Banned in the USA Q&A: Varian Johnson asks if book bans are meant to ‘keep a certain population of our country down’

Varian Johnson has a hard time understanding why books about segregation or the effects of racism are troubling for some people.

“I like to say, if my ancestors can live in the experience, your ancestors can read about it, at the least,” he told PEN America.

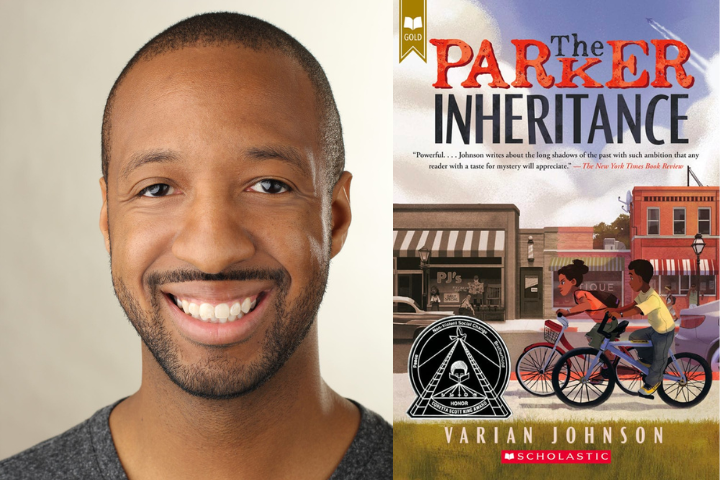

Johnson’s middle-grade novel The Parker Inheritance, a puzzle mystery that touches on the legacy of racism, was banned twice in the 2021-2022 school year, according to PEN America’s Index of Banned Books. Two of his other books, My Life as a Rhombus and What Were the Negro Leagues? were each banned once.

Johnson dismisses the notion that banning a book is a badge of honor for an author, something that might boost sales, which says happens “a very, very, very small percentage of the time.” More often, he said, removals go unknown, or become “a soft ban” that takes a book out of circulation.

“It’s about the young people losing access to a book that may feature someone who looks like them or may explore a world that they want to know more about or even have questions about. They are the losers in all of this. So even if one out of 100 authors does financially well—and again, I’m not convinced that’s true—at the end, everyone loses out.”

Johnson talked to PEN America about getting caught up in the book banning frenzy.

PEN America: What was your first experience with challenges to your books?

Varian Johnson: I remember my first real experience was going to a school, being invited to speak to a school. And when I got there, I was asked not to speak about this certain book. And I was like, “But that’s why you brought me here.” And that was a really jarring experience. And since then, I’ve seen it just magnify and multiply from having books removed from state-sanctioned or district-sanctioned lists, or being removed from libraries, or being placed behind the librarian’s desk where you have to ask for permission to read it.

What do you think is driving these actions?

I think there’s so much fear about race right now. Folks love to throw around this “critical race theory” term, and most of those folks don’t really know what it means. We’re just teaching history or a different side of history that may not have been shown. We have many, many books that talk about racism from a white perspective, from the white gaze. You know, To Kill a Mockingbird is a great example. It’s a wonderful book, but it only tells one side of the story. And I think many folks will pat themselves on the back because they read this one version of a book and they feel like they understand race and we’ve discussed it all. But there are so many other books to read that show different circumstances of it, and you don’t have to be afraid. They don’t want their children to feel bad. And I just don’t understand the concept of this. Books are such a safe place to discuss and to explore all these things as opposed to like the real world in real time.

What would you say to somebody who thinks one of your books is inappropriate?

I just want them to read the book first and think about, why is it inappropriate? And then I’d ask them to think about, are you saying it’s “inappropriate” for all children or your children? You know, I think a parent has the right to say what may or may not work for their child. I can respect that. But what gives you the right to bar all children from reading it? To bar all children from seeing a life that imitates theirs. It bars them from seeing someone who looks like them exist on the page and triumph over something.

I don’t know if folks really realize what they’re doing when they’re doing book bans, and the effect that it has. Folks will say banning a book just influences one book, and that’s not true. It influences the book, but any potential reader for that book, right? It influences other books that are similar to that book that maybe a teacher or librarian is worried about, or that a community member will attack. It causes programs to be canceled, affecting more books, affecting more readers. It’s this trickling effect that kind of branches all the way out.

Most books that were banned last year featured a person of color or an LGBTQ character. What does that say to people with those identities?

Any time a book that features someone who looks like you is banned, it says that you’re not worthy. You don’t deserve to exist. Right? Your life is not important. That’s wrong and it’s dangerous. It causes kids to second guess their opinion. It causes them to second guess who they are, who they want to be, how they look, who they love, to fit into some idea of what’s normal. And normal is extremely subjective.

Some people say, oh, they can just go buy it at the bookstore if they want it.

This is a very privileged thing for someone to say, well, they can just go buy it. No, they can’t. Not every community has a bookstore. Not everyone has money to spend on books. That’s one of the reasons the library exists, right? By banning books and by dismantling the power of libraries, we are creating a bigger gap, a socioeconomic gap, I would say. Sometimes I feel like that’s on purpose. You know, this idea that if we hide facts, if we exacerbate fear, it will keep a certain population of our country down and raise other parts of it. And that’s not good for anyone. That’s very, very dangerous.

Varian Johnson is the author of novels for children and young adults including Playing the Cards You’re Dealt, which was an ALA Notable Children’s Book and Kirkus Reviews, Publishers Weekly and Booklist best book of 2021, and The Parker Inheritance, which won a Coretta Scott King Honor award. He co-created with Shannon Wright the graphic novel Twins.

Varian Johnson is the author of novels for children and young adults including Playing the Cards You’re Dealt, which was an ALA Notable Children’s Book and Kirkus Reviews, Publishers Weekly and Booklist best book of 2021, and The Parker Inheritance, which won a Coretta Scott King Honor award. He co-created with Shannon Wright the graphic novel Twins.

PEN America is committed to defending the Freedom to Read. To learn more about PEN America’s efforts, click here. The PEN Children’s and Young Adult Books Committee also fights book bans and supports Children’s & YA authors. Learn more about the committee here.