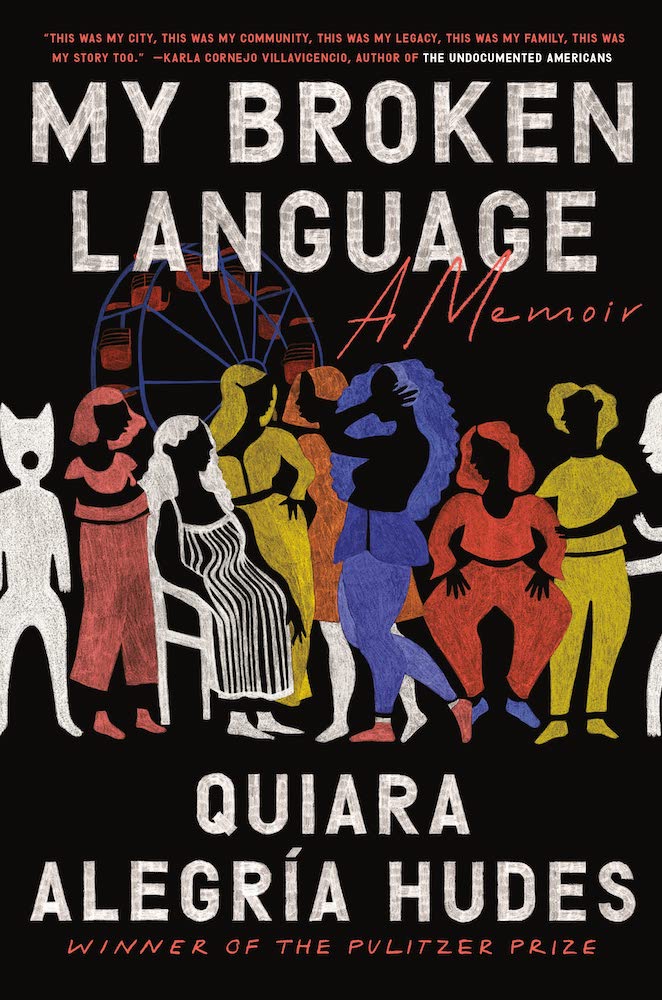

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Quiara Alegría Hudes, author of My Broken Language (One World, 2022) – Amazon, Bookshop.

1. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Writing is self-interrogation. Rigorous contemplation. That, in and of itself, is resistance in this capitalist amnesiac macho nation. No matter how clicky the banner ads, how triumphant the American history textbooks, and how magnitudinal the social media likes, the best writing exposes the loose screws in the scaffolding. See: bell hooks, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Toni Morrison.

2. Why do you think people need stories?

Bearing witness is the distinguishing act of being human. In 2003, I interviewed my Tío George about his service in the United States Marines in Vietnam. As a twenty-something artist, I worried I had no right to investigate the darkest corners of my elder’s life. Plus, it was accepted that él no habla de eso—he doesn’t talk about that stuff.

When the day came, we sat together over orange soda in plastic cups, and I asked one question: ”What year did you enlist?” After telling me—1966—he said, “It was hot, wet, cold, muddy, miserable.” For three hours he wept, chuckled, and described those traumatic tours. He was the cleanup crew, and yes that is both a euphemism and description for how war fields are cleared. Most of his emotional processing had happened through nightmares that continued to plague him.

“Writing is self-interrogation. Rigorous contemplation. That, in and of itself, is resistance in this capitalist amnesiac macho nation.”

George compared the Vietnamese countryside to his hometown in Puerto Rico. There was no need for follow-up questions—he told his tale with patient honesty, as if all he’d been waiting for was a designated space in which it was appropriate to talk about such intense things. The following week, I called to thank him but found myself on the receiving end of his gratitude: “I haven’t felt this light in 30 years,” he told me. It cemented my obsession with bearing witness.

3. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

When words like fat, bitch, witch, and welfare queen break your sister’s heart, or determine how and if your mother can safely walk her spiritual path, you learn the power of language pretty young.

The real power came when I repurposed and harnessed the word-borne shame. When I could gobble up all the slurs and slanders, then spit them back with love. Never in my adolescence did I think I’d use the word bitch or witch with love and pride. But here we are.

4. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

On the stage, I will go see any new play by Jackie Sibblies Drury, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Katori Hall, Amy Herzog, Annie Baker, Paula Vogel, and Branden Jacob Jenkins. They could adapt the phone book, and I’d pay full price or stand in the back. Just listing those names in succession thrills me.

On the page, I feel challenged by the complex humanity in Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s The Undocumented Americans, the rigor in Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy, and the circuitous structure of Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. I eagerly await new books by Esmeralda Santiago and Edward P. Jones.

“When words like fat, bitch, witch, and welfare queen break your sister’s heart, or determine how and if your mother can safely walk her spiritual path, you learn the power of language pretty young. The real power came when I repurposed and harnessed the word-borne shame. . . . Never in my adolescence did I think I’d use the word bitch or witch with love and pride. But here we are.”

5. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

Immense gratitude for angry, furious women who let it rip through their art, who embrace mayhem and whose work is a scream. On this first work day of 2022, I returned to my desk with my old copy of Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls, which I’ve been dog-earing and margin-scribbling in since 1999. Though there is much soothing verse in those pages, I think of it as a seismic rebellion, and I aspire to that level of poetic mutiny.

6. Some writers write with a specific reader in mind. This may be an individual, a group of people, a memory. Who or what do you envision as the reader, as you are writing?

If they’re jotting thoughts in the margins, in pen preferably, then they are my ideal reader.

As for the plays, Veterans for Peace led a series of frank and barebones talkbacks after Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue, my first play in New York. I realized I had written for them, and also for the parents who wept in fear because their own children were still serving in Iraq. More recently, I heard a group of active U.S. military service members stationed in the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea had read Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue around a table on a break. So maybe I wrote it for them? Will they be Veterans for Peace one day?

7. My Broken Language is a coming-of-age story steeped in themes of inherited wounds, family secrets, and finding one’s voice. Can you talk about the moment you decided that you would pursue this work as a book project?

7. My Broken Language is a coming-of-age story steeped in themes of inherited wounds, family secrets, and finding one’s voice. Can you talk about the moment you decided that you would pursue this work as a book project?

It springs from a joyous memory: July 4, 1991. Juan Luis Guerra’s seminal album Bachata Rosa had come out, and the memory of my stunning older cousins—all women—dancing to those merengue hits. . . . their bodies were sturdy, majestic, and diverse. All that physical celebration happened during a period of immense sorrow and loss for us—remember that 1991 was AIDS days, war on drugs days—and yet the vibes we surfed in the midst of grief. . . . that juxtaposition held the secret of life for me, so my investigation into our improbable joy became the memoir.

8. Toward the beginning of the book, you write about the origin of your name—“a name that broke its own rules,” as a joint testament to your Puerto Rican and Jewish backgrounds, as well as to invention anew. During childhood, you found the question of “What are you?” an understandably difficult one to answer. When did it start being easier to discuss the nuances of identity and difference? What was it like to write My Broken Language, and really explore these themes in depth?

Identity checkboxes are the antithesis of thorny, layered, funny writing. I have to head directly into the contradictions and mayhem, where no checkbox suffices. But luckily I can use words like a machete, to clear a path. More bramble always lies ahead, though.

There’s a moment in the book where I wonder if my very existence—Philly-born, half-white, Spanish-as-a-second-language—complicates my mom’s “brown Boricua” truth, being born and raised on the island as she was. And that’s the point where I’m like, “screw it, the identity litmus test reflects more on the tester than the tested.” Truth is: We’re here, receiving the ancestors’ bestowals, enjoying the wilderness for a breath, before we continue carving forward.

The musical notion of dissonance gave me vocabulary for this in high school. C-major and F-sharp major chords played simultaneously—that’s my identity. The beauty that births the clash.

“There’s a moment in the book where I wonder if my very existence—Philly-born, half-white, Spanish-as-a-second-language—complicates my mom’s ‘brown Boricua’ truth, being born and raised on the island as she was. And that’s the point where I’m like, ‘screw it, the identity litmus test reflects more on the tester than the tested.’ Truth is: We’re here, receiving the ancestors’ bestowals, enjoying the wilderness for a breath, before we continue carving forward.”

9. You’ve written plays, musicals, films, and essays, but this is your first memoir! Did it feel at all different to explicitly hone in your own personal life experiences?

Since I’ve always written out of family stories, the biggest difference for me is how books last. Theater is so ephemeral—it’s here and gone with very little time for word of mouth to spread. My book has margins, and people can write in them. That, to me, is the definition of making it. Seeing the finished product, I felt I had written a love letter to the future, and anyone who margin-scribbles is writing back.

10. Much of your work deals with inheritance. Who would you claim as ancestors in your literary genealogy? What do you hope to pass on to future writers who might claim you as theirs?

What a rush to feel held and also challenged by the work of so many forebears. Too many to list, but I will say that every day when I pray to ancestors, I name aloud Piri Thomas, Ntozake Shange, and James Baldwin. I also name Don Rappaport, a Philly composer who taught me music theory for free, and who told me a piece I had composed was better than Alexander Scriabin. Not that it’s a contest.

Mr. Rappaport’s in heaven now—I wonder if he’s ever joined Scriabin at the 88 keys and how their duet went.

Quiara Alegría Hudes is the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright of Water by the Spoonful and author of the memoir My Broken Language. She wrote the book for the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical In the Heights and later adapted it for the screen. Her notable essays include “High Tide of Heartbreak” in American Theatre magazine and “Corey Couldn’t Take It Anymore” in The Cut. As a prison reform activist, Hudes and her cousin founded Emancipated Stories, a platform where people behind bars can share one page of their life story with the world. She lives with her family in New York but frequently returns to her native Philadelphia.