The PEN Ten: An Interview with Mark Doty

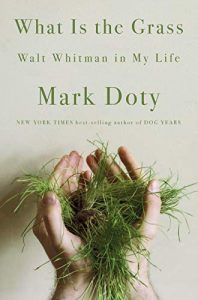

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Mark Doty, author of What Is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life (W. W. Norton & Company, 2020).

Photo by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I loved to read as a kid, and being completely absorbed in a book made me feel happy, hopeful, and safe. In third or fourth grade, I read a book—either one of those paperbacks you could order from Scholastic or from our school library at Whetmore Elementary in Tucson, Arizona—that broke my heart, the first one ever to do so. It was the story of two children whose cat would go wandering at night, and they tried to follow, but the nocturnal world shut them out. A helpful pharmacist gave them green liquid from a glass urn that allowed them to understand the speech of cats, so they followed their cat into the night, and learned that he was to become the King of Cats, and serve his kind. But he couldn’t do that and still be their cat, so they let him go, and drank from an urn of red medicine that returned them to the world of human speech. I cried mightily over that book, for the loss of the cat, for the loss of language, and for the ability to step out into the night and move between worlds. If anyone remembers that book, its title or author, I’d love to know about it!

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and art?

I’m on the side of fidelity to experience, in part because I think of writing as an act of inquiry, leaning against a remembered event or set of experiences in order to understand them more fully, perhaps to feel more fully present than I did the first time. But I know that faithfully representing how living feels often requires us to leave the inscription of facts behind for more evocative tools. Reading poetry (and even more so, writing it) teaches one quickly that the texture of subjectivity is more likely to happen when the writer turns to metaphor, digression, indirection, reflection, and pays attention to the body. Really any sort of technique that mimics how attention moves can bring us closer to how it feels to be an embodied, desiring perceiver. When I am writing, I believe I am telling the truth scrupulously, but later I often see that I’ve left things out, maybe changed the order of events, or made some image or object more important than it was at the time because it’s come to be metaphoric.

“Reading poetry (and even more so, writing it) teaches one quickly that the texture of subjectivity is more likely to happen when the writer turns to metaphor, digression, indirection, reflection, and pays attention to the body. Really any sort of technique that mimics how attention moves can bring us closer to how it feels to be an embodied, desiring perceiver.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

A sprawling, trackless mess of a landscape spread across my laptop, phone, notebooks, book margins, backs of envelopes. If you could track it, it would look like a web of connections—some clear and many subterranean. What momentum I have comes from the desire to get somewhere—to find in a mass of notes, quotations, and scribbled bits a form for something that weighs on me, something I feel compelled to explore. And, every once in a while, to finish something.

4. What is one book or poem you love that readers might not know about?

It’s been close to 40 years since the great New York poet James Schuyler won a Pulitzer for his masterwork, The Morning of the Poem, a book-length monologue spoken by a man whose body and emotional life are shattered as he’s recovering from a breakdown at his mother’s house upstate. It’s a poem of amazing tonal range: funny, acerbic, gossipy, full of longing, utterly heartbroken but sparked by wit and a sheer pleasure in the physical world that never deserts the speaker in this brilliant self-elegy. It’s one of the great American long poems. Deceptively casual, it doesn’t feel long at all.

5. Why do you think people need poems?

The reason why literature exists becomes so clear when you read a poem and find a named or given shape there for a perception, feeling, or thought you recognize—something that feels familiar even though you’ve never heard it named. It could be something quite small: the fragrant aura of cold around the sleeves and collar of someone who’s just come indoors on frigid day, the almost fluorescent blue of a gentian flower, the intensely present silence in the paintings of Vermeer. Those moments make the word larger, make us less alone. In some way, I’m not sure I can account for whether they make us more hopeful. Poetry constructs communities across space and time by showing us our common ground. And it reminds us that words are more than just little packages of information, thank god.

“Poetry constructs communities across space and time by showing us our common ground. And it reminds us that words are more than just little packages of information, thank god.”

6. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I’ve just been reading a terrific, surprising book of poems by Patrick Donnelly called Little-Known Operas, a great example of a poet opening his work to new risks and an engagingly idiosyncratic voice. It’s delightful to see a mature poet trying something new and succeeding brilliantly.

7. Aside from Walt Whitman, which poet, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Emily Dickinson! I don’t want to talk with her about anything in particular. I want to be in the presence of that extraordinary mind, and hear the tones in which she speaks. Her diction and syntax are so remarkably individual, so unexpected that I find she’s constantly revising my sense mid-poem of the tone in which she’s speaking. Earnest or sardonic? Simply questioning or skewering conventional thought? And here’s a plug, while I’m at it, for the marvelous recent film Wild Nights with Emily, based in part on the brilliant work of my friend Martha Nell Smith, a crucial Dickinson scholar.

8. Which poets working today are you most excited by?

Marie Howe, Ellen Bass, Brenda Hillman, Robert Hass, Louise Gluck, Frank Bidart, Tracy K. Smith, Brenda Shaughnessy, Gabrielle Calvocoressi, Jean Valentine, Tyehimba Jess, Ross Gay, Erika Meitner, Jericho Brown, James Hall, Mark Wunderlich, Monica Youn, Jane Hirshfield, and Dorianne Laux.

“I was aware of the beautiful swirl of text under the AIDS Memorial itself—it’s most of [Whitman’s poem] ‘Song of Myself’ . . . I stopped in the middle of the street because I realized what was parked there: The white trailer, longer than any truck you would usually see in Manhattan, with a large cooling unit and a covered ramp attached to it, was a temporary morgue. So, there I was, between the ennobled dead of the last great pandemic and the dead of this new one, who were falling so quickly there was no one to bury them.”

9. About Whitman, you write, “In a way that is true of no other great poet, his poems were a tool to make something happen; the change he wished to effect, and sometimes believed he could, was more important to him than art.” Do you consider Whitman’s poems a form of activism? How can poets affect resistance movements?

9. About Whitman, you write, “In a way that is true of no other great poet, his poems were a tool to make something happen; the change he wished to effect, and sometimes believed he could, was more important to him than art.” Do you consider Whitman’s poems a form of activism? How can poets affect resistance movements?

I think it’s fair to say that “Song of Myself,” “I Sing the Body Electric,” “The Sleepers,” and “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”—that is, a good chunk of Whitman’s best poems—represent a sort of spiritual activism; they are an assault on conventional ontology. They ask us to rethink our ideas of self and other, body and soul, of sexuality, desire, sin and moral authority, and of class and race. This rethinking has profound political and social consequences. He said later on that he wished he’d been an orator instead of a poet, as he would have reached more people. He was wrong about that; it’s just that poems work more slowly. In this country, we tend to think of poetry as enriching individual lives, but it’s useful to remember how Whitman’s work has been foundational for political and social movements in Spain, Latin America, and elsewhere.

10. Your work and life overlap with Whitman’s in multiple ways, including your appreciation for New York. You write, “New York pulls me up out of myself, just as it must have done for Whitman.” Your memoir came out in April, shortly after a governmental shutdown was emplaced in New York City due to COVID-19. Whitman, as you note, chronicled New York—from its rivers to its inhabitants. What language do you think Whitman would use to describe the city right now? As a poet, “another voice, another witness,” who has spent many years in New York, how are you processing the singularity of this moment?

It might more accurate to say that the singularity of this moment is processing me! I didn’t leave the city between March and yesterday, when I left for a two-week break up in the Hudson Valley. I didn’t understand how much I needed this escape until I was sitting in the passenger seat yesterday, my dearest friend driving, and felt as if the incredibly green canopy of leaves outside was literally pouring through me, I was so thirsty for it.

Whitman lived in New York before the Civil War and came of age during a time of social experimentation—a period when many believed people could live better lives—and sought out new ways to do so, from high-fiber diets to feminism, communal living to studying the Bhagavad Gita or phrenology. He had an unshakeable faith in the future, and a genuine belief that Americans could build a new democracy founded on mutual affection. But his experiences on the battlefields of Virginia and in the horrifying makeshift hospitals in D.C. challenged these hopes mightily. He never came back to live in New York, but I think if he had, we’d see something like the way he would have seen the city as it is now: humbled, often desolate, without its usual brass and bluster, and with the distinctions between those with resources and those without never more painfully clear.

The last few months are encapsulated for me in a single moment. I was walking my dog Ned around twilight at the top of the West Village. We came upon a memorial/demonstration for World AIDS Day in the new park across Seventh Avenue from the old St Vincent’s. People were standing in silence while the names of the lost were read. I was aware of the beautiful swirl of text under the AIDS Memorial itself—it’s most of “Song of Myself,” arranged by Jenny Holzer into a great spiral spreading out to occupy the pavement, in the middle of West 12th Street, between the memorial and the shining white emergency clinic north of it. I stopped in the middle of the street because I realized what was parked there: The white trailer, longer than any truck you would usually see in Manhattan, with a large cooling unit and a covered ramp attached to it, was a temporary morgue. So, there I was, between the ennobled dead of the last great pandemic and the dead of this new one, who were falling so quickly there was no one to bury them. And Ned and I passing through, somehow, returning home to shelter in place.

Mark Doty is the author of more than ten volumes of poetry and three memoirs: the New York Times-bestselling Dog Years, Firebird, and Heaven’s Coast, as well as a book about craft and criticism, The Art of Description: World into Word. He is a professor at Rutgers University and lives in New York City.