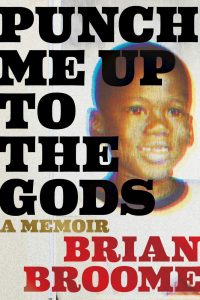

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Brian Broome, author of Punch Me Up to the Gods: A Memoir (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021).

1. Why do you think people need stories?

1. Why do you think people need stories?

Did you know that bees tell stories? I watch a lot of nature documentaries, and I watched one on bees that taught me that they will leave their hives in their drove in search of nectar. They’ll fly around looking for the best spots, the best fields of the kind of flowers they like to feast on. Sometimes they fly for miles, and when they get back, one bee will stand in the center of a multitude and do a little “dance.” In the dance, the bee will act out how it got to a specific field of bounty. It will show the other bees through its movements what actions they need to take in order to get to where it has just been. When I saw that, I thought to myself, “Bees tell stories.”

I think people need stories for the same reason. We need stories to show us the way—to give us guidance. Just as importantly, stories can feel almost like human contact, or at least connection—something I think a lot of us have been missing lately. After all, the power of narrative often lies in what we see in its characters and what we hope to see in ourselves. I have felt the power of this myself. I repeatedly miss busses because I’m so wrapped up in a page. And I’m better off for it. For a long time, I thought stories functioned mostly as an escape from the quotidian responsibilities and minutiae of life. But I don’t know that I believe stories are a way to escape anymore. I’m starting to believe that they are an essential part of life itself—a necessary element that keeps us moving forward.

2. Punch Me Up to the Gods is a tremendously honest memoir about your upbringing, about growing up Black and gay in a working-class family and constantly wishing you were a different person—so much so that you often orchestrated elaborate lies about where you came from, in order to hide yourself. In addition to writing about your life, you’ve also participated in The Moth, a storytelling series where participants share true stories before a live audience. As someone who had a penchant for hiding who you were, when did you realize there was value in your real story? What was it like to reveal your experiences publicly for the first time? Has it gotten easier as time has gone on?

There’s a great quote from the one and only James Baldwin: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

I relate to this quote even though books weren’t what connected me to the fact that the things that tormented me were also the things that connected me to others. No, for me, it was drug and alcohol recovery. By the time I got to rehab, I was exhausted. Not just from booze and drugs, but from all the lies. It’s not easy telling everyone you know that for most of the time they’ve known you, you’ve been a liar. But I truly wanted a clean slate. The reality, though, is that even after awhile, the slate can never be totally clean. I like to get it as close as I can. Those who don’t forgive me for my lies have every right not to, but at least I’ve told the truth now in a document that will live beyond me. Maybe others who feel shame about who they are and where they come from will find it and know that lying to ensure everyone else’s comfort is not the way to go. Maybe my truth will encourage someone else’s truth.

Now I’m trying to tell the truth every chance I get. Storytelling in front of an audience has become a big part of that. I didn’t expect it to. After I got out of rehab, I told my recovery story on stage at The Moth and was genuinely surprised that I didn’t get booed. People clapped and cheered at the truth. Imagine that. After I had been avoiding it for so long. I felt a bit of a weight lifted off my shoulders that night, so I’ve tried to continue on in that vein. It hasn’t gotten easier. I don’t know that it ever will. But I know that, afterward, I feel a bit more unburdened by who I used to be.

“We need stories to show us the way—to give us guidance. Just as importantly, stories can feel almost like human contact, or at least connection—something I think a lot of us have been missing lately. After all, the power of narrative often lies in what we see in its characters and what we hope to see in ourselves.”

3. Another theme that is pretty consistent throughout Punch Me Up to the Gods is that of buses and public transportation. You seem to spend a great deal of time on buses, in between places—interacting with people you normally wouldn’t, thinking (often anxiously) about what’s waiting for you at home, dreaming of faraway places. Out of habit, do you still do a lot of thinking, or writing, on the go?

I think I’m probably one of six people in the world who actually enjoys riding the bus. There’s a vibrancy there where I feel like I’m socializing, but I’m not really socializing. I don’t actually interact with people so much as I spy on them. I used to write a daily story about my adventures on the P1, a bus that I ride every day in Pittsburgh. The P1 is interesting because it covers a lot of neighborhoods in the city and different kinds of people are boarding and alighting, and I eavesdrop on their conversations—both in person and on the phone. If you’re going to write nonfiction, the bus is a great place to gather little mini stories. I take out my pen and pad and just scribble notes about what I see and hear. It will be a sad day for me when I actually have to start driving places.

These days, I really do like being at home more. But I realize that the stories are out there in the world. So sometimes I get on the bus when I don’t even really have anywhere in particular that I want to go. Sometimes I’ll invent an errand just to get on the bus and be around people and hear their stories. I think that for the first time in my life, I’m more interested in other people than I am in myself, which is an odd thing to say for a person who just wrote a memoir.

4. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

This is a great question, and I’m going to cheat by naming three. They’re all different, and I love them for different reasons. City of Asylum is a bookstore on Pittsburgh’s North Side. They provide sanctuary to endangered writers from all over the world so that they can continue writing. By “sanctuary,” I mean that they actually give these writers a place to live so that they can continue their work. For instance, one of their writers in residence has been the target of fundamentalist groups in Bangladesh and has been in residence since 2016. City of Asylum has also welcomed me for readings of some of my early works. It feels like going home when I go there, and they always have interesting events on their calendar.

White Whale Bookstore, also in Pittsburgh, is a small, family-run store that does a lot of work to promote local writers. The owners are warm and welcoming, and it just feels good to go there. The space is small and feels intimate, and I like just wandering around in there. Whoever is working is always ready to talk about writing and books. White Whale is an example of the kind of bookstore that seems to be disappearing.

Finally, I love the Carnegie Library in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh. It’s a place that’s comforting in the way that libraries often are, and upon entry, it feels like you’ve just walked into someone’s living room—someone who loves books. There’s a little café, and when you go further inside, there’s a full-on atrium where you can sit and read. Once, I was in the atrium when a raucous thunderstorm broke out, and I thought I had died and gone to heaven sitting there reading, while the rain and wind battered the windows. But my favorite part of the Carnegie in Oakland is the back section. It’s a labyrinth of shelves that hid little cubbyholes where you can sit and no one can see you. I love going there. Have I told you enough about places to read in Pittsburgh yet?

“Books weren’t what connected me to the fact that the things that tormented me were also the things that connected me to others. No, for me, it was drug and alcohol recovery. . . It’s not easy telling everyone you know that for most of the time they’ve known you, you’ve been a liar. But I truly wanted a clean slate. The reality, though, is that even after awhile, the slate can never be totally clean. . . Now I’m trying to tell the truth every chance I get. Storytelling in front of an audience has become a big part of that.”

5. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

We had a copy of Grimms’ Fairy Tales in my childhood home. The story called “The Six Swans” gripped me and wouldn’t let me go. I read it over and over. It’s about a princess whose brothers are cursed by a witch and turned into swans, and they can’t be turned back unless the princess knits them sweaters made out of nettles and she also can’t speak for six years.

I remember there being so many specific details and plot points. I also remember how vividly the tale was rendered. I felt like I wanted to be a part of the story. What affected me most of all was that there wasn’t a “happy” ending. Happy endings generally rub me the wrong way, even today. I don’t want to give it away, but by the end of “The Six Swans,” all is not well. All is not terrible, but it’s not well either. I prefer those kinds of endings. I’m a firm believer that no end of any story is really “happy,” just complicated—like life itself.

6. If you had to do something differently as a child or teenager to become a better writer as an adult, what would you do?

When I was a kid, my sister gave me a diary that she didn’t want. It was pink, and it had a little ceramic rose on the top left corner. I don’t know what prompted her to give it to me as opposed to just throwing it somewhere and never using it. But she gave it to me, and to this day, I think it’s the most thoughtful gift I’ve ever received. I started writing in it immediately.

Then, my cousin Vince saw me writing in it and told me that I should stop because the act of writing in it was “faggy.” I remember how that word stung. He said it with so much bile. So I decided to change things up because I thought he was referring to the pinkness and the ceramic flower. I started writing in regular notebooks, but that didn’t change anything. Other children told me that it was “weird,” and the weirdness they referred to all seemed to come from a specific place. This thing I was doing was not what boys should be doing. Only girls wrote their feelings down on paper because only girls were supposed to have feelings. So I stopped writing for a long time. I kept the occasional journal, but the old feeling of shame would eventually rear its head and I would stop.

What I would do differently would be to tell my cousin to mind his own business. I would tell the other kids who made fun of me to kick rocks. I would just continue to write. I think about it often, actually. Who knows what kind of writing the person I used to be could have produced? It could have been terrible or it could have been brilliant, but I’ll never know. In the end though, I truly believe that I would be a better writer today if I had just kept it up and made the mistakes that are necessary to become a better writer when I was young.

7. Something I noticed as I was reading the book was your capacity for empathy—for yourself, for your parents, and for people that didn’t necessarily deserve it. As a nonfiction writer, how do you write about people in a way that feels nuanced, that factors in resentment, love, jealousy, or all the above?

7. Something I noticed as I was reading the book was your capacity for empathy—for yourself, for your parents, and for people that didn’t necessarily deserve it. As a nonfiction writer, how do you write about people in a way that feels nuanced, that factors in resentment, love, jealousy, or all the above?

When I look back on my life, I realize that I did not always behave in a noble way. I stop short of saying that I was a “bad” person, but I did do bad things. When I think about those things, I know that there was a reason in doing them. Not always a good reason, but a reason, nonetheless.

I went through the normal process in AA of apologizing to specific people for my behavior. Some of them forgave me, and some of them didn’t. I found myself engaging in a kind of self-torture for those who didn’t. I recognized that no one has to forgive me. But I had a difficult time forgiving myself, and that did me no good. So I’ve been trying to forgive myself for stealing and lying and being an all-around asshole. And when I wrote the characters in the book, I found myself trying to afford them the same grace.

Right now, with social media and so many people’s mistakes being on public display, we’ve entered into a good/evil phase where we judge people with no nuance at all. It’s so simplistic. Marvel stories have a clear hero and a clear villain, and that’s great for superhero stories. But that’s not real life. I think the real villains in the book are faceless. The villains in the book are the ideas that are so entrenched in our culture. Sometimes, people promote these ideas because they don’t know any better. But I wanted to give the people in the book the chance to be human beings. Some will read and still cast people as villains or heroes. But that’s not really how life works, in my opinion.

“Marvel stories have a clear hero and a clear villain, and that’s great for superhero stories. But that’s not real life. I think the real villains in the book are faceless. The villains in the book are the ideas that are so entrenched in our culture. Sometimes, people promote these ideas because they don’t know any better. But I wanted to give the people in the book the chance to be human beings.”

8. What was one of the most surprising things you learned while writing your book?

The thing that surprised me most was that some of the most giant moments in my life really didn’t even make a blip on the radar of the other people involved. Things that meant the world to me barely resonated with the person or people who were with me. This also happens in reverse. My sister just told me about something that happened when we were children that had an enormous impact on her, but I don’t remember it at all.

I hadn’t considered that the most important moments in our lives are often just moments we have by ourselves. It’s comforting to me to know this. All around you every day, people are experiencing watershed moments that don’t involve you at all. It makes me feel alone, but in a good way—alone but not lonely. The shared experience of everyone having these moments should assure us that there is no one else in the world living the exact same life as we are. That’s huge to me. And while we may have some experiences in common, there is no person out of seven-and-a-half billion who is experiencing the exact same thing.

9. Two storylines accompany your own throughout the book: that of the narrator in Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “We Real Cool,” and that of Tuan, a young Black boy you encounter on the bus—one whose innocence reminds you of your own from childhood. Did you always plan to frame your story with theirs?

I didn’t plan it. Those elements were added later. I was simply writing stories about my life when I discovered the Gwendolyn Brooks poem. It felt like she read my mind 10 years before I was born. After I read the poem, I immediately thought that it was a mini treatise on Black masculinity. I found some interviews with her online, and in none of them does she say the word “masculinity.” But I immediately connected her words to that concept. The stories that I was writing seemed to plug in to each line of her poem, and I just went with it. I also want to be clear that I’m not the first person to see this connection. bell hooks saw it back in 2004 with her book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity. It’s important to note that. Her book is academic and intellectually challenging. I just wanted to use the poem to help frame stories about my life.

The young boy in the book also came about as a surprise while I was writing. I tend to write on the bus a lot, and one day there they were—Tuan and his father. They were acting out exactly the kinds of things that I was writing about. I got my notebook out and started scribbling away about their every interaction and the things that were happening on the bus in general. I hope that the boy and his father are well.

10. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I write about James Baldwin in the book. I admire his writing, but even more, I admire the way he lived. I have made him a hero, invincible in my mind, but that can’t be true. He couldn’t have been invincible. I entertain daydreams of him showing me around Paris and St. Paul de Vence, where he lived. I would love for him to sit with me and just talk about his life, triumphs, and heartbreaks. Maybe some of his triumphs were, in fact, heartbreaks and vice versa.

I’d love to have an elegant meal with him. Fried chicken and collard greens served up on the finest Portuguese earthenware, sweet red Kool-Aid poured into cut glass crystal. I’d love to talk about men with him and how difficult they are to love sometimes. And finally, over sweet potato pie with Cool Whip (a pie that I baked myself), we’d gossip about Marlon Brando and whether or not the rumors were true. A dignified yet ratchet evening kiki’ing with James Baldwin is something I imagine I’ll be treated to in heaven after I die.

Brian Broome, a poet and screenwriter, is the K. Leroy Irvis Fellow and instructor in The Writing Program at the University of Pittsburgh. He has been a finalist in The Moth’s storytelling competition and won the grand prize in Carnegie Mellon University’s Martin Luther King Jr. Writing Awards. He also won a Robert L. Vann Media Award from the Pittsburgh Black Media Federation for journalism in 2019. He lives in Pittsburgh with a cat.