New Alarms are Raised over Accreditation, Key to Academic Freedom and Free Expression and Students’ Future Prospects

Monthly Roundup, June

This post is part of a series from PEN America tracking the progress of educational gag orders and censorious legislative efforts against educational institutions nationwide. These bills are tracked in our Index, updated weekly.

The end of June marks the conclusion of most state legislative sessions. One new educational gag order and one higher education autonomy restriction became law in June, with others in Ohio and Texas going down narrowly to defeat. After reviewing these new laws, we examine an aspect of higher education governance that has increasingly been targeted in legislative censorship efforts and seems likely to figure centrally in next year’s legislative sessions: college and university accreditation. Undermining this pillar of our higher education system could not only pave the way for more higher education censorship; it could seriously damage educational quality at universities and could even threaten some students’ access to federal financial aid.

- Since January 2021, 309 educational gag order bills have been introduced in 45 different states

- 29 have become law in 17 states (4 are not currently in effect)

- Three additional states have enacted educational gag orders via policies or executive orders

- 130 million Americans live in the 19 states where an educational gag order is in effect

In higher ed alone:

- Since January 2021, 99 higher education gag orders have been introduced in 33 different states

- During the same period, 22 higher education autonomy restrictions have been introduced

- 13 higher ed provisions have become law or policy in 9 states, with a population of 73 million Americans

New Laws and State Policies

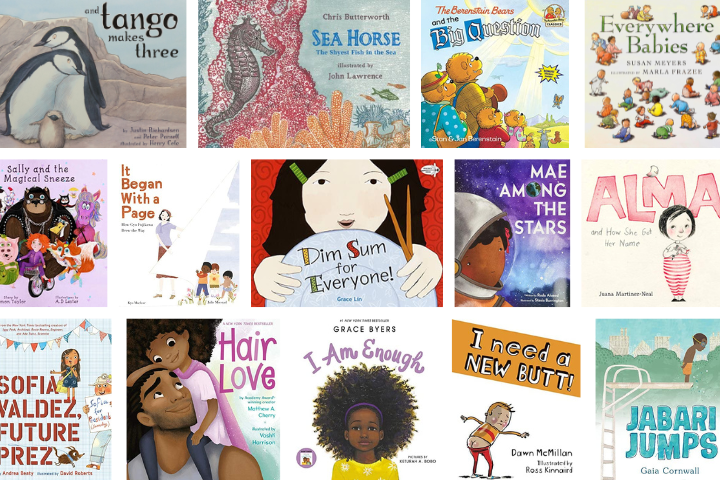

- Iowa’s SF 496, a “Don’t Say Gay” law, prohibits public K-12 schools from providing “any program, curriculum, test, survey, questionnaire, promotion, or instruction relating to gender identity or sexual orientation” to students in grades K-6.

- South Carolina’s HB 4300 prohibits public school districts from using any state funds in order to “provide instruction in, to teach, instruct, or train any administrator, teacher, staff member, or employee to adopt or believe, or to approve for use, make use of, or carry out standards, curricula, lesson plans, textbooks, instructional materials, or instructional practices that serve to inculcate” certain ideas related to race or sex. This prohibition applies for the duration of the 2023-24 fiscal year. Similar budget provisions were passed in the previous two fiscal years.

The War on Accreditation

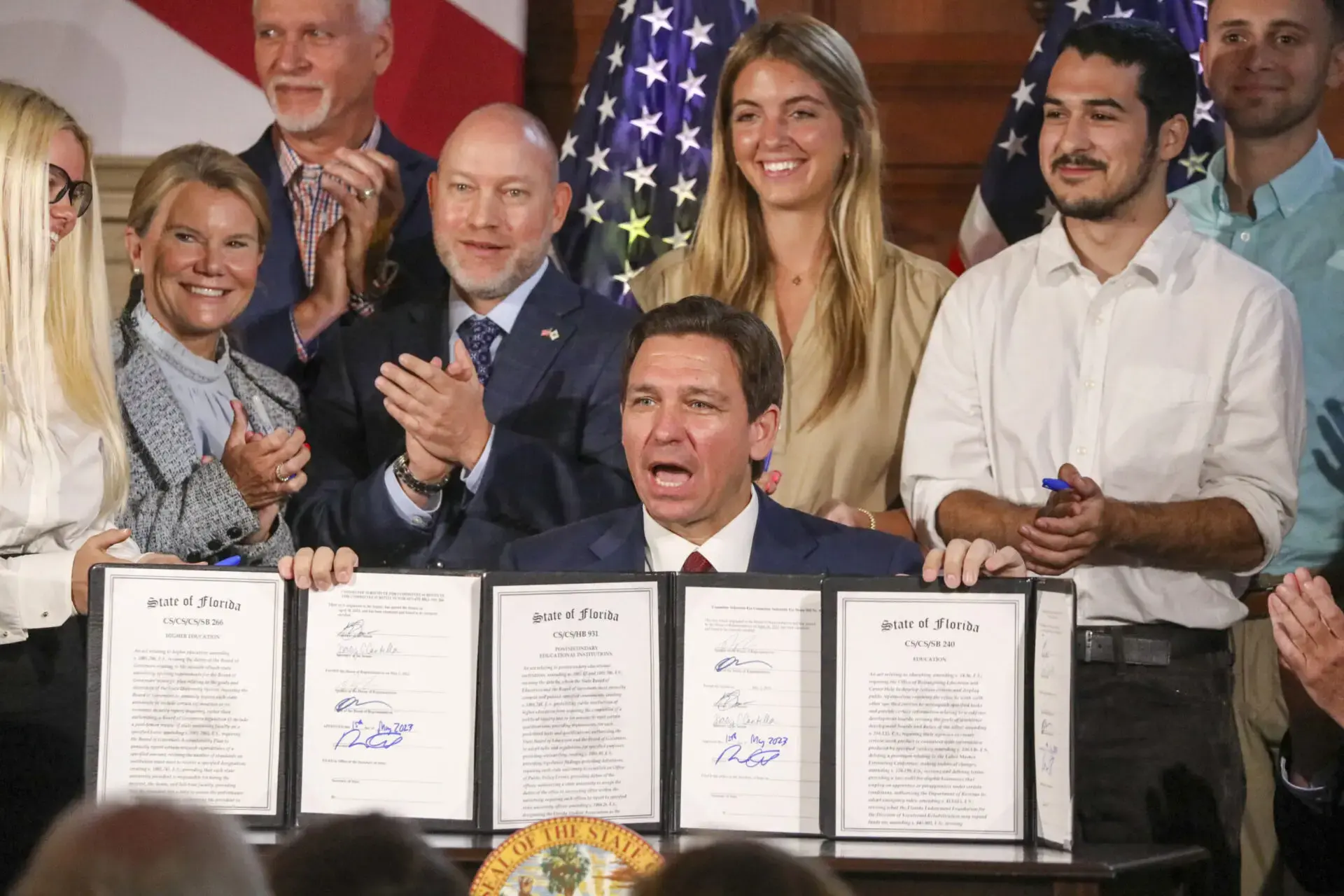

Former president Donald Trump has vowed to “fire” them. Republicans in Congress would like to restrict them. Florida governor Ron DeSantis wants the courts to break them. And Christopher Rufo, the chief architect of today’s “Critical Race Theory” panic, recently declared them his “next target.”

The culture wars have come for university accreditors.

For many Americans, the process by which colleges and universities are accredited may seem obscure or unimportant, but accreditation agencies matter. There are seven major bodies in the United States, the so-called “regional” accreditors, that accredit higher education institutions. Many majors and disciplines, such as nursing and engineering, also have their own accrediting bodies.

Simply put, accreditation is one of the principal guarantors of quality in America’s higher education system and one of the major ways students can differentiate between a reputable institution and a diploma mill. Each accreditor has its own standards for issues like graduation rates, financial health, and curricula. Accredited institutions themselves help develop these standards as well as plans for their implementation and evaluation. Ultimately, public and private universities must meet these standards to acquire and maintain accreditation.

And they have a very good reason to do so. Under the Federal Higher Education Act, unless a college is accredited by a federally recognized agency, its students are ineligible for Pell grants, federal loans, and work-study funds; nearly 84% of all college students rely on this financial support. Without accreditation, they may also have difficulty getting their degrees recognized by prospective employers or licensing boards. For the majority of universities, de-accreditation amounts to a death sentence.

This is the dynamic that some lawmakers and commentators want to change, and for one very specific reason: because accrediting bodies are a shield against government censorship.

Accreditation and Political Interference

In addition to ensuring academic quality and financial stability at colleges and universities, accreditation agencies represent one of the last lines of defense against undue political interference in university governance. As one of the regional accreditors, the Higher Learning Commission, explains in its accreditation standards, a college or university governing board must preserve “its independence from undue influence on the part of donors, elected officials, ownership interests or other external parties.”

Of course, there is and ought to be some role for lawmakers in how public universities are run; after all, these are public institutions. Still, for the academic mission to succeed, and for intellectual freedom to be sustained, that role must be carefully circumscribed. To see why, one need only look to Florida’s New College, where a cadre of political operatives is wreaking havoc on the institution at the behest of Gov. Ron DeSantis, who appointed them to the Board of Trustees. Or consider North Idaho College, where months of political rancor, lawsuits, and counter-lawsuits within the college’s senior leadership have escalated to the point where accreditation is at risk.

Situations as extreme as this are rare. More typical are cases where university leaders, often under the influence of state authorities, lawmakers, or political appointees, infringe on commitments to academic freedom or transparency. In these cases, accreditors simply rebuke the offending institution or remind it of its obligations under the terms of its accreditation. So for example, after the University of Florida blocked three political science professors from testifying against the state in 2021, the university’s accreditor – the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACS) – launched an investigation. Similarly, last April, when the University of North Carolina Board of Trustees appeared to be developing a new academic curriculum without faculty input, SACS notified the board that it was under scrutiny.

In neither case was the university’s accreditation ever threatened. Nevertheless, these notifications from accreditors carried great weight. After SACS announced its intention to investigate the University of Florida, the leadership there quickly reversed itself and allowed the professors to testify. Following its own run-in with SACS, the University of North Carolina’s Board of Trustees backed down as well. For politicians trying to use university governance processes to bring universities under their control, these actions by accreditors were a key obstacle.

Accreditation and Legislative Censorship

Since 2021, and especially in 2023, the threat of losing accreditation has served as a key deterrent to virtually all types of state legislative censorship efforts directed at higher education.

Educational Gag Orders

Over the past three years, higher education advocates have repeatedly cited accreditation standards in their defense against educational gag orders. Virtually every accrediting agency in the country has some sort of standard related to academic freedom. For example, the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, which accredits most institutions in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, requires that members demonstrate “a commitment to academic freedom, freedom of expression, and respect for intellectual property rights.” To qualify for accreditation from the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (covering the Rocky Mountain states and the Pacific Northwest), a university must show that it “adheres to the principles of academic freedom” and “actively promotes an environment that supports independent thought in the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge.”

Educational gag orders are about as clear a violation of these standards as one is likely to find. This point was driven home in two statements signed by the accreditation agencies themselves. A June 2021 joint statement co-organized by PEN America, the American Association of Colleges and Universities, the American Association of University Professors, and the American Historical Association – and signed by over 150 organizations, including all seven of the regional accreditors – noted that “these legislative efforts seek to substitute political mandates for the considered judgment of professional educators, hindering students’ ability to learn and engage in critical thinking across differences and disagreements.” A March 2022 community statement organized by the American Council on Education and signed by more than 100 academic associations, including six of the seven regional accreditors, also denounced lawmakers’ efforts to “suppress inquiry, curb discussion, and limit what can be studied.” The statement went on to warn that educational gag orders “[threaten] our civic health and the ability of the United States to compete globally.”

As PEN America and AAC&U explained in a follow-up statement, “Colleges and universities forced to comply with political edicts governing curricula and classroom discussions may forfeit their eligibility for accreditation, a drastic result that could compromise students’ eligibility for federal financial aid and place the institutions themselves in jeopardy.” Officials from the Higher Learning Commission, which covers most institutions in the Midwest, agreed. In March 2022, they warned Ohio lawmakers that passage of an educational gag order then under consideration would likely cost the state’s universities their accreditation. Similar warnings have been issued by university leaders, faculty, and students in Mississippi, Missouri, and virtually every other state where an educational gag order has been proposed.

Tenure Restrictions

Higher education advocates have also marshaled the power of accreditation agencies to defend faculty tenure. The initial draft of Texas’s SB 18 this year would have ended tenure for all public colleges and universities in the state, but Texas A&M University System vice chancellor James Hallmark testified that there were “concerns in terms of accreditation, reputation [and] rankings…the kinds of things that matter…[for] a national player in the higher education market.” Faculty at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill also expressed concern that HB 715, another anti-tenure bill, would threaten the university’s accreditation. These defenses worked, and tenure in both states survived these legislative threats.

The most successful use of accreditation to defeat legislative restrictions on tenure this year occurred in North Dakota, where HB 1446 would have, as part of a pilot program, severely limited tenure protections at two state universities. After the bill passed the state house, Larry Isaak, a former chancellor of the North Dakota University System, warned the Senate Education Committee of the bill’s potential impact on accreditation:

Political interference in employment of faculty and administrators at what is now [North Dakota State University] in the 1930s resulted in loss of institutional accreditation. Institution and program accrediting agencies may find HB 1446 to be unwarranted, unconstitutional interference in effective administration of NDUS institutions under the governance structure established and administered by the [State Board of Higher Education]. It happened before. The loss of accreditation of an institution or program will have devastating consequences to students and people of the state if an institution or program accreditation is lost.

Isaak’s testimony and subsequent comments to the media raised sufficient concerns that journalists confronted the bill’s sponsor, House Majority Leader Mike Lefor, with questions about accreditation issues; he replied by suggesting falsely that accreditors in other states had “vetted this already.” Ultimately, enough Republican lawmakers were concerned about the issues Isaak raised that the bill was defeated in the state senate by a single vote.

DEI Bans

Finally, accreditation has also served as a bulwark for defending diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives against legislative bans. Currently, six of the seven major regional accrediting bodies have some sort of standard related to DEI, though – contrary to some criticisms on the right – these standards are not especially onerous. For example, the Higher Learning Commission’s requirements on DEI consist entirely of the following:

- The institution’s processes and activities demonstrate inclusive and equitable treatment of diverse populations. The institution fosters a climate of respect among all students, faculty, staff, and administrators from a range of diverse backgrounds, ideas, and perspectives. [Sec. 1C]

- The education offered by the institution recognizes the human and cultural diversity, and provides students with growth opportunities and lifelong skills to live and work in a multicultural world. [Sec. 3B]

- The institution strives to ensure that the overall composition of its faculty and staff reflects human diversity as appropriate within its mission and for the constituencies it serves. [Sec. 3C]

These requirements are not a difficult bar to clear. Nevertheless, for lawmakers eager to eradicate all traces of “DEI,” these standards present an intolerable affront. In Texas, legislators responded by carving out an exception to their DEI ban “for the purposes of applying for a grant or complying with the terms of accreditation by an accrediting agency.” Florida did likewise, banning all DEI initiatives except those necessary “for obtaining or retaining institutional or discipline-specific accreditation.” A revision of Ohio SB 83, which ultimately failed to pass, carved out the same exception. These exceptions are important victories, but were grudgingly given and represent for some lawmakers an unacceptable compromise.

The Coming Wave of Attacks

In short, accreditors are one of higher education’s final lines of defense against state-backed censorship. But it is unclear for how much longer this will be the case.

Last month, congressional Republicans introduced the Fairness in Higher Education Accreditation Act. This bill would amend the Higher Education Act of 1965 to prohibit accreditors from requiring that universities “support or commit to supporting the disparate treatment of any individual or group of individuals on the basis of sex, race, or ethnicity.” This restriction, Its sponsors claimed, will help to “combat wokeness on campus.” A few weeks later, Florida sued the federal government in an attempt to sever the link between accreditation and federal aid altogether.

Even if the suit fails, Florida has already prepared a backup plan: a new law that allows state universities to sue an accreditor for any financial harm it suffers due to a “retaliatory or adverse action” taken by an accreditor. In other words, Florida can sue an accreditor that enforces its own standards. This preposterous idea strikes at the very purpose of accreditation. Nonetheless, it’s already been copycatted: Texas’s new DEI ban contains similar language.

This legislation enters a landscape where nonpartisan accreditors are being increasingly politicized by some conservative activists. Last month, a Heritage Foundation report called for Congress to “dismantle the higher education accreditation cartel” by creating “an alternate path to Title IV funding eligibility” – that is, by decoupling accreditors’ seal of approval from eligibility for federal student financial aid. The American Council of Trustees and Alumni, which has sought to undermine accreditation for decades, wrote in June that “the recent spate of legislation introduced at the state level seeking to challenge the national (formerly regional) accreditors is unprecedented.” They are right.

Academic freedom and free speech on campus have many layers of defense: the U.S. Constitution, state law, faculty contracts, and outside advocacy groups, to name only a few. Accreditation agencies are rarely counted among these defenses; yet they are an indispensable ally to those who value open inquiry on campus. This means that they are also being targeted as an enemy to those who oppose it. In the 2024 state legislative sessions, accreditation seems likely to be a central target of higher education censors. Free expression advocates should make its defense a central priority.

This update from PEN America was compiled by Jeffrey Sachs and Jeremy C. Young.