The PEN Ten: An Interview with Silvia Moreno-Garcia

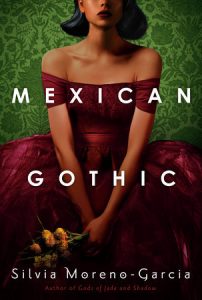

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Silvia Moreno-Garcia, author of Mexican Gothic (Del Rey, 2020).

Photo by Martin Dee

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

When I was a kid, I read a collection of short stories by Edgar Allan Poe, and it was my introduction to horror literature. Through Poe, I met H.P. Lovecraft, and I had such a longstanding relationship with his work that I went on to edit anthologies inspired by his stories and do a master’s degree that looked at eugenics and his writing. My great-grandmother couldn’t read or write, but she told me stories, and those oral narratives shaped me, too.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I look at my checking account. I know that sounds flippant, but I feel many times you’re not supposed to accept the material realities of working in the arts. I like writing, but I also like eating, so I’ve taught myself to write efficiently within the constraints of my life, which include a day job, a family, and stuff like that. The hard part is not inspiration. That’s easy. It’s the other stuff that takes a bit of juggling. But I tell writers who are starting out to figure out what their pace is like and stick to it. If you write 500 words a day Monday to Friday, you’ll have a short story in a few weeks.

“Read everything—nonfiction, fiction, memoirs, novellas, pulp, obscure stuff, the canon and the obscure. Writing is a constant conversation with yourself and with literature. You can’t have that if you’ve only tasted one dish.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Thomas P. Cullinan wrote three great novels beginning with the letter B: The Beguiled (1966), The Besieged (1970), and The Bedeviled (1978). I had to fish The Besieged from the vaults of my library. You just can’t find it in print. His other two novels have been recently reissued. The Besieged is what might be called a “potboiler.” It’s a multi-point of view novel where every point of view is unreliable. I wish more people would know Charles Williams, who was a great noir writer and has been oddly forgotten. And not enough of Rolo Diez’s work has been translated. He’s a wonderful noir writer, too. I think the only book available by him in English is Tequila Blue.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I read Tender is the Flesh, a prizewinning Argentinian novel about a world in which humans engage in cannibalism. You buy human meat at the butcher. Very dark and very interesting. Next, I’m reading A Judgement in Stone, which is a 1977 crime novel by Ruth Rendell about an illiterate maid, and The Silence of the Wilting Skin by Tlotlo Tsamaase, which has been described to me as a surrealist fantasy about a young African woman losing her identity.

5. What advice do you have for young writers?

Read everything—nonfiction, fiction, memoirs, novellas, pulp, obscure stuff, the canon and the obscure. Writing is a constant conversation with yourself and with literature. You can’t have that if you’ve only tasted one dish.

“Humans seem to love explaining the world through narratives. With many of my characters, I think one of the elements that unites them is that for good or ill, narratives shape them or have a great impact on them.”

6. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I think I’m obliged to say I’d like to reconstitute Lovecraft using his essential salts. I did my thesis work on him and feel in a strange way that I grew up with him. In a way, he was one of my best friends as an awkward kid growing up in Mexico City—which sounds bizarre, but it’s true. I don’t know, however, how the conversation might go. It would probably be very stilted. But for the most part, I’m like a turtle and don’t want to meet anyone, and I just want to live inside my safe, cozy shell. That’s why I like the internet. I can interact without having to let people see me. As for talking, I like to talk about books nobody knows about and old movies, so I’d probably show Lovecraft Get Out and Annihilation, and see what he thinks.

7. Why do you think people need stories?

Humans seem to love explaining the world through narratives. With many of my characters, I think one of the elements that unites them is that for good or ill, narratives shape them or have a great impact on them. In Gods of Jade and Shadow, my protagonist is on a quest while also understanding that this is a quest. And in Mexican Gothic, Noemí has read Gothic novels. I probably lived my entire youth through books and films. You know that line from “Iris”? “When everything feels like the movies.” Well, to me, everything felt like the movies. And the books.

8. Your recent novel is titled Mexican Gothic. On a surface level, it’s a simple and straightforward title. But titles are informative, providing a sense of what the book is about and creating an atmosphere for the reader. Yours does that, but it also seems stake a claim for its place in within literature, set apart from American Gothic, Southern Gothic, and the like. How did you decide on the title? What are the characteristics and themes of the Mexican Gothic, and why is it important to create a distinction?

8. Your recent novel is titled Mexican Gothic. On a surface level, it’s a simple and straightforward title. But titles are informative, providing a sense of what the book is about and creating an atmosphere for the reader. Yours does that, but it also seems stake a claim for its place in within literature, set apart from American Gothic, Southern Gothic, and the like. How did you decide on the title? What are the characteristics and themes of the Mexican Gothic, and why is it important to create a distinction?

Honestly, that was a placeholder title. I needed to call it something when I was beginning to write it. Originally, I was going to do an elaborate, metaphorical title inspired by the flowery titles of Mexican horror films by Carlos Enrique Taboada (Even the Wind is Afraid) or the giallos of the 1970s (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage). Eventually, I thought Mexican Gothic was a bit of an ironic title because this takes place on a town that was controlled by British forces. Hello, colonial legacy! Also, I thought Mexican Gothic was a mordant title because when you are Latin American, everything you write is called magic realist by default, and that’s the only thing you are allowed to write. I thought the title made it very clear that this is not magic realism and that we can write other stuff.

“Poor horror [as a genre] gets treated like the cousin we don’t talk about. He doesn’t get invited to dinner. . . But between possessed children and sewer mutants, there’s sometimes a space to touch on something special and no less poignant than a realistic drama. It’s the space of shadows on the wall that we stared at before we went to sleep when we were children and the frightful darkness around a campfire.”

9. For all the elements that shape the novel—vivid nightmares, dark twists, and curses—it’s the attention to mood and language that grips the reader as the story unravels and assists in making the aforementioned aspects affective. Can you speak briefly about the craft behind the suspense created in Mexican Gothic? How did you find its voice? Did the plot or characters come first? What was your experience in balancing the novel’s pace?

I had a 70/30 rule. For 70 percent of the book, things would go a bit slow and quiet, and then at the last 30 percent, all hell would break lose. I wanted that for two reasons. First, if you’ve ever gone into a haunted house, the person dressed as a monster doesn’t jump out at you when you walk in. You go through a couple of rooms, you see some skeletons and coffins, and then the person in the mask yells, “Boo!” You can’t create something suspenseful by dangling a ghost on every other page.

At the same time, gothic novels can get quite, um, gothic. By the end of classics such as The Monk, you’ve got a veritable collection of perversities. It adds up. I told my husband I wanted my heroine screaming for the last 30 percent of the book, and the readers screaming with her.

10. The novel, set in mid-century Mexico, not only utilizes the tools of gothic horror to unsettle and surprise the reader, but to also examine the worst and most fearful truths of society. In Mexican Gothic, this includes the racist ideologies and theories of eugenics. If we were to call this genre fiction, what are its inherent strengths? At its best, what can it reveal about society because of its specific rules and demands?

I love genre fiction, and I love horror. Poor horror gets treated like the cousin we don’t talk about. He doesn’t get invited to dinner. On the one hand, I joke that the industry that gave us Crabs: The Human Sacrifice—please look up the 1988 cover of that book—can’t be taken very seriously after going there. And the horror boom of the ’80s produced plenty of dreck. But between possessed children and sewer mutants, there’s sometimes a space to touch on something special and no less poignant than a realistic drama. It’s the space of shadows on the wall that we stared at before we went to sleep when we were children and the frightful darkness around a campfire.

Silvia Moreno-Garcia is the author of the novels Mexican Gothic, Gods of Jade and Shadow, Certain Dark Things, Untamed Shore, and a bunch of other books. She has also edited several anthologies, including the World Fantasy Award-winning She Walks in Shadows (a.k.a. Cthulhu’s Daughters).