As yet another year comes to a close, books and the people who write them have stood by as unwavering touchstones of comfort and solace, as reminders to why we do what we do. Over the course of the year, we had fruitful conversations with innumerable writers on their craft, struggles, hopes, and dreams. To end the year, we have rounded up some resonant words from ten authors featured in our PEN Ten interview series offering advice on picking up a pen as you go gently into the new year.

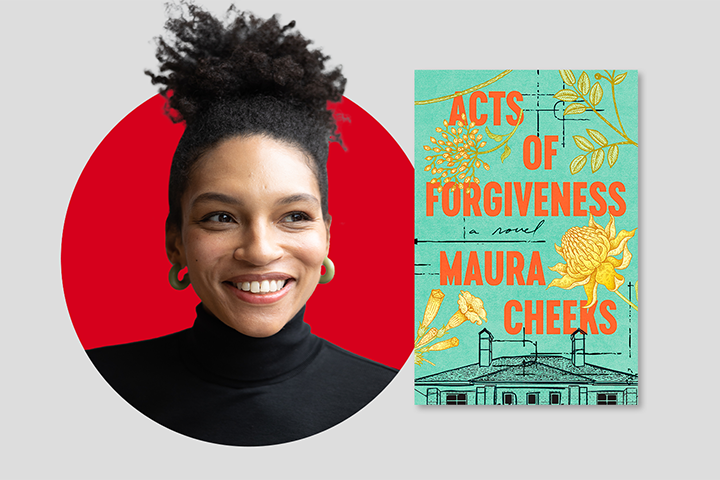

Maura Cheeks, author of Acts of Forgiveness, on advice for aspiring writers

I never wanted to hear this when I was starting out, but it is true that if you write, you are a writer. More specifically, if you work consistently on improving your craft, then you’re a writer. What that looks like will be different for you based on where you are in your life. It might mean waking up 30 minutes earlier so you can work on one sentence or one scene before your full-time job. It also might mean reading books on craft. One piece of advice I wish I had gotten earlier is to define what “being a writer” actually looks like for you. What does success mean? Be specific and set goals and then build on those goals once you start achieving them.

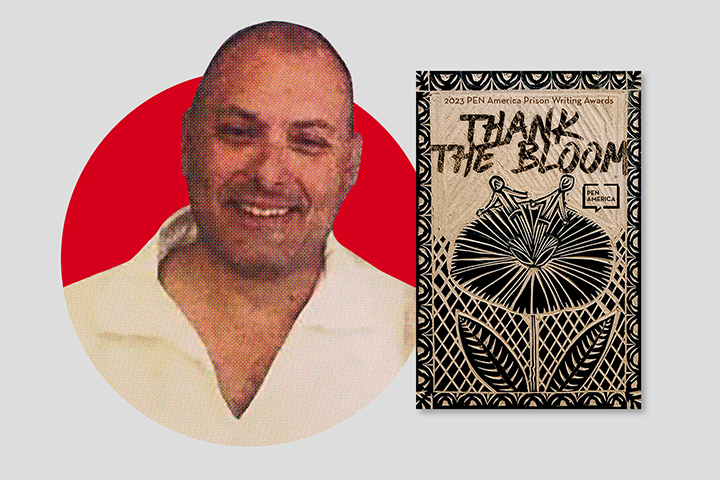

Matthew Mendoza, writer of short story “Hinges & Runners” (published in Thank the Bloom: 2023 Prison Writing Awards Anthology, PEN America 2024) on learning to write

One of my early mentors, Owen King, asked me if I thought that writing could be taught. The answer I gave was no. I don’t believe that it can be taught but it can be learned. Everything you need is in your favorite book. Description, dialogue, sentence structure—it’s all there. Including what should be left out.

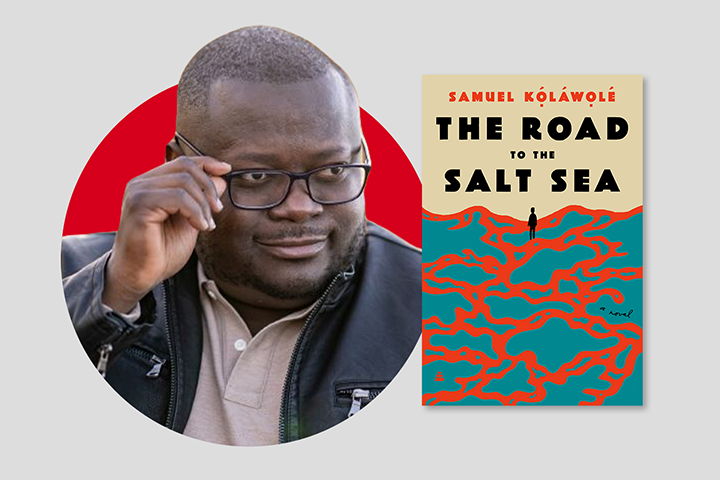

Samuel Kọ́láwọ́lé, author of The Road to the Salt Sea, on his creative process and getting into the zone

I have this weird habit of getting up early in the morning to write. The greatest time to write, in my opinion, is between three and seven in the morning when everything is quiet and your mind isn’t yet overtaken by the problems of the day. (Do what works for you.) I haven’t been writing much lately, but I still wake up around those hours. When I do, I sometimes do something else. Thinking and observing is also part of my process. Before they are turned into fiction, my ideas go through a protracted gestation stage. Making excursions to bookstores also inspires me. There’s something special about seeing or smelling the finished copy of a book.

Deborah Jackson Taffa, author of Whiskey Tender, on maintaining momentum

My creative process involves a great deal of patience. I write and rewrite single essays many times, and in between drafts I let them sit. In the last decade, I have let published pieces sit for years before returning to them. I have prioritized self-care over speed, and quality over publication as a motto. I never wanted to conflate writing with a desire to create a career. I helped run a construction company. I raised kids. I cooked thousands of meals for my family and washed an enormous amount of clothes. I scribbled and thought and remained obsessed with my project because I felt internal pressure to make sense of my story. I owed it to myself to take my time. Giving up was never a possibility.

Remica Bingham-Risher, author of Room Swept Home, on what she wished she knew before writing a book

I wish I knew how long this community could care for you. Poets are really some of the kindest, most patient, “care/full” as Lucille Clifton would’ve said it, and considerate human beings, that it would be okay to make my way among them again and again. I would’ve also liked to know then that there were plenty of Black poets writing—contemporary Black poets—who would bolster me. I’m so grateful to be among them now. I’m so fortunate to have a means to tell all these hidden and forgotten stories.

Sacha Lamb, author of The Forbidden Book, on advice to her younger self and queer writers

The biggest psychic obstacle I’ve had to overcome is the thought that my own queer experiences might not be legible enough to others. My advice is don’t self-censor and don’t self-reject. Others will question you enough, so don’t be your own first uncharitable critic.

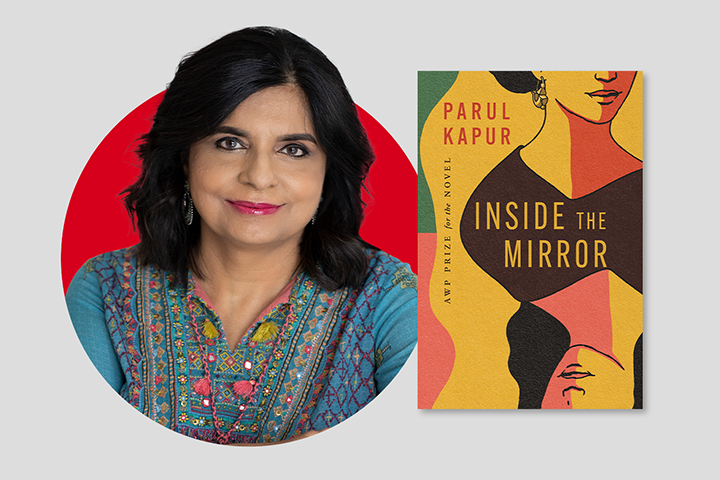

Parul Kapur, author of Inside The Mirror, on the surprising thing she learned while writing her book

I discovered I had the ability to give up. That can be a good thing, because it frees you. For twenty-five years, I worked doggedly on this novel. Finally, I revised the novel to my satisfaction, but I couldn’t find an agent because it was too long at 600 pages. It felt like a great disloyalty to put the manuscript away. I had been devoted to my characters for most of my adult life. And yet, as I sealed the pages up in a box, I felt it contained a great energy, a whole world, and I had a spurt of confidence that the book was alive and might one day make it into the world.

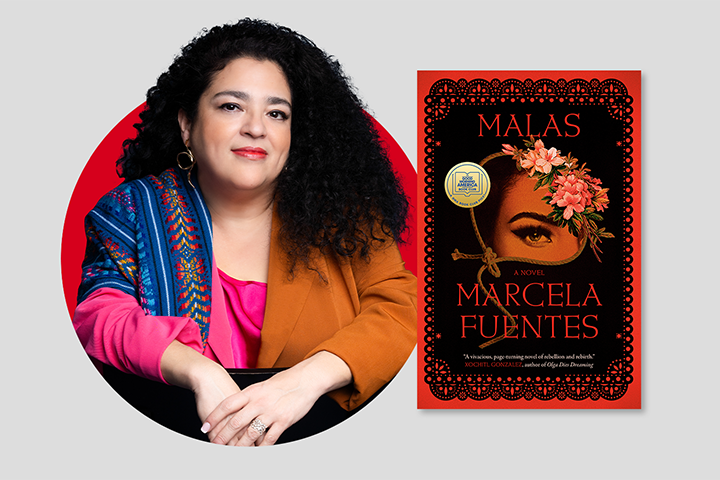

Marcela Fuentes, author of Malas, on advice to BIPOC writers trying to get published

Write the book you want to read, and write the very best book you can! Also, don’t be afraid to go big—send your work out, and keep sending it. Go to summer writing conferences, use your community networks and resources, share advice and information with writer friends. Trust your vision and trust your work.

Maame Blue, author of The Rest of You, on preserving memories for the younger generation

For me, writing this book was the perfect excuse to connect with the elders in my family; aunties, uncles, older cousins, and listen to their stories, to get a real sense of their experiences. My advice would be for younger generations to talk to those elders if they are able – ask questions, be curious and try to fill those gaps in their collective memory. If nothing else, it will likely bring you closer to an understanding of what came before you, and what pathways were laid out for you to arrive where you are today.

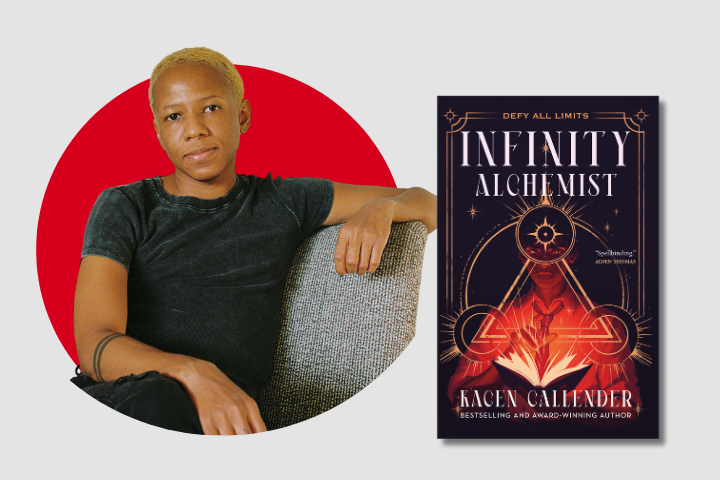

Kacen Callender, author of Infinity Alchemist, on writing your identity amidst increasing censorship

Work needs to be done to stop the censorship for young people today, but I also think about the books and stories that I didn’t have access to as a child and teen, that I eventually found as an adult. I still needed those stories, as a 20-something-year-old, because the inner kid in me never got to see themself. People are hard at work to ensure that young people today get access to the books as they deserve, but I think there are still many adults across the nation that are needing and seeking MG and YA books about queer identity, too, to give their inner kids the stories they needed when they were young, too. And, when education and empathy wins over book bans and censorship, young people will need your books to be ready, waiting for them on the shelves.