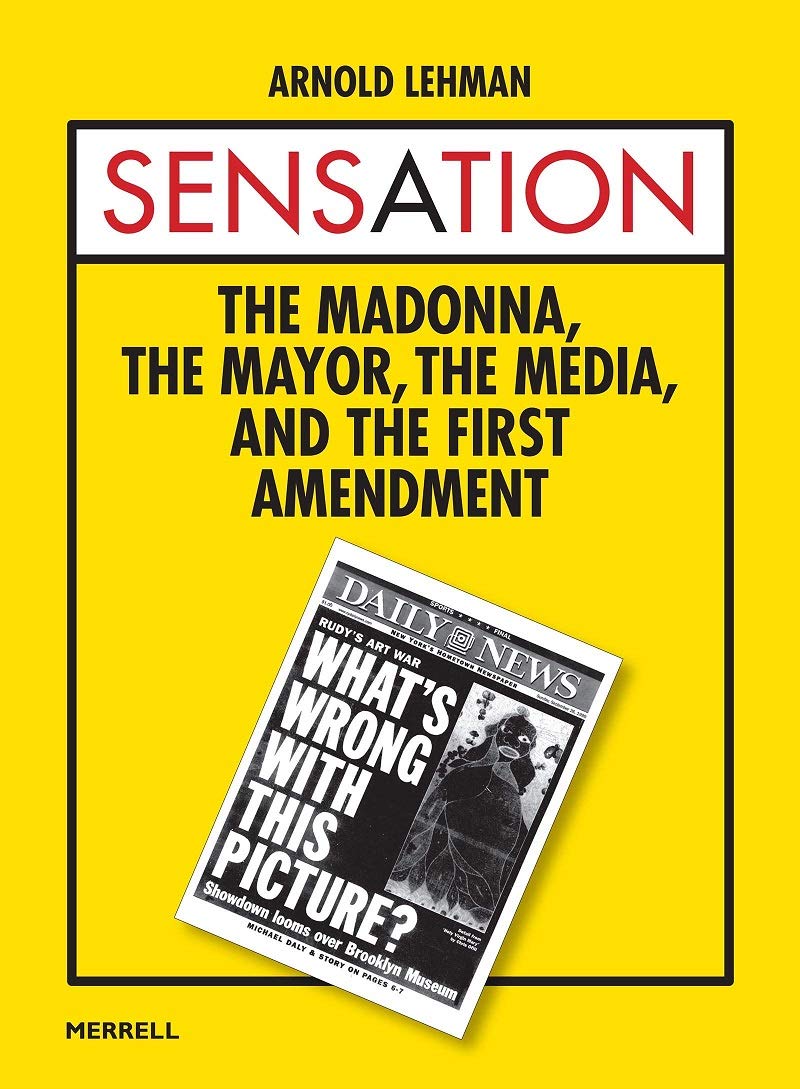

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Julie Trébault speaks with Arnold Lehman, author of Sensation: The Madonna, The Mayor, The Media, and the First Amendment (Merrell Publishers, 2021) – Amazon, Bookshop.

1. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

1. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I spent a year understanding how powerful the written word can be, while in a master’s degree program in the writing seminars at Johns Hopkins University. I wrote poetry for that year and learned that every word I put on paper mattered.

2. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

Self-censorship! Whether it is in our own approach to the written word, or in museum exhibition programming, or in the theater, we are reacting to the volatile nature of our community discourse. Fortunately, the only time my own devotion to free expression has been challenged was during Sensation.

“Whether it is in our own approach to the written word, or in museum exhibition programming, or in the theater, we are reacting to the volatile nature of our community discourse. Fortunately, the only time my own devotion to free expression has been challenged was during Sensation.”

3. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process, and how did you overcome it?

I vividly remember teachers in high school telling me that my writing was excellent but overly long in every context. My response was to more carefully select my words, which I continue to do every day.

4. What advice would you give to a writer who is trying to publish their book—not just in general, but especially in this current climate?

Make certain the writing comes from both the brain and the heart.

5. The public, much like the media, had a multitude of reactions to Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection (1999–2000). How did you hope visitors would react to the exhibit? Did any reactions surprise you?

The vast majority of our 175,000 visitors responded as we anticipated. They were amazed, intensely curious, moved often to tears—slightly shocked. Many closely associated with certain works, and others were repelled.

Most younger visitors were enthralled—many older visitors had to work hard to determine what the artists were attempting to share. Other visitors were annoyed by what they had seen. No one left the exhibition without a sense that artists saw the world often very differently than they do.

“The vast majority of our 175,000 visitors [to Sensation] responded as we anticipated. They were amazed, intensely curious, moved often to tears—slightly shocked. . . . No one left the exhibition without a sense that artists saw the world often very differently than they do.”

6. One of the throughlines in this book is the role of the media in drumming up and adding various voices amid the controversy. How did you remain committed to the exhibition and the myriad tasks at hand with a nonstop media frenzy focused on both the museum and the exhibition?

Other than its security and protection, I had little time to think about the art during the media storm encompassing the exhibition and pointed even more negatively at general museum practice. During much of Sensation, holding together our superb and devoted staff, maintaining a dialogue with our dedicated trustees and donors, working constantly to provide the information needed by the museum’s attorneys, and trying to be honest and responsive to the media was all-consuming 24/7!

7. Other arts institutions and leaders were in a precarious position between wanting to extend support and also feeling threatened by the city’s leadership. How did you navigate this dichotomy, including the fear that you had perhaps “created problems for others in the still rigorously straitlaced American museum community?”

As often as physically possible, I personally communicated with colleagues and friends within the museum community, as well as a few members of the media, to underscore what was actually happening and to correct misinformation that appeared in much of the press. I worked with museum leaders in New York and throughout the country to help in producing letters to the editor, particularly to The New York Times, that were never printed but that contained clear information about museum practices that contradicted what was being published in the press.

8. Chris Ofili’s rendition of the Virgin Mary drew particular attention from every stakeholder in the exhibition’s controversy. You wrote that Ofili’s use of elephant dung in his painting, “is not a story of blasphemy, but of reverence. . . but it is in a language that is foreign to many of us raised in the tradition of Western culture and religious observance. Having traditional African sacred objects in our museums teaches us lessons of tolerance, understanding, and diversity. If people do not make the effort to understand, if people do not exercise tolerance and mutual respect, then we all suffer.” What did this specific painting, and the misunderstanding and criticism it drew, represent for diversity and representation in revered American arts institutions?

8. Chris Ofili’s rendition of the Virgin Mary drew particular attention from every stakeholder in the exhibition’s controversy. You wrote that Ofili’s use of elephant dung in his painting, “is not a story of blasphemy, but of reverence. . . but it is in a language that is foreign to many of us raised in the tradition of Western culture and religious observance. Having traditional African sacred objects in our museums teaches us lessons of tolerance, understanding, and diversity. If people do not make the effort to understand, if people do not exercise tolerance and mutual respect, then we all suffer.” What did this specific painting, and the misunderstanding and criticism it drew, represent for diversity and representation in revered American arts institutions?

“The Holy Virgin Mary” by Chris Ofili explosively defined the lines for those of us whose vision does not go beyond the edges of Western culture. The lessons that should have stimulated even the most modest understanding of issues related to diverse peoples and practices, which I had thought many of us—at least those in urban centers—learned from our school trips to museums had not prepared many who were confronted with a Black Madonna.

Even those of us who actively shared a religion and its visual manifestations were unable or unwilling to step beyond 1,000 years of the white Virgin Mary as depicted in almost every American art museum. This barrier does not even begin to address the issue of purported pornographic images surrounding the Black Mary as though miniscule putti.

“I do believe that American museums continue to present exhibitions and programs that approach and challenge the status quo.”

9. You write that “museums are safe places for unsafe ideas.” In your opinion, how are museums today continuing to challenge the public’s ideas? Which new challenges, if any, prevent museums from living up to this ideal?

I do believe that American museums continue to present exhibitions and programs that approach and challenge the status quo. I’ve recently been fascinated with the current exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse, which melds the recognition of visual arts and music of Black Southern artists in a new and exciting manner.

I was similarly emotionally engaged and sometimes enraged by the astonishing revelations unveiled by artist Titus Kaphar in his exhibition Shifting the Gaze at the Brooklyn Museum in 2019. And for some reason, Kaphar’s exhibition reminded me of another exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum two decades earlier in 2000, Hip-Hop Nation: Roots, Rhymes and Rage, which provided extraordinary insight into the ways in which young people—especially young people of color—were communicating, again through the visual arts and music.

However, for many in the white community, it remained an unknown and even destructive language. Some in the media suggested that it was inappropriate for an art museum. Clearly, there was no understanding that “museums should be safe places for sometimes unsafe ideas!” Museums, just as every other cultural and educational institution that struggles with the presentation of ideas, must have strong and thoughtful trustee and community leadership.

10. Twenty-two years after the infamous lawsuit, the Brooklyn Museum continues to be a leader in protecting freedom of expression. Seeing the legacy your tenure and Sensation have left on the institution, what would you tell your pre-Sensation self?

That is the easiest of questions to answer because there is only one answer that counts. Do what is right.

A bold and progressive museum director for over 40 years, Arnold Lehman has always advocated for freedom of expression, diversity, social justice, and accessibility. Under his guidance as director, over 500 exhibitions were presented at the Brooklyn Museum and, earlier, at the Baltimore Museum of Art. He served in major cultural leadership roles nationally and in New York City throughout his distinguished career. He received his MA from Johns Hopkins University, his M.Phil. and Ph.D. from Yale University, and his DHL from Pratt Institute. Lehman was a Ford Foundation Fellow and currently serves on numerous nonprofit boards focused on culture, education, and social justice. He chaired the board of Legg Mason, where he served as a director for 40 years, and is currently a trustee of funds in the Franklin Templeton complex. Since 2015, he has been a senior advisor at Phillips.