Works of Justice is an online series that features content connected to the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program, reflecting on the relationship between writing and incarceration, and presenting challenging conversations about criminal justice in the United States.

In the United States, media coverage has centered the experience of Black men in public discourse on police reform, rightfully responding to the terror of brutality cases, ranging from Rodney King in 1991, to the more recent series of murders that propelled the Black Lives Matter movement. But a piece of the conversation is missing. Though women of color have been at the center of protests against state violence—as mothers, daughters, and sisters—women’s direct encounters with police brutality remain largely underreported and unseen.

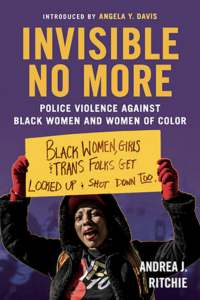

Andrea J. Ritchie is a police misconduct attorney and advocate for women of color and LGBTQ women of color who have been victims of police violence. As a Researcher-in-Residence on Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Criminalization at Barnard College and the author of Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color (Beacon Press, 2017), Ritchie stresses that viewing police violence solely through a male lens stops the conversation short. What is the first step in addressing the rampant sexual harassment and state violence against women of color and gender nonconforming people? Community stakeholders and justice advocates must become aware of their own complicity in the problem.

Andrea J. Ritchie is a police misconduct attorney and advocate for women of color and LGBTQ women of color who have been victims of police violence. As a Researcher-in-Residence on Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Criminalization at Barnard College and the author of Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color (Beacon Press, 2017), Ritchie stresses that viewing police violence solely through a male lens stops the conversation short. What is the first step in addressing the rampant sexual harassment and state violence against women of color and gender nonconforming people? Community stakeholders and justice advocates must become aware of their own complicity in the problem.

Ritchie is not afraid of these challenging conversations. In this interview with Giselle Robledo, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program intern, Ritchie exposes the societal costs of criminalizing immigrant women and Muslim women—groups targeted by state violence and media misrepresentation—and how cases like Sandra Bland’s became crucial in creating a more public dialogue around violence against women of color. Ritchie’s profound scholarship both deconstructs preconceived notions about who police violence affects, and constructs a powerful and cogent history that informs how communities can reduce the impact of state policing and violence. For Ritchie, the answer is not easy, and she argues for a solution that lies beyond oversimplified proposals for police reform.

As Angela Y. Davis writes in the foreword to Invisible No More: “She does not urge us simply to add women of color to the list of targets of police violence—a list that is already longer than anyone would wish. She asks us to consider what the vast problem of state violence looks like if we acknowledge how gender and sexuality, disability, and nation are intermeshed with race and class.”

We are excited to host Andrea J. Ritchie as our moderator in our May 11 World Voices Festival event, A Question of Justice, that features a roster of New York City-based criminal justice reform experts, alongside our Writing for Justice fellows. RSVP for this free event at the Center For Social Innovation here.

Writing For Justice Fellowship applications are open until 11:59pm EST on May 15, 2019. We invite you to apply.

GISELLE ROBLEDO: Your work reveals how little reporting we have about police violence and women of color, and offers the pivotal case of Sandra Bland’s death as an example of violence against women being brought to public consciousness on a mass scale. Can you tell us more about what drove you to write Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color?

ANDREA J. RITCHIE: Invisible No More is based on my experiences over the past two decades as a Black lesbian immigrant survivor, organizer, researcher, and advocate in movements against gender-based violence and police violence. As a young person becoming engaged in the women’s movement and movements against police violence following the non-indictment of the officers who beat Rodney King in the early 1990s, I was perplexed by the ways the experiences of Black women who were shot, beaten, sexually assaulted, and publicly strip-searched by police were absent from conversations in both movements—why weren’t these stories perceived as police violence or gender-based violence when they were clearly instances of both?

ANDREA J. RITCHIE: Invisible No More is based on my experiences over the past two decades as a Black lesbian immigrant survivor, organizer, researcher, and advocate in movements against gender-based violence and police violence. As a young person becoming engaged in the women’s movement and movements against police violence following the non-indictment of the officers who beat Rodney King in the early 1990s, I was perplexed by the ways the experiences of Black women who were shot, beaten, sexually assaulted, and publicly strip-searched by police were absent from conversations in both movements—why weren’t these stories perceived as police violence or gender-based violence when they were clearly instances of both?

My frustration only increased over the years—why were instances of police violence against women and LGBTQ folks of color rarely even mentioned in mainstream discourse, even when they took place right before our eyes, often in the same ways and even around the same time as incidents targeting men of color which garnered national and even international attention, even as women and LGBTQ people of color were consistently organizing and calling for action? Why were we only talking about and organizing at a national level around Amadou Diallo’s murder by New York City police when young Black women like Tyisha Miller and LaTanya Haggerty were shot down the very same year in circumstances that were quite similar in terms of number of shots fired or officers’ claims to have mistaken a cellphone or a wallet for a gun? Why was Abner Louima’s brutal rape by NYPD officers the only example of sexualized violence by police most people could call to mind until recently, when it is systemically experienced by women and LGBTQ people of color every day? Why didn’t Michelle Cusseaux, a Black lesbian who was killed by Phoenix police just a few days after Mike Brown, by an officer who claimed, like Mike Brown’s killer, that somehow the “look” in her eyes posed a deadly threat, become a national icon of resistance to police violence in the same way? Why wasn’t Mya Hall, a Black trans woman killed by police just a few weeks before Freddie Gray, also at the center of the Baltimore uprising?

And, in spite of explicit calls to action on police violence against women from generations of women of color, from Ida B. Wells to leaders of the civil rights movement, to Angela Y. Davis, to INCITE!, why has the anti-violence movement remained strikingly silent about these forms of violence against women? Why, even when people did know the stories, were they not driving our analysis of the issues and responses?

Invisible No More represents an effort to answer these questions, and then ask more—about how placing policing, criminalization of Black women, Indigenous women, and women of color at the center of both conversations shifts and expands our analysis and demands, as well as our overall visions of safety and the means we devote to achieving it.

The title is a statement of fact, a demand, and an aspiration. In 2015, following Dajerria Becton’s videotaped assault by a police officer at a Texas pool party, Sandra Bland’s death in police custody in the midst of a summer of police violence and resistance, a teen’s violent arrest in her classroom in Columbus, South Carolina, and the publication of Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women, a report I coauthored with Kimberlé Crenshaw of the African American Policy Forum, it would seem we turned a corner, at least in terms of recognition that Black women and girls are also targets of police violence. And still, we have yet to move beyond visibility—mainstream discussions, advocacy efforts, and policy change around police violence and gender-based violence still largely don’t specifically address women’s experiences, even if there is a token mention of Sandra Bland’s name.

Invisible No More represents my best effort to summarize my own efforts and those of countless other women and LGBTQ people of color over many decades to change that, in the hopes that it will serve as a resource to survivors, organizers, and advocates seeking to expand our understanding of the many forms police and gender-based violence take, and deepen our demands for safety.

ROBLEDO: Community led counsels, such as the Civilian Police Review Board recommended in Ann Arbor after Aura Rosser’s death, have been elevated as a potential solution to police violence, purported to “strengthen trust in the police.” I’d love to hear your response to this. Does the idea hold any merit, or is it a deviance from the search for true justice?

RITCHIE: I don’t think strengthening trust in the police is the goal given that police were created and continue to be mandated and encouraged to surveil, contain, control, and punish Black people, Indigenous people, migrants, disabled people, gender nonconforming people, low-income people, and people surviving through informal economies—it would be counterintuitive to what we know, and to our survival.

The goal is to end police violence—and ensure accountability and repair when it happens. Civilian oversight can serve an important function toward this goal, but only if there is real power and resources to independently investigate and discipline officers, and to make real systemic changes to how departments operate. And ultimately, their effectiveness is limited by the fact that they only come into play after the harm is already done, and rarely take action to prevent or end the violence that is attendant to policing. Additionally, most civilian oversight bodies are at the mercy of mayoral funding and control—and the mayor oversees the head of the police department, so there is often a close relationship there. And there is considerable resistance to independent investigations and disciplinary authority on the part of police unions—for example, they recently sued to prevent New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board from even being able to investigate police sexual violence, and blocked a bill that would allow the civilian oversight agency in Chicago to do so as well. Often union contracts limit or undermine even the disciplinary authority of police management, much less civilian oversight bodies.

Ultimately, while we fight for greater and more consistent accountability for officers who harm individuals and for systemic changes to prevent future harm, it is also essential to consider how we can shrink and eventually eliminate the role of policing and punishment in our communities altogether, and instead invest our energies and resources into developing transformative approaches to harm, poverty and structural economic oppression and exclusion, and public health that will actually increase safety and well-being for all members of our communities.

“The goal is to end police violence—and ensure accountability and repair when it happens.”

ROBLEDO: Your writing sheds light on how structural racism specifically affects women of color, where encounters with police often result in police violence. What are some steps and actions that communities can take to reduce the criminalization of women of color?

RITCHIE: There are so many potential points of entry. The most important is to challenge criminalizing narratives which shape how both police and members of the public view and respond to the presence and bodies of women and gender nonconforming people of color as a racially gendered, sexualized threat that must be contained and controlled as inherently disorderly, deviant, deceptive, and inviolable, undeserving of safety or self-defense. The Invisible No More study guide offers tools for self-reflection and everyday conversations uncovering and challenging the operation of the stories we tell and internalize about women of color which drive incidents like the one that resulted in Sandra Bland’s death, the constant violent policing of Black women’s presence and protest of mistreatment in public spaces, and the daily violations of countless Black women and women of color by law enforcement agents.

Another is to support decriminalization campaigns under way across the country targeting offenses women of color are most frequently charged with—like efforts to decriminalize drug use, possession, and sale, DecrimNY and DecrimNOW, working toward decriminalization of prostitution in New York and Washington, D.C., and efforts to end “broken windows” policing of “public order” and poverty-related offenses, as well as campaigns to free survivors of violence who are criminalized for defending themselves or their families. At Interrupting Criminalization: Research in Action, we are working to identify the top points of contact and criminalization for women and gender nonconforming people so that we can support campaigns that are working to stop police interactions before they start.

We are coming up on the third annual Black Mamas Bailout action, an incredibly successful initiative launched by Southerners on New Ground and the Movement for Black Lives, to free and call attention to the ways and reasons Black women like Sandra Bland are arrested and held in jails across the country for no reason other than the fact that they cannot afford to buy their freedom. If people do nothing else after reading this, I invite them to make a contribution to freeing Black mamas—80 percent of women incarcerated in local jails are mothers, most of them of minor children, most serving as the primary caregiver at the time of arrest, many of whom will lose custody of their children as a result of prolonged detention, many of whom were arrested for simply taking things they needed for themselves and their families.

Finally, people can push themselves, their communities, policymakers, and legislators to break our reliance on police and criminalization as the default response to every harm and need—from domestic violence to unmet mental health needs to child welfare to homelessness to unemployment to schoolyard taunts. In each of these contexts and more, girls, women, and gender nonconforming people of color are all too often criminalized and subject to violence at the hands of law enforcement instead of receiving the support and resources they need to not only survive, but thrive. Instead of pouring more and more resources into policing, criminalization, and punishment—whatever form it takes, be it cages, electronic monitoring or separating children from their families instead of providing resources and support for families—we need to invest in housing, education, living wage jobs, and community-based programs rooted in true safety, transformative justice, and accountability.

“. . . girls, women, and gender nonconforming people of color are all too often criminalized and subject to violence at the hands of law enforcement instead of receiving the support and resources they need to not only survive, but thrive.”

ROBLEDO: The United States has exploded with media reports of increased anti-immigration sentiments and Islamophobia. Can you connect violence at the border and the treatment of Muslim women to the ideas in your book, Invisible No More?

RITCHIE: The third chapter of Invisible No More highlights how migrant women and gender nonconforming people of color, including Muslim women and gender nonconforming people, have been targets of exclusion, violence at the border, and discriminatory policing and punishment within the United States throughout history, beginning with the first immigration law, the Page Act of 1875, which banned anyone who has ever—or is perceived to have—engaged in prostitution. The law was deployed almost exclusively to exclude Asian women migrants at the border and violently police them in the interior, and remains on the books to this day.

Invisible No More traces the ways in which the border has literally been etched on the bodies of migrant women through rape, sexual extortion, physical violence, and family separation, and continues to be through laws and policies that are only intensifying in the current political climate. It also highlights the hidden stories and criminalizing narratives of Muslim women and girls who have been targets of the “war on terror” since it was launched in its most recent iteration post-9/11.

Invisible No More’s urgent call to bring the unique experiences of women and gender nonconforming migrants of color to the center of our discourse or resistance is only more timely and critical in the current moment.

ROBLEDO: Anna Chambers’s case has brought to light how widespread the issue of abuses by law enforcement is, propelling legislation eliminating the consent defense for law enforcement officers accused of sexually assaulting someone in police custody. Under laws such as this, uncoerced sex in police custody does not exist; it is always considered rape. In your opinion, is this legislation an adequate response? What does real accountability look like—and is community reconciliation in this context possible?

RITCHIE: Absolutely not.

Laws prohibiting officers accused of sexually assaulting people in their custody from claiming consent of the survivor as a defense in criminal prosecutions reach only the tiniest sliver of cases, the vast majority of which will never be reported, never be believed, never be deemed worthy of investigation, discipline, or accountability of any sort, much less result in a prosecution of any kind, including one in which the accused officer will claim consent. In fact, the BuzzFeed coverage which propelled much of this legislation itself acknowledges that it would have changed the outcome in only 26 cases over a dozen years, a tiny fraction of the hundreds that have come to light over that time frame.

Additionally, such laws only apply when an individual is in the custody of law enforcement, and therefore don’t reach the vast majority of situations in which police sexual violence takes place: during traffic stops, domestic violence and sexual assault investigations, responses to calls for help, and when law enforcement officers engage with youth through civic engagement programs and while policing schools.

And they do absolutely nothing to prevent sexual assaults by law enforcement agents from happening in the first place—the majority of the nation’s top 35 police departments don’t even have a policy in place prohibiting officers from engaging in sexual conduct when on duty, or using service weapons, patrol cars, government facilities or databases, or simply the authority of the badge, to force or extort sex, whether on or off duty. Mandating departments to adopt and effectively enforce such a ban would be a critical step in the right direction.

Finally, removing police from schools and reducing their presence and power in other spaces where they are targeting survivors is a much more effective approach to addressing sexual harassment, extortion, and violence by law enforcement than eliminating a defense in criminal proceedings which are relatively rare because officers deliberately target people they think will not be believed, or who are vulnerable to retaliation, deportation, or criminalization.

ROBLEDO: What books or essays would be essential readings for a syllabus on violence against women of color?

RITCHIE: There are SO many—can we limit it to 10 and focus on police violence, or I am going to miss a lot and get in trouble with everybody! Everything by Angela Y. Davis; everything by Beth E. Richie; everything by Mariame Kaba (blogging at usprisonculture.com and tweeting at @prisonculture); the INCITE! Color of Violence anthology; Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins; No Mercy Here by Sarah Haley; Chained in Silence by Talitha LeFlouria; PushOUT by Monique Morris; Subnini Ammanna’s The Pedagogy of Pathologization; TESTIFY by Simone Johns; Robyn Maynard’s Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present; Trap Door, edited by Tourmaline, Eric Stanley, and Johanna Burton; a law review article by [PEN America Writing For Justice Fellow] Priscilla Ocen about policing Black women in public housing, there’s also a recent special issue of Souls on police and carceral violence against Black women. There’s a list of resources on the invisiblenomorebook.com website too. There’s SO MUCH MORE!

Audio

A Question of Justice – a PEN America World Voices Festival Event

The Lit Review Podcast – Invisible No More with Andrea Ritchie