The PEN Ten: An Interview with Nate Marshall

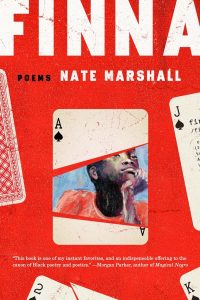

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Nate Marshall, author of Finna: Poems (One World, 2020).

Photo by Mercedes Zapata

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

As a kid, I loved biographies. I remember reading this biography of Crispus Attucks and being moved by his story and also baffled at how he wasn’t someone we learned about when discussing the American Revolution.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I write in spurts and fits. There are weeks where I produce poems by the handful and months where I write very little. I’m always looking for art, history, and culture to engage my mind with the faith that I will take those things back to the page when I’m ready. I don’t write every day, but I do try to do something in service of the work every day. Some days, that’s teaching. Most days, it’s reading, listening, and conversing. Some days, it’s writing answers to interviews ☺.

“Poets aren’t like a special class of people. We can march, food bank, and help in the ways any person can—regardless of our relationship to couplets and shit.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Lucy Negro, Redux by Caroline Randall Williams is a book of poems that I deeply admire and that I’ve taught from in the past. It was from a really small press—and so, I think was a bit overlooked—but I think it’s a book that had such an interesting engagement with Shakespeare, the Black literary tradition, and more.

4. How can poets affect resistance movements?

I think poets can be helpful to movements by bringing their talents to bear in service of individuals and organizations. Poets can participate in mutual aid, help write chants and other things, and donate books and poems in service of communities. Also, poets aren’t like a special class of people. We can march, food bank, and help in the ways any person can—regardless of our relationship to couplets and shit.

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I read mad things at once. A few in my recent/future pile are May We Forever Stand by Imani Perry, Black Minded: The Political Philosophy of Malcolm X by Michael Sawyer, Caste by Isabel Wilkerson, The Will to Change by bell hooks, and These Truths by Jill Lepore.

“At the moments of highest emotional resonance for us, we look toward poetic language to give us something to help encapsulate a large moment. I think that’s what we need poems for: to make the big moments in our lives smaller and make the small moments bigger.”

6. What advice do you have for young writers?

Read widely and far more than you write.

Read a good number of things you think you won’t like and try to identify what is working effectively in those things.

Try to commit to the work of noticing and self-reflection in all facets of your life.

Use social media for your literary engagement if it serves you, but try to ignore the petty beefs and spats and focus on the substantive conversations about craft and the sharing of work. And unplug whenever you feel it making you feel bad.

7. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I want to sit at the feet of Phillis Wheatley. I don’t think there’s a more important writer in the American tradition. I’d like to ask her what freedom meant to her and how it related to her work as a writer. I’d like to ask her what she remembered of her home and her kidnapping. I’d like to ask her what her real name was.

8. Why do you think people need poems?

I have often said people look toward poems when someone is getting married or buried. I take that to mean that at the moments of highest emotional resonance for us, we look toward poetic language to give us something to help encapsulate a large moment. I think that’s what we need poems for: to make the big moments in our lives smaller and make the small moments bigger.

“It’s not lost on me that part of people’s current investment in my book and in Black art more broadly is about our country’s political moment this summer. That means my success is inextricably linked to the murder of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and so many others.”

9. The poems in your new collection, Finna: Poems, are full of vigor. As gratifying as they are to read on the page, I couldn’t help but read them aloud so I could feel the rhythm and bounce on my tongue and hear the playfulness in my ears. In what ways did the Black oral tradition inform your writing? How did you approach capturing and celebrating Black lingua franca for this collection?

9. The poems in your new collection, Finna: Poems, are full of vigor. As gratifying as they are to read on the page, I couldn’t help but read them aloud so I could feel the rhythm and bounce on my tongue and hear the playfulness in my ears. In what ways did the Black oral tradition inform your writing? How did you approach capturing and celebrating Black lingua franca for this collection?

That’s such a big question. I’m as much a child of the oral tradition as I am of the literary tradition, if not more so. I came up immersed in hip-hop and Black folklore and history. My first relationship with language was via the ear, and so, it has an indelible mark on how I consider language. The final part of writing a book for me is a final edit where I read the whole book out loud in a single sitting to make sure it sits in my mouth right. I think of the book more as sheet music itself rather than as the fully realized song. It’s a tool you use to approach and interpret the poem, but it by itself isn’t fully the poem.

10. In a recent Twitter thread, you wrote that the book, Finna, “smiles how Black people smile”—a description I both loved and found perfect. I understand it, but I was hoping you could explain what you meant. How do Black people smile, why do Black people smile the way they smile, and how is it exemplified in your superb collection?

This book has already gotten a tremendous amount of attention, more than I imagined it would. I’m thankful and humbled by that, and I think it’s also a good example of this issue of the “smile.” It’s not lost on me that part of people’s current investment in my book and in Black art more broadly is about our country’s political moment this summer. That means my success is inextricably linked to the murder of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and so many others.

I think every moment of Black joy in this country is informed by a knowledge and backdrop of Black suffering and death in a way that we are just aware of and contending with, in ways other folks maybe don’t have to think about in their own lineage. Like, a Black wedding is in part a celebration—not only of the love of that couple, but it is also a celebration that the people marrying are at least in part descended from people who had no access to relationships that were respected by the power structure. That’s a different kind of smile, I think, than how other folks smile. When you know and really feel the impossibility of your survival and thriving, it just hits different when you get to celebrate.

Nate Marshall is an award-winning writer, rapper, educator, and editor. He is the author and editor of numerous works including Wild Hundreds and The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop. Marshall is a member of The Dark Noise Collective and co-directs Crescendo Literary. He is an assistant professor of English at Colorado College. He is from the South Side of Chicago.