In the final weeks of an election season that has featured false claims of immigrants eating dogs and cats, deepfake videos of presidential candidates, and sophisticated foreign influence campaigns, there are plenty of worries to keep disinformation experts up at night.

While much attention has gone to the rise of artificial intelligence in easily creating sophisticated disinformation, five top experts gathered by PEN America felt it was too soon to declare victory or defeat about its danger to the electoral process. But generative AI is far from the only threat to the information ecosystem.

“It’s like every fact-check is a drop in the ocean when you’re fighting against this much of a deluge of disinformation,” said Nina Jankowicz, an expert on disinformation and co-founder of the American Sunlight Project.

To discuss the serious dangers of disinformation ahead of Election Day, PEN America brought together top journalists and experts for an Oct. 2 panel discussion, “Election Countdown: Combating the Most Dangerous Disinformation Trends.” These are the trends that worry the experts most:

1. Hyperpartisan Bubbles

It’s increasingly difficult to get past “filter bubbles” to deliver facts, said Brett Neely, supervising editor of NPR’s disinformation reporting team.

“It’s like pollution, and we’re on a heavy smog alert cycle,” Neely said. “The fact that even something as preposterous as the claims around immigrants in Ohio eating pets took sustained debunking, and even then, you never saw anyone withdrawing their claims. It just kind of moved on. It is, I think, a sense that the filter bubbles are getting stronger and stronger, and the ability to reach people with accurate information that’s been vetted – it feels very frustrating. It feels very fraught. Whether that’s significantly worse or different between now and 2020, it’s a little hard to say, but it does really feel like we’re in an informational crisis.”

2. Foreign Interference

One of the dangers that Tiffany Hsu, disinformation reporter for The New York Times, is watching most closely is the increasing sophistication of foreign disinformation efforts, particularly by Russia, China, and Iran.

“In addition to using the brute-force methods that they’ve used in the past, like sockpuppet campaigns, that sort of thing, they seem to be getting smarter about what they’re doing. They’re using more AI. They’re using more localized techniques. You had the whole Tenant Media kerfuffle involving right-wing American commentators that were on their payroll from Russia. You’ve got China that’s increasingly tapping technological advances to push their propaganda. You’ve got Iran, which is hacking into presidential campaigns, or attempting to.”

Hsu added, “what happens is, you might be talking to your neighbor and they may say something that is clearly a false narrative, but what the average American might not realize is that they’re getting that from a foreign source.”

3. The Decline of Content Moderation

Panelists described a growing disinterest in content moderation by social media platforms – leading to both a rise in the spread of disinformation and a decline in transparency.

“The thing that keeps me up at night is that we’ll continue to see a race to the bottom by social media platforms in terms of responding to this issue,” said Samuel Woolley, University of Pittsburgh professor, disinformation researcher and author. “We were seeing a lot of action in the space, then suddenly, we’ve been seeing a lot of inaction and actually willful negligence, led by some folks that I’m sure I don’t need to mention.”

Hsu chalked it up to a mix of fatigue – “because they’re getting criticized from both sides of the political spectrum for what they’ve managed to do and not do on the content moderation front” – but also growing aggression from the platforms and their allies against people who want transparency. The latter has resulted in withdrawing access to independent researchers, and partisan Congressional attacks on research centers. “It’s very concerning, because without transparency, without comprehension of what’s driving changes in the quality of discourse, we can’t adapt these platforms for the better.”

4. Political “Influencers”

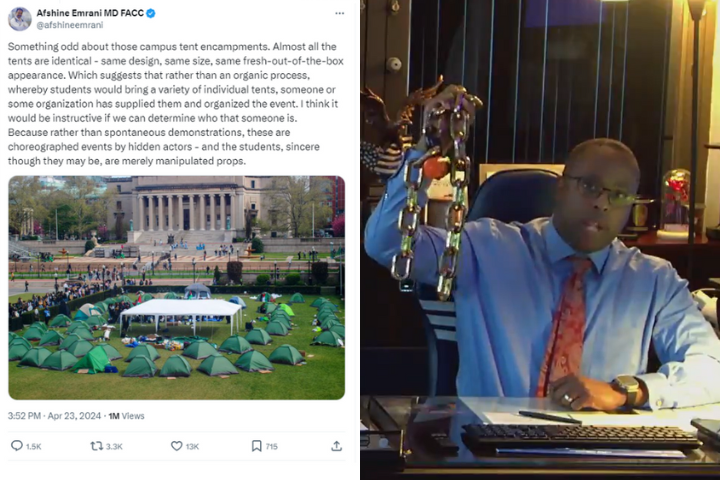

In the past, those who spread disinformation turned to bots or coordinated groups of people to push messages on social media. A new innovation that is racing ahead during this election is the use of influencers by super PACs and shadowy money organizations, Woolley said.

“What that looks like is that these groups will hire well-placed individuals – sometimes, yes, they’re celebrity influencers, but more often than not, they’re what we call nano- or micro-influencers. They’re people with smaller-scale followings that are focused on speaking to a specific community, for instance, Cuban Americans in Miami or- blue-collar workers in Pittsburgh.”

Because these people are “the bread and butter” for platforms, there’s little incentive to hold them accountable. If an influencer is selling a product, the platforms must disclose that it is a paid ad – but the same is not true for political messages.

5. Encrypted Messaging

There’s an oversaturation of misleading and hyper-partisan content in spaces like the messaging app WhatsApp, said Roberta Braga, founder of the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas, which tracks disinformation in Latin America and with Latino Americans. “But I think that the difference is that more and more, that content is not outright false or even easy to identify as false, it’s just massively decontextualized or takes one little grain of truth and manipulates it so aggressively that people take that story about the state of the world and build into it.”

Woolley will have a book published next year called Encrypted Propaganda, which will describe how messaging apps are being used for the same kinds of influence campaigns happening on social media to manipulate public opinion. “So looking to places like India and Brazil, you can see that really in action right now.”

6. Decline of Trust

Propaganda isn’t always about persuasion – it’s about making people question whether anything is true, which in turn encourages people to lose faith in institutions and not participate as much in politics, Neely said.

Braga’s organization has seen deep penetration of conspiracy narratives about elites conspiring with social media companies and news outlets, or a deep state of political actors. Most people say they don’t believe everything they see online, amid growing familiarity with disinformation narratives. “But I think that also means that they’re also skeptical of credible information, and so that’s something that I think we should definitely keep an eye on in coming years,” she said.

In a poll earlier this year measuring Latino trust in election stakeholders, including journalists, fact-checkers, and political parties, Braga’s organization found the only stakeholders trusted across partisan lines were scientists and neighbors. Because of the heightened scrutiny, Hsu said she ends up “spending more time fact checking and bulletproofing my stories than I do reporting them.”

Even political candidates are cashing in on that skepticism – what Jankowicz called “the liar’s dividend.” “We’ve seen Donald Trump use that to cast doubt on Kamala Harris’s crowd sizes, and then, most recently, with the scandal with the North Carolina gubernatorial candidate who claimed that his distasteful posts on pornographic forums were actually AI-generated. We can just leave those facts there and let the audience decide what to do with them.”

7. Generative AI

Last, but not least – the panelists took a measured approach to evaluating the danger of AI. Some initial commentary about generative AI was alarmist, comparing the impact to nuclear weapons. More recent op-eds have declared that the fear of the impact of generative AI on elections was overblown. Woolley noted that there’s little data to inform that analysis.

One piece of AI-generated content might not change how a person votes, but Braga’s research has found that people who tend to believe disinformation often show high levels of interest in politics. “They’re conspiratorial in nature already, and they’re choosing to consume very hyper-partisan news and information.”

“Every major technological communications advancement helps unleash some level of political and societal instability, going back to the printing press, and sometimes it takes a long time to understand how that happens,” Neely added. “We’re in year three of something that is likely going to take us, as a society, 30 to 50 years to digest.”

Visit PEN America’s Facts Forward guide for more on how to fight disinformation.