They are now campaigning alongside the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers to donate music gear, including instruments, production equipment, and more to incarcerated musicians.

- Last June, we asked for your support in advocating for justice for Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and the countless others who have lost their lives to police violence and white supremacy. The petitions we shared then have collectively garnered more than 35 million signatures. Derek Chauvin was found guilty of all three charges he faced for his murder of George Floyd, legislation was introduced across the country to reallocate funds away from the police and ban no-knock warrants like the one executed by the police who murdered Breonna Taylor, and the Black Lives Matter movement sparked change globally. However, much remains to be done—continue to engage locally with demonstrations, and visit 5calls.org to make your voice heard.

- Campaign Zero, which advocates for the end of police violence in America, has introduced a new campaign, Nix the Six, to hold police unions accountable.

- On July 14, 2021, California Governor Gavin Newsom approved a state budget that included $7.5 million in reparations to survivors of state-sponsored forced sterilizations. You can continue to take action through actions listed in Belly of the Beast’s website.

- Freedom Reads: The Million Book Project has changed its name to Freedom Reads, and as of recently, shipped 13,425 books to readers in prison. You can learn more about opportunities to support their efforts through the organization’s website.

- Stay updated on what is happening behind bars across the country by subscribing to the Prison Journalism Project’s newsletter. Most recently, PJP curated a three-part piece with writers reacting to Derek Chauvin’s sentence.

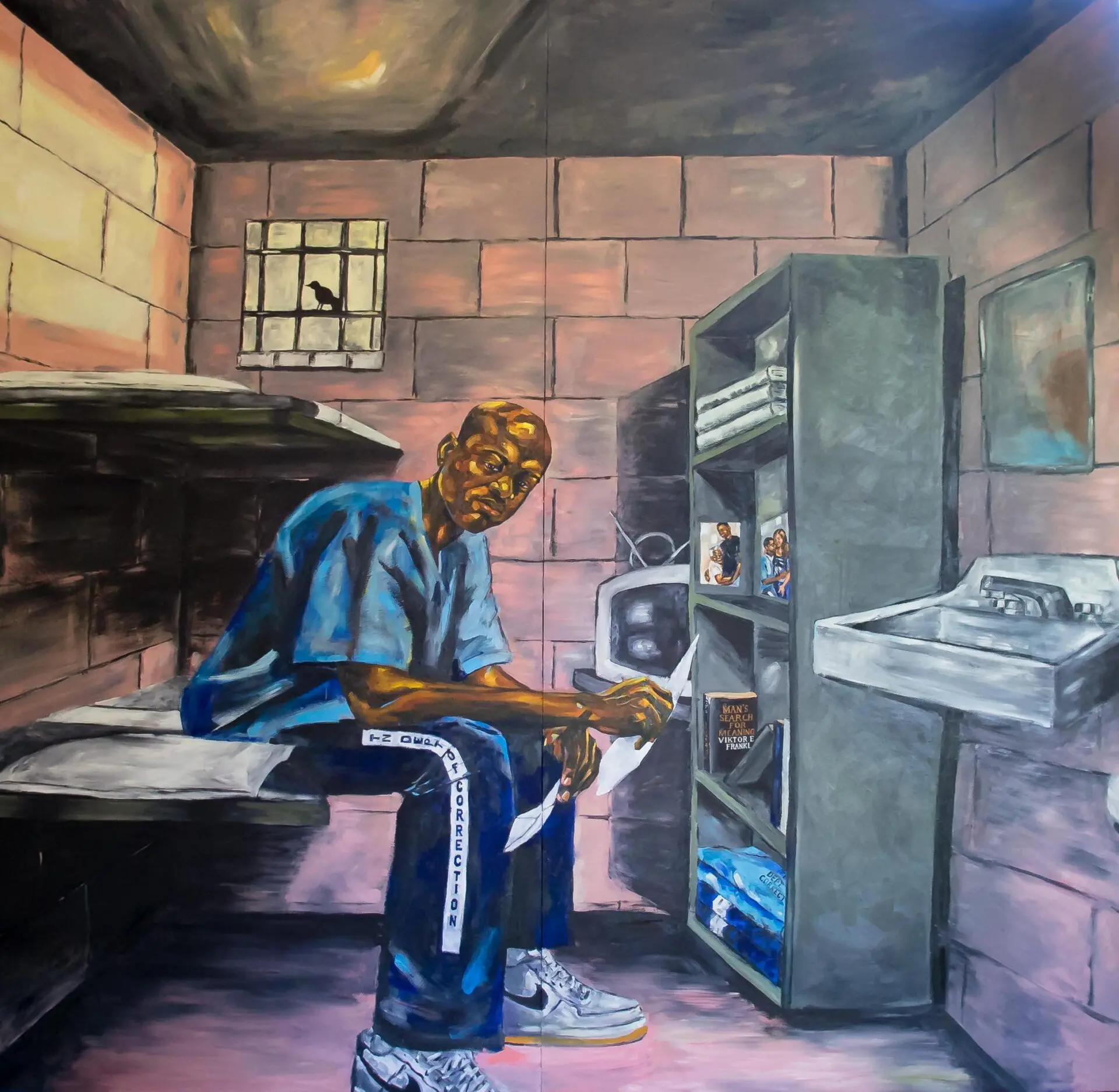

This selection of images are from the Time Saved vs. Time Served project. The original project, visioned by Tyra Patterson, who also serves as community outreach strategies specialist at the Ohio Justice & Policy Center, specifically highlights the uniforms women are forced to wear as a symbol for the many dehumanizing and unnecessary restrictions placed on women who are incarcerated. The multiple artists are all women who are directly impacted by incarceration. Patterson also shared her own piece as a reminder that “no matter where you are or no matter what you believe in, to always have hope, to bloom from the ashes, and always continue to shine.”