The PEN Ten: An Interview with Jocelyn Nicole Johnson

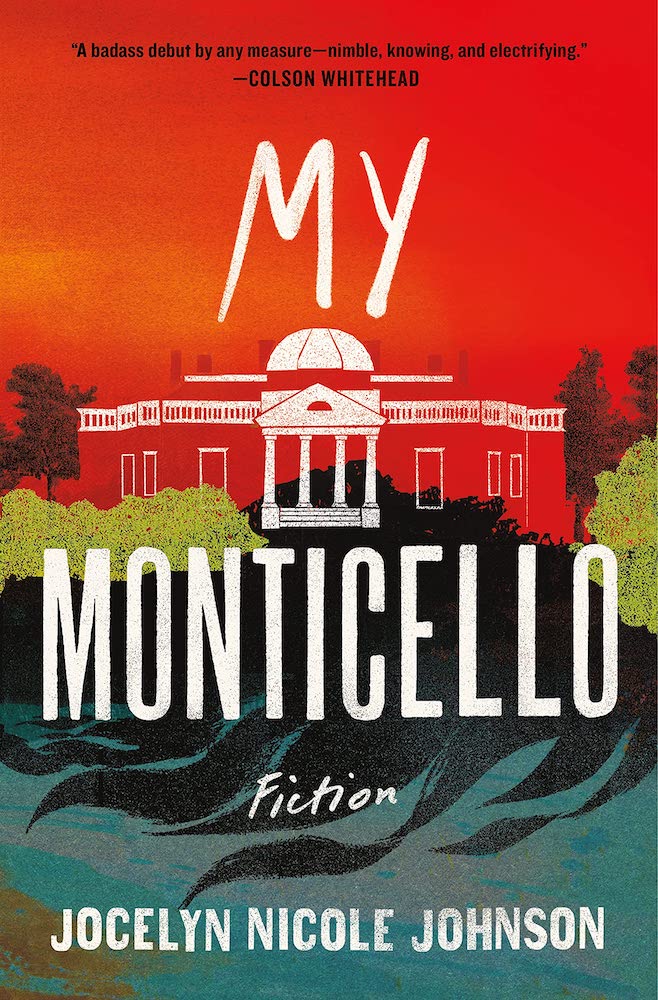

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Jocelyn Nicole Johnson, author of My Monticello (Henry Holt & Company, 2021) – Amazon, Bookshop.

Photo by Billy Hunt

1. Where was your favorite place to read as a child?

My childhood home had a finished basement with wall-to-wall carpeting, a sleeper sofa, and marigold walls onto which my big brother painted an enormous orange and brown design. That ’70s-styled room was my place for creative intake and output—for drawing, dancing, listening, and reading.

2. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

There was a constellation of childhood reading that shaped me, some of it campy, some of it fancy—my favorites were somewhere in the middle. At 13, I read S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, and learned that Hinton was a teenager herself when she wrote it. This inspired me to imagine myself as a writer. A few years later, I wrote my first novel.

3. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Fiction, for me, is a series of lies aimed at feeling true, or expressing something true. Some fiction gets at multiple truths, or the kind of contradictory truths that can exist in our real lives. In my stories, I often write in response to real incidents, but the people and places are inevitably upended on the page. In my stories, odd details push themselves forward, twisted motivations surface. Still I’m always trying to get at something true.

“The stories we are told, and the stories we tell ourselves, shape us in profound ways. They affect how we see ourselves and others, for good or for ill. They impact what we strive for, who we recognize as family, who we see as monsters, and where we call home. Stories can console us, or offer hope, in our despair.”

4. Why do you think people need stories?

I think that the stories we are told, and the stories we tell ourselves, shape us in profound ways. They affect how we see ourselves and others, for good or for ill. They impact what we strive for, who we recognize as family, who we see as monsters, and where we call home. Stories can console us, or offer hope, in our despair.

5. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

In high school, our class read Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. For some reason I was struck by this novel, its long and unfamiliar names, and rambling conversations. I loved how each character felt like a symbol, and the perversion of the protagonist’s predicament. How wonderful that a translated story can cross time and space to speak to 16-year-old me: a nerdy, artsy Black Virginia girl.

6. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

My parents hail from South Carolina, but I was born in Northern Virginia; went to college in the Shenandoah Valley; and taught visual arts in Virginia’s public schools in Harrisonburg, Arlington, and Charlottesville. The idea of place, and of my native state in particular, became the ground of the stories in my debut collection. I wrote about home and belonging using Virginia’s specific landscapes, emblems, and histories.

“When I’m writing, and especially in editing, I’m thinking about which words can be omitted. I look for where a word change might clarify, or else complicate the story in an interesting way. I’m thinking about the cadence of sentences, and what can lurk in the empty spaces.”

7. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I’d like to meet some future writer, someone who will write something that inspires and changes me. This writer will shift our current trajectory away from racism, extremism, inequity, and environmental emergency. It seems clear to me that some stories can motivate groups of people to perform harm. So it stands to reason that it is possible for stories to call us toward repair too. I want to meet, and talk with, and read, a writer who calls us—en masse—toward reparation.

8. Writers of short fiction often need to be more economical with their prose than longform fiction writers do. There’s more pressure on sentences and scenes in short stories to pack a punch! I was struck by a certain nimbleness in your quality of writing—your ability to move a story across time without needing many pages to do so. This was especially true in “Virginia is Not Your Home.” With that in mind, I was wondering, what are your criteria for crafting a stellar sentence? What do you think of first, craft-wise, when you’re about to write an important scene?

8. Writers of short fiction often need to be more economical with their prose than longform fiction writers do. There’s more pressure on sentences and scenes in short stories to pack a punch! I was struck by a certain nimbleness in your quality of writing—your ability to move a story across time without needing many pages to do so. This was especially true in “Virginia is Not Your Home.” With that in mind, I was wondering, what are your criteria for crafting a stellar sentence? What do you think of first, craft-wise, when you’re about to write an important scene?

I think, over time, the craft of writing gets absorbed into one’s body, through all the things we read, and what people tell us is “good writing.” As a teenager, I participated in Young Writers Workshop, a sleepaway camp that took place on the University of Virginia campus. My workshop focused on microfiction, and I was moved by the emphasis on brevity and compression—tendencies which have likely become a part of the bones of my ear.

When I’m writing, and especially in editing, I’m thinking about which words can be omitted. I look for where a word change might clarify, or else complicate the story in an interesting way. I’m thinking about the cadence of sentences, and what can lurk in the empty spaces.

“I am constantly cheerleading my young students to be brave and true. It’s scary to be true, even if you’re eight years old. It’s hard to trust that what you have to say, and your imperfect way of conveying it, are enough. But your experiences, your perspectives, are all you have. They will lead you to new, slightly different stories and ways of telling that are also yours. And they are absolutely enough.”

9. Throughout the story collection, your characters question fate and the truths and traumas they’ve inherited. They seek to persevere in an environment of national and personal unrest. Their days are burdened with the weight of the racism in the society around them. Of course, that world is—in so many ways—not unlike our own. Knowing this, how do you try to stay hopeful? What’s something, big or small, that makes you feel optimistic?

Hope for me is a way of being, in spite of these times and despite the heaviness of history. Hopefulness is probably part of my disposition, my inheritance from my parents, and their parents before them. I am hopeful because it allows me to get up in the morning and smile. I am hopeful because, right alongside our greed and violence, there are so many moments of care, of generosity, of learning, of kindness. I choose to recognize all of those moments of good work too, to celebrate them and root for them, even among so many troubling things.

10. Some people might not know that in addition to writing, you’re a longtime art teacher in Charlottesville public schools. What’s something, related to creativity and art making, that you always make sure to impart on your students?

So yes, I’ve taught visual arts, mostly to elementary-aged children, for 20 years in Virginia’s public schools. I am constantly cheerleading my young students to be brave and true. It’s scary to be true, even if you’re eight years old. It’s hard to trust that what you have to say, and your imperfect way of conveying it, are enough. But your experiences, your perspectives, are all you have. They will lead you to new, slightly different stories and ways of telling that are also yours. And they are absolutely enough.

Jocelyn Nicole Johnson is the author of My Monticello, five stories and a novella all set in Virginia, released by Henry Holt & Company on October 5, 2021, and selected by National Book Award winner Charles Yu as his most anticipated book for the year. Johnson has been a fellow at Tin House, Hedgebrook, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts; her writing has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Guernica, The Guardian, Kweli, Joyland, phoebe, Shenandoah, Prime Number Magazine, and elsewhere. Her short story “Control Negro” was anthologized in The Best American Short Stories 2018, guest edited by Roxane Gay, who called it “one hell of a story” and read live by LeVar Burton as part of PRI’s “Selected Shorts” series. A veteran public school art teacher, Johnson lives and writes in Charlottesville, VA.