The PEN Ten: An Interview with Linda Rui Feng

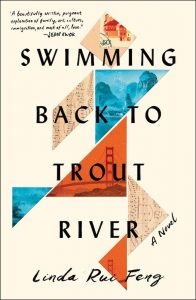

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Linda Rui Feng, author of Swimming Back to Trout River (Simon & Schuster, 2021).

Photo by Anastasia Brauer

1. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

Though I didn’t always grow up near bodies of water, in my writing I find myself drawn to rivers and coasts, probably because they gesture toward circulation and connectivity, and yet also have unique moods when observed on the time scale of days, years, decades, and even centuries.

For me, imagining or remembering a past is inevitably connected to a particular geography and place—it’s almost as if to move across time we need an anchor in space. My earliest memories are steeped in architectural interiors, such as the slant of a ceiling above where I took naps, the turn of a corridor that led to the outside—the way a window conducted light onto the floor. But later in my life, the spaces that excited me and stayed with me were routes and streams and city grids and alleyways with storytelling neighbors.

So perhaps our understanding of our world begins with small intimate places, and as we grow and extend our range and mobility and awareness, they begin to include larger units of space. And it is in this way that place becomes the ecological and psychic underpinning of our sense of self and how we tell our own stories, and it is this indelible sense of self I wanted to convey through the character of Junie at the beginning of my novel.

2. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

When I first began writing, I only put down what I was certain about—a sentence that comes into my head fully formed, or images and character traits that are relatively complete and insist on their own existence. This worked for a while, but of course I ran out of those certainties eventually, and I had to fashion what I could out of uncertainties and even bewilderment. Nowadays I’m learning to let the process of writing itself draw out the fragmentary and diffident sentence, to let it take its time and clarify what the hell happens to a character—before I have any clue.

“Perhaps our understanding of our world begins with small intimate places, and as we grow and extend our range and mobility and awareness, they begin to include larger units of space. And it is in this way that place becomes the ecological and psychic underpinning of our sense of self and how we tell our own stories, and it is this indelible sense of self I wanted to convey through the character of Junie at the beginning of my novel.”

3. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process, and how did you overcome it?

It’s so hard to choose just one! There were many moments when I wished that I could write more of “what I know” as the adage goes, to tap more directly into my own experiences and save time and energy fretting over whether I was getting something right. But as a writer, I’m drawn to what I don’t know, so I stubbornly want to inhabit lives unlike my own.

In one case, I got stuck writing about the youthful friendship and eventual fallout of two university students during the early ’60s in China, and in my desperation, I took a screenwriting class so I could reimagine the scene from a more cinematic angle. This forced me to move away from pure interiority, and it eventually got me out of that rut.

4. What is something that you feel your readers would find surprising about you?

I was terrible at using dictionaries back when they were hefty physical books, and I still feel a bit intimidated by their presence on bookshelves.

5. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

When I’m deep into a writing project, I tend to read more selfishly than I would otherwise, as I’m driven more by a need for problem solving than by curiosity. But by problem solving, I don’t mean that I read to find solutions for my writing. Rather, I seek out books that—somehow—produce a state of mind or a mental frequency in me that allows me to take in the content of the book yet simultaneously be alert to any snippets of insight that might make my draft better, that might answer a question about a character, that might move a storyline forward, etc.

“When I write fiction, I find that I’m often trying to chase down crucial though small moments of transformation in the lives of my characters, moments that would slip away unnoticed if it were not for a particular type of vigilance. I don’t think it’s a novelist’s job, per se, to make history ‘fresh’ or ‘relevant,’ but if she does her job well, her characters will inevitably illuminate an aspect of the past and throw open windows.”

Of course, there’s no way you can pick these books out from a lineup, so I read in small sips and see how it goes down. In most cases, what works best are books very different from what I’m working on—a manual of mycology, say, or something about fantasy careers I could be having if I weren’t struggling at my desk.

6. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

As someone who tries to produce a certain kind of experience for my readers through words, I love watching chefs at work and hearing them explain how they select and transform ingredients—some novel, some not—to create a series of unforgettable experiences with food, with culinary art. To witness this process is both humbling and inspiring. Two such artists come to mind (both featured on the series Chef’s Table): Dominique Crenn and the Buddhist nun Jeong Kwan, who cooks for her temple, the Baegyangsa, in South Korea.

7. Some readers might not know that in addition to writing fiction, you are a scholar and educator of Chinese cultural history. What is the relationship between history and literature for you? How do novelists make history fresh and relevant for today’s readers?

A colleague, the environmental historian Ling Zhang, was talking about how historians can relate to climate change, and she says brilliantly that historians—and especially those who study the more remote past—are “artists of remembrance.” I think that’s also a good way for me to connect what I do as a cultural historian inside the academy with what I do as a fiction writer.

When I write fiction, I find that I’m often trying to chase down crucial though small moments of transformation in the lives of my characters, moments that would slip away unnoticed if it were not for a particular type of vigilance. I don’t think it’s a novelist’s job, per se, to make history “fresh” or “relevant,” but if she does her job well, her characters will inevitably illuminate an aspect of the past and throw open windows.

8. An element of Swimming Back to Trout River that I was especially struck by was the way you played with time and pacing in the novel’s exposition. You often leave questions unanswered at a chapter’s conclusion and toggle between different characters’ storylines, in addition to reminding the reader as to what’s happening in the background by providing rich historical context. I’m curious as to how this structure figures into your writing and pre-writing processes. How did you balance historical research, plot development, and deciding how you were going to tell this story?

8. An element of Swimming Back to Trout River that I was especially struck by was the way you played with time and pacing in the novel’s exposition. You often leave questions unanswered at a chapter’s conclusion and toggle between different characters’ storylines, in addition to reminding the reader as to what’s happening in the background by providing rich historical context. I’m curious as to how this structure figures into your writing and pre-writing processes. How did you balance historical research, plot development, and deciding how you were going to tell this story?

It’s only in retrospect that I see what Tobias Wolff means when he said, “There’s no right way to tell all stories, only the right way to tell a particular story.” Much of the novel’s structure was improvised as it grew in fits and starts over many years, and I did research on historical events and topics as I needed to—without any system or even strategy.

It’s fair to say that at many points in the process, I felt like I wasn’t so much toggling but juggling—and often beyond my own capabilities. But I think this is all right—the novel as a form should be ambitious and a little messy, and should be larger and more capacious than its author. Of course the messiness was reined in by some constraints. What I felt sure about from the very beginning was that I never wanted one voice to dominate the story and its telling—I wanted to tease out the more obscure, individual microhistories from the larger looming historic events. I wanted the various voices to inform and complicate each other, and I also wanted to showcase how we revise the past as they recede from us in both time and space.

9. Swimming Back to Trout River is in many ways a nuanced retelling of the American Dream story. At one point, Momo thinks, “In America, without having to jostle for elbow room, every person, idea, and object had its place to exist.” This statement has an element of truth to it, but of course, America’s attitude toward immigrants is more complicated than this. In writing Momo and Cassia’s story, how did you feel their experiences most subverted the typical “American Dream” narrative?

Even in novels that don’t deal with the immigrant experience, the American dream narrative—from The Great Gatsby, say, to The Corrections—has been about the disillusionments that come from migrations through class, so this dream has constantly been dismantled and subverted. The stereotypical American dream narrative involving immigrants assumes that someone who has nothing to lose comes to America and gains (or regains) everything. This is a myth borne of hubris (about America and its virtues), as well as a flattening simplification of what immigration is and who immigrants are—and many excellent novels before mine have confronted this myth.

“The stereotypical American dream narrative involving immigrants assumes that someone who has nothing to lose comes to America and gains (or regains) everything. This is a myth borne of hubris. . . What I hope to show with characters like Momo is that the experience of emigration, however hopeful, involves a kind of sundering, a giving up of people and things that otherwise sustain them.”

What I hope to show with characters like Momo is that the experience of emigration, however hopeful, involves a kind of sundering, a giving up of people and things that otherwise sustain them. And because much of what they give up—the fabric of an extended family, rootedness to a place, an honest narrative of one’s own past—are wholly invisible, they often find it hard to articulate the shapes of these more wayward forms of grief.

When Momo voices that thought about America, he is voicing an optimism that often accompanies the leaving for an idealized “Elsewhere”—at that point in the story, he hasn’t yet experienced America’s distrust of people like him, who arrive from a communist country in the middle of the Cold War. (It was not uncommon for Chinese students in American universities to be followed and monitored, on and off campuses.) Nor has he experienced the ways in which racism and ostracism could lurk behind a smiling, “welcome-to-America” face. Within the scope of the novel, the character who feels this facet of America most keenly is probably Dawn, who in her music career, discovers that America is using her even as it ostensibly embraces her talents. But even before Momo confronts these problematic aspects of America, what he feels most keenly in his early days is a kind of vacuum, a thinness or even absence.

10. Music pulsates throughout the pages of Swimming Back to Trout River. What is your relationship to music? Did you listen to pieces referenced throughout the book, as you wrote about them?

By design, almost all the pieces of music in the book are fictitious—though I do wish that “The Waltz of the Hedgehog” existed!—because I want readers to encounter these pieces primarily through the lens of the characters and in the context of the story. When I wanted to get inside the head of, say, the character Dawn as she went busking on Fisherman’s Wharf, I listened to violin performances—but not as I was writing because it would’ve diverted my attention completely—and in particular those of Nathan Milstein, whose sound is utterly unique among violinists. Every time I hear his rendition of Sarasate’s “Introduction and Tarantelle,” I feel as astonished as if I’ve stumbled upon it for the first time.

Outside of a two-year stint in my high school’s orchestra, I’m an amateur listener of music—that is to say, a curious and attentive outsider who feels awe at its profound effects, rather than someone who is capable of devising and creating, or is able to fully explain such effects. Yet it is this sense of being on the outside of its mysteries that drives me to obsessively think and write about it, fighting tooth and nail to get at why it animates us and becomes a wellspring of complexity and contradictions and also, crucially, bewilderment. As someone whose primary tool is language, I’m also fascinated by the way the various arts push against each other’s boundaries and how they make incursions into each other’s territories.

Born in Shanghai, Linda Rui Feng has lived in San Francisco, New York, and Toronto. She is a graduate of Harvard University and Columbia University and is currently a professor of Chinese cultural history at the University of Toronto. She has been twice awarded a MacDowell Fellowship for her fiction, and her prose and poetry have appeared in journals such as The Fiddlehead, Kenyon Review, Santa Monica Review, and Washington Square Review. Swimming Back to Trout River is her first novel.