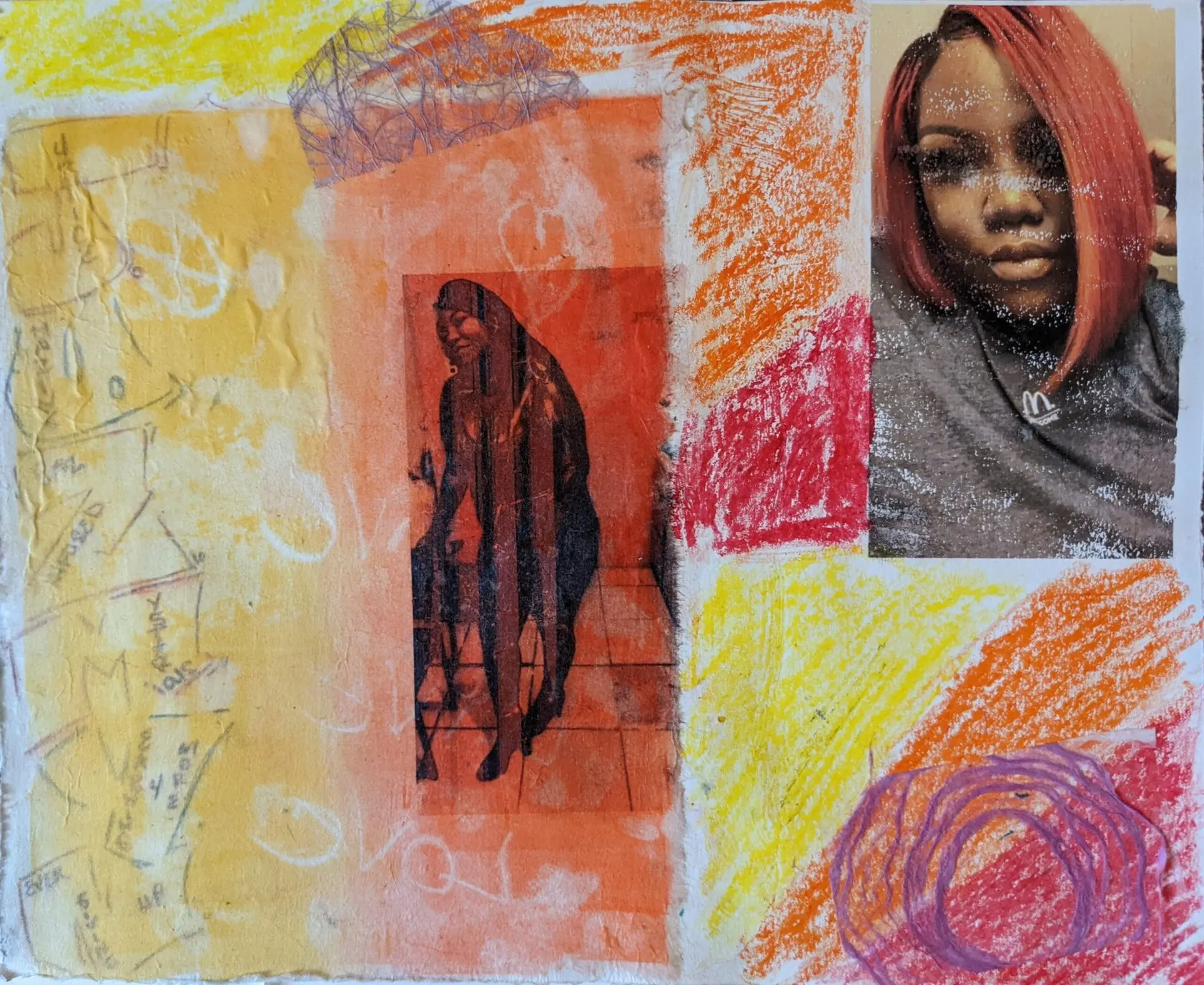

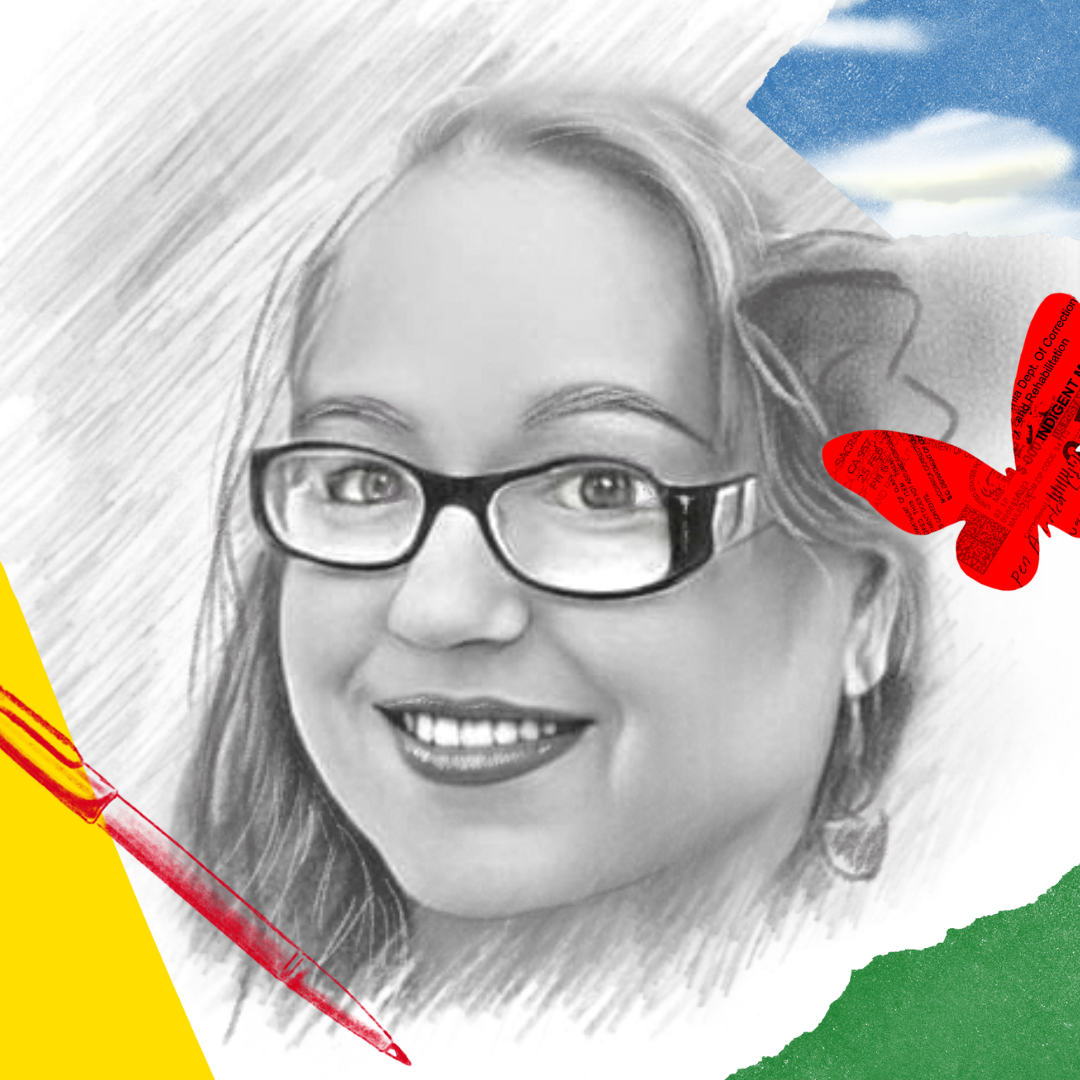

Earlier this year, Exchange for Change and O, Miami announced Catherine LaFleur as the 2023-2024 Luis Angel Hernandez Poet Laureate. Named for an incarcerated poet who passed away from cancer in 2018, the poet laureateship is an honorary two-year position awarded to an incarcerated poet within the Florida Department of Corrections. Past laureates include Echo Martinez (2019-2020) and Christopher Malec (2021-2023). Exchange for Change, a South Florida nonprofit offering educational and creative opportunities for incarcerated people, and O, Miami, a poetry nonprofit that produces several events and publications each year, hopes to create a model of communal learning about the experience of incarceration that encourages active advocacy for the educational and creative rights of people who live in jails and prisons.

Catherine LaFleur, based in Homestead, Florida, is the recipient of PEN America’s 2016 Prison Writing Contest Poetry Award and her work has appeared in several publications. During her tenure as Poet Laureate, LaFleur is expected to write occasional poems, promote the rehabilitative power of the arts, and help amplify the voices of other writers who are incarcerated. In this exclusive interview, Valentina Flores, editorial fellow for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, speaks with LaFleur about her time with Exchange for Change, how she came to write poetry, and what inspired some of her poems.

Congratulations on being named the 2023-2024 Luis Angel Hernandez Poet Laureate. Can you speak a little bit about what led you to participate in Exchange for Change?

Thank you. I have been with Exchange for Change since its inception. Exchange for Change was the first dedicated writing program to hook me. I joined Kathie Klarreich’s creative writing classes where poetry was always a component. We read Adrienne Rich, Maya Angelou, Robert Frost, and were encouraged to explore writing our own poetry. From that class, Exchange for Change has continued to bring local poets to teach seminars and introduce us to the poetry slam scene in South Florida.

What inspired you to start writing poetry? What is your history with the genre?

I think the story of the prison experience can get tangled in the sameness of our stories. All prisoners experience degradations, humiliations, and violations of the body. Eventually the details can become banal to readers. I fell into this trap myself from reading prisoner’s stories. Then I read work by Reginald Dwayne Betts. Poetry has a way of bypassing narrative. Instead of writing straight story about the women in solitary confinement here, through poetry I would write: “The anchorites with sighing songs/ are caught in jails within jails within jails/ the walls do pin their solitary bones/ and parchment wings upon pale white sheets/ punished for disobeying rules within rules within rules/ one for a cigarette, and two for soap, a third slave works much too slow.” Writing those words horrifies me in a way that using narrative about why solitary confinement is used abusively doesn’t. Poetry has the power to sharpen the focus of my words in a way that narrative can’t.

In your poem, “Gardener’s Memory,” which was awarded First Place in Poetry in PEN America’s 2016 Prison Writing Contest, you speak about your desire to resist being “tamed.” Can you speak about what being “tamed” means to you, and what led you to write the poem?

My parents had a vegetable garden. My chores included weeding and thinning plants growing astray. That garden looked so perfect. In exchange for harvest, a neighbor would keep up the garden when we went away on summer vacation. This always worked out well until the year my father planted a new variety of melon, a traveler. When we returned these vines had escaped under the back fence into our neighbors’ yards, even growing into our front yard and spilling into the street.

The prison I am in borders the Everglades and is lush with flowering plants and trees. There are very strict rules about what can be cultivated. Anything with thorns is banned, still we have a number of wild roses and other thorn bearing plants. These untamed ones grow and grow, the state is incapable of evicting them or keeping them outside the gates even though we are surrounded by fences and coiled razor wire. I remind myself to be that untamed beautiful growing thorny thing growing my way, beyond the confines of prison.

Your poem, “Resurrection City 2023,” ends by referencing “Resurrection City 1967,” which seems to invoke Martin Luther King, Jr.’s vision for the Poor People’s Campaign and the Resurrection City built following his assassination in 1968. Can you speak more about the historical parallel between Resurrection City 1967 and Resurrection City 2023? If there is a relationship between the two, what is the significance?

I was inspired to write “Resurrection City” because of my involvement in the Frederick Douglass Project, which seeks to change the public’s perception of the criminal justice system by becoming proximate with the humanity of incarcerated people. Much like the Poor People’s Campaign, prison reform is about human rights. Resurrection City gave us a humanized picture of who poor people are. The public was invited into this city to meet these people and find out what poverty looks like. I don’t think citizens on the outside know who the incarcerated are, they only see how prisoners are portrayed in sensationalized media outlets. The prison industrial complex has a vested economic interest in defining the incarcerated as those who should never be released from prison. We must change hearts and minds. How incredibly freeing it is to chat about the last book I read or movie I saw. The prison we are in fades as I listen to a visitor describe their vacation or the hot new restaurant they ate at last night. No matter where the conversation takes us, we are connecting beyond our labels of prisoner and free person. I invite every person reading this to investigate the Frederick Douglass Program. Perhaps you will choose to make a visit to your local Resurrection City.

What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Or, what’s a favorite poem you’ve written?

The most daring thing I have put into words are poems I have written about fellow inmates killed by corrections officers.

What’s the best advice someone has given you about writing poetry? What would be your number one piece of advice for someone who wants to start writing poetry but doesn’t know where to begin?

The best advice I received about writing poetry was to never rhyme anything! The first poem I made an attempt to write was drawn from a list of random nouns and adjectives my class threw into a pot. We each had to draw ten slips. Each line had to contain one of the words, each word could only be used once. This was a daunting writing exercise, but it allowed me to start by finally putting words to paper. Another piece of advice I will offer is, don’t be too serious! Remember, poetry, like writing, is a pleasure.

Note: PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program (PJW) finds it important to combat the erasure of the individual when considering language. As such, PJW rejects flattening state language such as inmate, convict, felon, or prisoner used to describe or refer to people who are incarcerated. Nevertheless, we are also committed to preserving the language incarcerated people choose to use in reference to themselves, their communities, and their experience with the carceral system

Catherine Lafleur is the 2023-2024 Luis Angel Hernandez Poet Laureate with Exchange for Change. Her work has been published in Cream City Review, The Voices Project, Scalawag, and PEN America: United We Stand. In 2016, she was awarded First Place in Poetry in PEN America’s 2016 Prison Writing Contest for her poem, “Gardener’s Memory.”

Valentina Flores is an editorial fellow with PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program. A graduate of Bard College, in the fall they will begin a PhD in Jurisprudence and Social Policy at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Law, with plans to study the impact of incarceration on political membership and its spillover effects across families and communities.