Laura Benitez contributed research to this blog post.

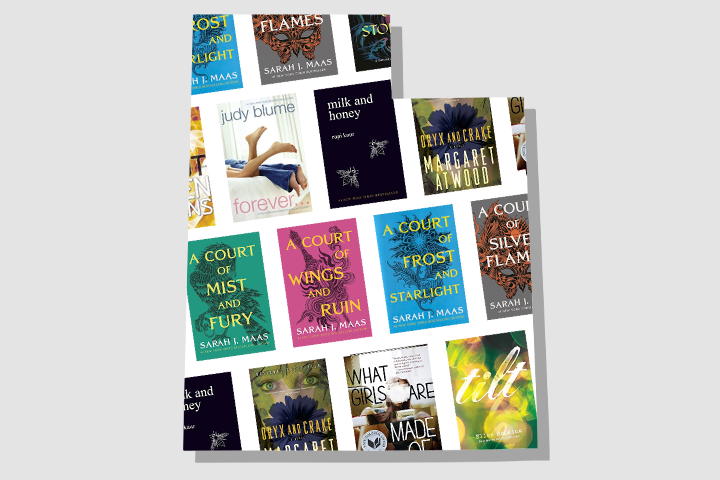

Earlier this month, Utah’s State Board of Education released a list of 13 books to be banned in every public school across the state. The “No-Read List” list includes popular titles such as Forever… by Judy Blume, Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur, and A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas.

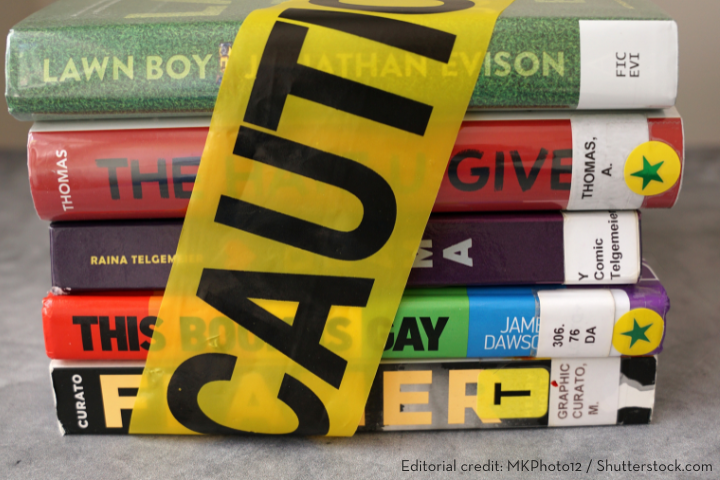

The list was a result of the state’s HB 29, which was signed into law in March despite public outcry and persistent campaigning from librarians, teachers, students, public school advocates, and free expression experts, including PEN America. The law has now opened the floodgates for mass bans across Utah, and also requires schools to “dispose” of any banned books from their libraries.

HB 29 created an environment of fear across Utah schools. But even before the law came into effect, schools were already pulling books from shelves.

The 101 on HB 29

HB 29 is one of the most extreme book banning laws currently in effect. The law mandates statewide bans, and has resulted in the first instance of a state releasing an official list of books that are illegal to stock on school shelves.

The law builds on 2022’s HB 374, aka the “Sensitive Materials in Schools” Act. HB 374 banned so-called “sensitive materials” from public schools, which it defined as “indecent or pornographic” materials under existing state statute. The law caused school book bans in Utah to jump from just 12 in the 2021-2022 school year to 281 the next; it was used to justify the bans of popular titles like Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult, The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, and Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez.

Even that wasn’t enough for legislators: the bill’s author, Utah’s Rep. Ken Ivory (R), said that this year’s HB 29 was needed to bring clarity to school districts and “uniformity across the state.” The bill also adds extreme new measures–and still contains unclear language.

Utah has 41 school districts and more than 100 charter schools. Under HB 29, a book that is banned for containing “objective sensitive material” at three school districts (or two districts plus 5 charter schools), will be subject to removal across the other 39 districts and every charter school, affecting over 670,000 public school students. In other words, once less than 10% of districts deem a book “objective sensitive material,” the law makes it illegal for all public schools to stock it. In effect, HB 29 marks the end of local control over what kind of books are in a school library.

HB 29 has created a muddled set of definitions in an attempt to create a “bright line” between “objective” and “subjective” sensitive materials. “Objective” sensitive materials that meet the three-district threshold are banned statewide through Utah’s “No-Read List,” but “subjective” sensitive materials can be banned locally without triggering the statewide process.

However, the allegedly “bright line” simply adds more confusion: the definitions are both too vague and highly specific, and they also overlap.

To clarify the new rules for school districts, the Utah Board of Education has distributed a questionnaire. According to the law, if someone, like a parent or a student, plausibly alleges that a book is “sensitive,” it must be immediately removed from shelves pending investigation, counter to best practices. Then, the questionnaire is used to determine if the book is an “objective” sensitive material by asking if it contains a depiction or description of at least one of the following:

1) “human genitals in a state of sexual stimulation or arousal”

2) “acts of human masturbation, sexual intercourse, or sodomy” and/or

3) “fondling or other erotic touching of human genitals or [the] pubic region.”

The questionnaire is reflective of a decision flowchart created by the Board of Education that further tries to clarify the standards.

However, the confusion between what is “objective” versus “subjective” lies in the overlap. Both “subjective” and “objective” categories, for example, encompass materials that are “pornographic or indecent material” or “harmful to minors” under state statute.

According to the flowchart, something should be considered “subjective” only if it does not fall into one of the three “objective” categories above, but still contains some level of sexual content and “when taken as a whole, has no serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” But this contradicts other portions of the bill. The law attempts to have its cake and eat it too: it allows districts to determine the literary value of a “subjective” sensitive material, but it also explicitly instructs districts to “prioritize protecting children from the harmful effects of illicit pornography over other considerations in evaluating instructional material.” By prioritizing banning the undefined “illicit pornography” at all costs, librarians are discouraged from judging works on their literary merit, just their sex-related content.

Community members can also report a district to the state if they fail to properly navigate the new rules, and the state will audit districts for compliance by 2028. Further, in November, the state’s legislative counsel said that, “regardless of whether the board takes a vote and determines that something … doesn’t violate these pornography standards, that doesn’t foreclose the possibility that a prosecutor could bring charges against someone.” This law, with its unclear definitions and looming threat of enforcement, is a recipe for overcompliance.

Targeting of sexual content

The law goes above and beyond to remove sex-related content from libraries without concern for the overall value of the work; in fact, the law attempts to justify itself with an existing statute that says any “description or depiction of illicit sex or sexual immorality,” including the type found in its definition of “objective” sensitive material, has “no serious value for minors.” This is an attempt to circumvent the existing standards for obscenity, known as the Miller test. This standard, a version of which has been adopted by most states–including Utah–in their definitions of what is obscene, harmful to minors, or pornographic, allows for books and art to contain sex-related material and nudity without being censored. Take, for instance, Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut or The Fault in Our Stars by John Green – both of which contain sexual content but neither of which could be construed as pornographic (although both have nevertheless been banned in schools across the country).

Utah legislators’ zeal to “protect youth from the public health crisis of pornography” functionally requires districts to overcorrect and ban any sex-related content whatsoever. The tool is a blunt one; definitions of “sensitive materials” and thus “pornography” are expanded to include nudity, sexual content, and even sexual violence. In wholly defining this content as “pornography,” HB 29 threatens to ban swaths of literature – including some that may be a lifeline to students experiencing abuse.

All 13 of the books banned statewide in Utah thus far include descriptions or mentions of consent, healthy and unhealthy relationships, sexual violence, or abuse. The state of Utah has argued that their efforts will protect students from “exploitation.” But as authors and experts on sexual violence have testified, books for young people that feature or discuss sexual assault can, and are often designed to, help young people recognize dangerous situations, know when to reach out for help, or cope with trauma. Nevertheless, such titles are ripe to be banned in Utah under HB 29.

How we got here

This law, like HB 374, comes after years of advocacy from “parental rights” advocates in Utah. Utah Parents United, a well-funded advocacy group and PAC, has led the charge for the “parental rights” movement in Utah. They have been active in their push against sexually explicit content, including by developing a resource called LaVerna in the Library to support those seeking to ban books. Utah Parents United has been linked to multiple book bans in recent years.

In January, Rep. Ivory reposted Utah Parents United on Facebook. The group endorsed HB 29, and upon its signing in March, announced to its Facebook audience: “This is fantastic news as there is absolutely no reason not to support this bill.”

By allowing five charter schools to substitute one district in meeting the threshold of district bans, the state also opens the doors for charter schools to impose decisions on all public schools in the state, as long as two public districts also ban a certain book. Charter schools have different oversight systems than public schools and some have explicitly ideological missions or values. The executive director of a prominent charter school chain in Utah, for example, explained her approach: “I’m hoping to indoctrinate using truth and data. That Marxism and Socialism and Communism are bad and the free market is good. And we are unequivocal about that.”

Despite the difference in how they operate, under HB 29, decisions made at charter schools have the potential to influence what books remain on public school shelves.

More book bans on the horizon

HB 29 has resulted in the statewide ban of 13 titles, but more will undoubtedly be announced as they reach the thresholds detailed in the law: an official FAQ about the law’s rollout has described it as an “ongoing process.” As districts grapple with the finer points of the law and vague threats from some legislators of criminal liability, the impact is already being felt.

Ellen Hopkins, whose books Tilt and Fallout were among of the banned 13 titles, has described the “overwhelming” impact of her work being banned, and says that her work has always been about reaching students in need. “At the end of my books, there are resources for readers to go get help for the things that I’m writing about. So for me, my goal has always been to help young people make better choices,” Hopkins said. In a state where more than 14% of high schoolers have reported experiencing sexual violence, these resources are invaluable.

Under HB 29, those resources are now unavailable at public schools. Stories that could help students navigate unhealthy relationships, sexual violence, and other difficult experiences have been made illegal in a misguided quest to vanquish all sex-related content in books, making the library a less supportive place for students across Utah.

The full list of banned titles as of publication is below:

- What Girls are Made of by Elana K. Arnold

- Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

- Forever by Judy Blume

- Tilt by Ellen Hopkins

- Fallout by Ellen Hopkins

- Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur

- A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas

- A Court of Frost and Starlight by Sarah J. Maas

- A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas

- A Court of Silver Flames by Sarah J. Maas

- A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas

- Empire of Storms by Sarah J. Maas

- Blankets by Craig Thompson

To support advocacy against book bans in Utah, visit Let Utah Read.