Book bans and educational gag orders erode key tenets of academic freedom, violate free expression, and mirror global trends among writers at risk, PEN America and PEN International detail in a joint submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to education.

PEN America and PEN International are pleased to jointly submit a contribution to the Special Rapporteur’s report on academic freedom and free expression in educational institutions.

PEN America and PEN International are part of a global PEN network which champions the freedom to write, celebrates the power of words to transform the world, and defends free expression. PEN International is the international secretariat for the PEN network of 130 centers in 90 countries.

As defenders and supporters of writers, readers, and free expression in education, the PEN network has a distinct responsibility to ensure that academic freedom and free expression protect students, educators, and other academic staff members’ rights to freely access books, teach complex topics, and encourage the exploration of individual inquiry.

This submission will focus largely on threats to academic freedom in the United States, but it also includes a small section on international scholar-writers and trends in threats against their academic freedom.

Academic Freedom in the United States

Academic freedom has been described by the United States Supreme Court as “a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.”1Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967). As a practical matter, however, the definition and enforcement of academic freedom is not enshrined in legislation or jurisprudence in the United States; rather, it exists primarily as a matter of robust institutional precedent in higher education.2As historian Henry Reichman explains, academic freedom is grounded less in First Amendment jurisprudence than in “common law tradition and contractual protections.” Henry Reichman, Understanding Academic Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021), 153.

The most commonly held definition of academic freedom derives from the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), a national higher education advocacy group. According to the AAUP, academic freedom is the “freedom of a teacher or researcher in higher education to investigate and discuss the issues in his or her academic field, and to teach or publish findings without interference from political figures, boards of trustees, donors, or other entities. Academic freedom also protects the right of a faculty member to speak freely when participating in institutional governance, as well as to speak freely as a citizen.” The protections of academic freedom are anchored in the belief that higher education exists to further the “common good,” which “depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition.” Academic freedom secures the conditions under which university personnel are able to research and teach with fealty to the standards of their disciplines, unhindered by politically or ideologically motivated interference.

The AAUP insists that university students, like professors, deserve robust protections for speech, expression, and association. PEN America has repeatedly affirmed the rights of university students to express and be exposed to a diversity of viewpoints. For example, the PEN America Principles of Campus Free Speech states that campus groups should be free to invite speakers of diverse ideological perspectives, even those many find offensive.

While academic freedom is an institutional precedent in higher education, it is not customarily applied at the primary and secondary school level in the same manner. However, landmark legal decisions in the U.S. have defended students and teachers’ rights to freedom of speech in public schools under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.3Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. The U.S. Supreme Court has, for example, decided in favor of certain protections for students’ non-disruptive speech at school4Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969). and against “narrowly partisan and political” discretion of content in school libraries.5Bd. of Educ., Island Trees Union Free Sch. Dist. No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982). These protections amount to an acknowledgement of the importance of academic freedom in schools.

In addition, the United States has “long-standing norms around institutional autonomy [that] insulate public higher education institutions from undue political interference, enabling them to craft their own mission statements and make their own programmatic decisions, and preserving them as spaces where ideas both popular and unpopular can be discussed, studied, and learned from.”6See also “Statement by the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) and PEN America regarding Recent Legislative Restrictions on Teaching and Learning,” June 8, 2022, PEN America, https://pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Statement-by-AACU-and-PEN-2.pdf. Institutional autonomy from undue political or ideological interference by the government is a requirement of most university accreditation bodies, and has been described as a kind of “institutional academic freedom.”7Timothy Reese Cain, “Accreditation, Academic Freedom, and Institutional Autonomy: Historical Precedents and Modern Imperatives,” Journal of Academic Freedom (2023) 14.

PEN America and PEN International believe that academic freedom can only flourish in environments where educators and students enjoy robust protections for speech and association and educational institutions are protected from government interference on ideological grounds.

Challenges to Academic Freedom in the United States

Main Challenges

PEN America has researched and analyzed two primary tactics that have had widespread negative impact on academic freedom and free expression across the education sector, namely educational gag orders and book bans.

Educational Gag Orders

PEN America defines educational gag orders as legislative restrictions on the freedom to learn and teach. Forty-six of 50 US state legislatures have introduced 307 educational gag order bills or policies since January 2021. Forty of these bills have become law in twenty-two states.8See PEN America’s Index of Educational Gag Orders, https://airtable.com/appg59iDuPhlLPPFp/shrtwubfBUo2tuHyO/tbl49yod7l01o0TCk/viw6VOxb6SUYd5nXM While it is difficult to accurately estimate the total number of educators affected by these laws and policies, a conservative estimate would put the number at approximately 1.3 million public school teachers and 100,000 public college and university faculty.9Estimate of full-time public college and university faculty only. Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2022, Table 314.50, nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_314.50.asp Estimate of full-time public school teachers only. Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data, 2021–22, nces.ed.gov/ccd/elsi/. Does not include private K–12 school faculty affected by Indiana HB 1608. The students who have been directly affected—through canceled classes, censored teachers, and decimated school library collections—likely number in the millions. The chilling effect on public education across the country is certainly much larger.

Higher Education

Legislators in 33 states10Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming. introduced a total of 100 educational gag order bills in higher education settings between January 2021 and November 2023. As of January 2024, 9 educational gag orders are in effect in 8 states.11Florida, Idaho, Iowa, Mississippi, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee.

During the 2021 and 2022 state legislative sessions, the overwhelming majority of the bills targeting higher education sought to restrict faculty speech directly, particularly with regard to discussions of race and racism. North Dakota’s SB 2247 prohibits public college and university faculty from asking students about their “ideological or political viewpoints” and prohibits employee trainings on a list of “specified concepts,” many of which discuss race or sex.

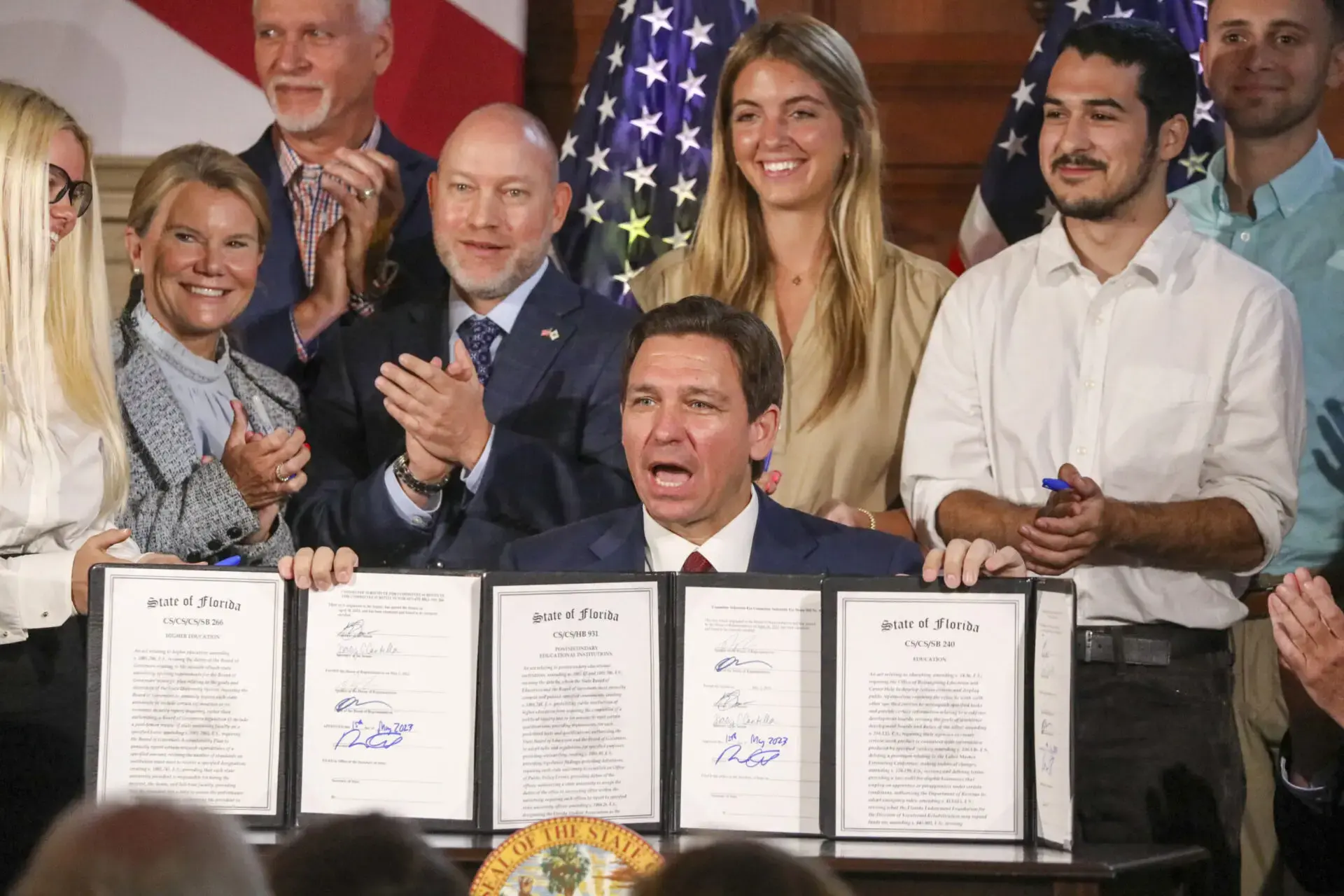

Rather than censoring speech directly, a number of additional bills were introduced in 2023, and three became law, that targeted institutional autonomy with the following restrictions:

- Curricular control: Legislation introduced to assert state control over curricula include Florida’s SB 266/HB 999, which prohibits expending state or federal funding for programs or campus activity that violates the Stop W.O.K.E. Act (HB 7). It requires that general education courses may not “distort significant historical events” or teach “identity politics”.

- Bans on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and initiatives: These bills undermine free expression on campus by asserting direct ideological control over how universities operate. Texas’s SB 17, for example, calls into question the legality of groups like UT-Austin’s Latinx Community Affairs. The bill prohibits institutions from “promoting policies or procedures designed or implemented in reference to race, color, or ethnicity.”

- Tenure restrictions: Legislation introduced to undermine tenure12For more on tenure, see AAUP’s 1940 “Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure,” https://www.aaup.org/report/1940-statement-principles-academic-freedom-and-tenure includes Iowa’s HF 48; North Carolina’s HB 715; and Mississippi’s SB 2785. While none of these bills became law, the idea of weakening robust tenure practices has been incorporated in new laws such as Florida’s SB 266.

- Accreditation restrictions: While accreditation agencies have sometimes themselves undermined academic freedom, accreditation acts as a bulwark against undue political influence on university governing boards.13For more on the relationship between accreditation and academic freedom, see Timothy Reese Cain, “Accreditation, Academic Freedom, and Institutional Autonomy: Historical Precedents and Modern Imperatives,” AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom 14 (2023), https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/Cain_JAF14.pdf. North Carolina’s HB 8 requires public colleges and universities to switch accreditors each review cycle, a time-consuming and costly provision copied from Florida’s SB 7044.

Primary and Secondary Education

Laws have also restricted teaching and learning in primary and secondary schools in ways that undermine free expression and academic freedom, including through:

- Direct censorship of teaching materials: Mississippi was the first state to introduce an educational gag order, namely SB 2538, which prohibited using state funds to teach the New York Times’ 1619 Project.14The 1619 Project is a multimedia initiative by The New York Times Magazine that seeks to reexamine and broaden the historical narrative of the United States by highlighting the profound impact of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans throughout American history, with a focus on the year 1619 when the first enslaved Africans arrived in the English colonies. It includes essays, interactive elements, and educational resources to promote a deeper understanding of how slavery has shaped the nation’s past and present. See https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html It did not ultimately pass into law but inspired over 23 bills targeting the 1619 Project; Texas’s SB3 has become law.

- Preventing discussion of LGBTQ+ identities: In 2023, more than a third of all K–12 educational gag orders introduced in state legislatures sought to restrict how educators discuss sexual orientation and gender identity. Most of these bills are modeled after Florida’s HB 1557, known colloquially to critics as the “Don’t Say Gay” Act.

- Threats to social-emotional learning: A small but concerning subset of recently introduced bills have targeted this pedagogical approach to learning, misidentifying the field as a Trojan horse for “critical race theory” and “liberal indoctrination”. Oklahoma’s unsuccessful SB 1027, for instance, prevents schools from promoting civic engagement, among other restrictions on social-emotional skills.

The impact of these bills and laws has a clear chilling effect on free expression in the classroom. If educators who raise issues related to race, gender, or history face serious legal, financial, or reputational consequences—if discussions of, say, the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements become too risky—fear will squelch free expression. Even when political leaders merely threaten to introduce educational gag orders, or when they are introduced but do not become law, they still send a potent message that educators are being watched and that ideological redlines exist. Students’ academic freedom is restricted indirectly when educators are unable to teach or hold discussions without fear of reprisal.

School Book Bans

PEN America defines book bans as instances where students’ access to books in school libraries and classrooms in the United States is restricted or diminished for either limited or indefinite periods of time.

Educators and students in primary and secondary schools in the US face significant challenges to their free expression and academic freedom through book bans. Between July 2021 and June 2023, PEN America recorded 5,894 instances of school book bans across 41 states. The swath of book bans includes 3,362 instances of books banned in public schools in the 22-23 school year. This is an increase of 33% from the 21-22 school year. While PEN America specifically records instances of book bans in public primary and secondary schools, we note that the current trend also affects public libraries.

Groups and individuals pushing to ban books have overwhelmingly targeted books with stories by and about people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals. There has also been a concerted effort to suppress content related to sex and sexuality, including fiction and non-fiction books that touch on puberty, dating, sexual consent, teen pregnancy, and abuse. Censorship of this content deprives students of vital information about their bodies and relationships that can help them grow into healthy adults. Where the interpretation of the law is unclear, librarians and teachers have opted to cautiously curate shelves and preemptively censor lessons for fear of violating a law.

Book bans have an especially pernicious impact on individuals from historically marginalized communities and identities. Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer has been one of the most banned books across the U.S. since 2021. Many laws have effectively restricted access to books and teaching materials related to LGBTQ+ topics on the ostensible basis of “obscenity”. The rhetoric marshaled to justify banning books containing LGBTQ+ characters or themes evokes long-standing stereotypes that stigmatize LGBTQ+ people as inherently sexual or pornographic.

Outside of an educational setting, authors and publishers are impacted by book bans, in turn, making books more difficult to publish and distribute to an important audience.

Gaps in the Legal Framework

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that States generally have the authority to make decisions in public educational institutions. Since academic freedom is not codified in U.S. law, educators, students, and other academic staff must rely on the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution or state constitutional provisions to legally protect them against violations of, and other threats to, academic freedom. However, the Supreme Court has not explicitly held that the First Amendment requires academic freedom, meaning that these claims must draw on a patchwork of case law and dicta to succeed in defending free expression rights.

Gaps in the legal framework are particularly prevalent in primary and secondary schools because minors are not entitled to the same rights as adults, and academic freedom is not customarily recognized outside of U.S. higher education institutions. The 1982 ruling Bd. of Educ., Island Trees Union Free Sch. Dist. No. 26 v. Pico is the only U.S. Supreme Court case on book bans. The court ruled that the book bans were unconstitutional in this case, but the fractured plurality opinion arguing that students have a right to receive information in public schools does not have precedential authority.15Bd. of Educ., Island Trees Union Free Sch. Dist. No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982). Legislation to ban books has also misleadingly drawn language from the definition of obscenity articulated in Miller v. California.16Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). Lawmakers have created their own definitions of “obscenity” that go far beyond the constitutional standard. A number of politicians have exploited the fact that “obscenity” is not clearly defined in the law and have compelled the removal of books from school shelves by stigmatizing them as “obscene”.

Across the sector, public educational institutions have argued that book bans and educational gag orders are “government speech”,17The “government speech doctrine” holds that the government is not barred by the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment from determining the content of what it says and can engage in viewpoint discrimination. See “Amdt1.7.8.2 Government Speech and Government as Speaker”, constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt1-7-8-2/ALDE_00013545/#ALDF_00025675 meaning schools could be shielded from claims they are violating the First Amendment when they restrict students’ access to books or censor classroom discussions. The Escambia County School District has argued that banning books in schools is a form of government speech. This argument has also been used with regard to higher education gag orders, such as in the Florida lawsuit Pernell v. Lamb challenging HB 7.

Parallel Trends Internationally

PEN International and PEN America document threats to writers in their PEN International Case List, Writers at Risk Database and the Freedom to Write Index. The Writers at Risk Database includes 177 cases of at-risk writer-scholars in several countries; most are from China (48), Iran (21), Türkyie (18) and India (17) and Saudi Arabia (11). Writer-scholars tracked in the Database are typically under threat for challenging social norms through their platform as academics and/or their writing, and expressing their opinions and expertise on current affairs. Topics that typically put writer-scholars at risk are similar to those in the United States:

- History: People writing about history with a critical lens have been threatened with or imprisoned by the government. Russian historian Yury Dmitriev researched Stalinist atrocities and uncovered mass graves in Karelia, and he is currently serving a 15-year sentence for baseless charges on sexual assault.

- Ethnic and cultural minorities: People who study and write about minority ethnic and cultural heritages are persecuted and even prosecuted. Turkish-Kurdish scholar of literature Yavuz Ekinci has been convicted for his social media posts. He lives in exile in Germany, but his work continues to be threatened; his book was banned in Türkyie ostensibly for sympathizing with the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party).

- Policy criticism: People who use their academic expertise actively speak against government policies are also threatened and harassed, or even jailed. Professor Xu Zhangrun was barred from teaching at Tsinghua University in 2019 after he criticized Chinese President Xi Jinping’s mandate; he was later placed under house arrest for writing an essay about the Chinese government’s COVID-19 policies.

Freedom of Expression in Teaching and Access to Books

In higher education, professors have not traditionally been mandated to remain “neutral,” as academic freedom affords them the ability to express their opinions. However, at the primary and secondary education level, free expression is narrow, as challenges outlined above increasingly limit educators’ expression. In some states, teachers have cut lessons about prominent historical and cultural figures from their plans because they fear breaking the law. One Tennessee arts educator says she stopped teaching the art of Keith Haring and Frida Kahlo because of SB 623—which requires parental notice to teach concepts related to race and sex—because the artists’ sexual orientation and gender identity are too important in contextualizing their work.

Within public primary and secondary schools in the United States, educational materials are curated by teachers and librarians in accordance with state and district-level laws and guidelines. As a resource, standards and best practices are developed and outlined by professional organizations, such as the National Council of Teachers of English or American Library Association. Some materials, like the majority of school library books, are optional, while others, like assigned classroom textbooks, are mandatory.

Increasingly, states are severely limiting the ability of teachers and librarians to have trust and autonomy in being able to curate educational materials appropriately, leading to book removals. One example is Iowa’s 2023 law SF 496, which requires schools to adopt an “age appropriate, multicultural and gender-fair approach.” As a result, school librarians who stock any book with a “sex act” risk disciplinary action. In Iowa’s Urbandale public school district George Orwell’s 1984 and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye were among 400 titles removed to comply with SF 496. Under a 2022 law in Missouri, SB 775, school employees caught furnishing sexually explicit material to minors could face up to a year in jail. According to one school librarian operating under SB 775, “You second-guess everything that you’re purchasing so you wind up self-censoring, even though that’s not our goal. But you’re fearful.” Hundreds of books have been removed as a result of Missouri’s SB 775, and the law is being challenged in the Circuit Court in Kansas City. This comes as a result of both highly-coordinated, well-resourced political advocacy groups and censorious legislation that targets teachers, librarians, and the content they are allowed to curate for students.

Recommendations

To the U.S. Federal Government:

- The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights should investigate, and challenge the implementation of educational gag orders and other laws that restrict academic freedom and free expression on campus.

- The U.S. Department of Education should continue efforts to process and investigate complaints submitted to the Office of Civil Rights on cases arising from book bans and educational censorship that could constitute discrimination;

- The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights should offer guidance and clarification to districts affirming primary and secondary students’ and teachers’ robust rights to academic freedom;

- The U.S. Department of Education should continue to support those affected by book bans and educational censorship.

To the U.S. Congress:

- Pass the Fight Book Bans Act, the Books Save Lives Act, and the Right to Read Act at the federal level to protect the freedoms to read and access information within K-12 schools;

- Hold additional roundtable and congressional hearings to raise awareness of threats to free expression, censorship, and book bans within K-12 schools.

- Suspend investigations into private universities that concern matters not relevant to federal law, such as plagiarism accusations against individual faculty members.

To the Higher Education Sector:

- Unite to advocate against educational gag orders in whole-sector coalitions across institutions.

To UN bodies, UN Member States:

- Issue statements of condemnation against US states that pass educational gag orders.

- Issue statements supporting the freedom to read in the US and condemning restrictions on the freedom to read (such as book bans).

To Civil Society:

- Oppose educational gag orders as a central threat to democracy.

- Utilize resources to oppose book bans, curriculum censorship, and other types of K-12 educational censorship.